This article first appeared on The Conversation.

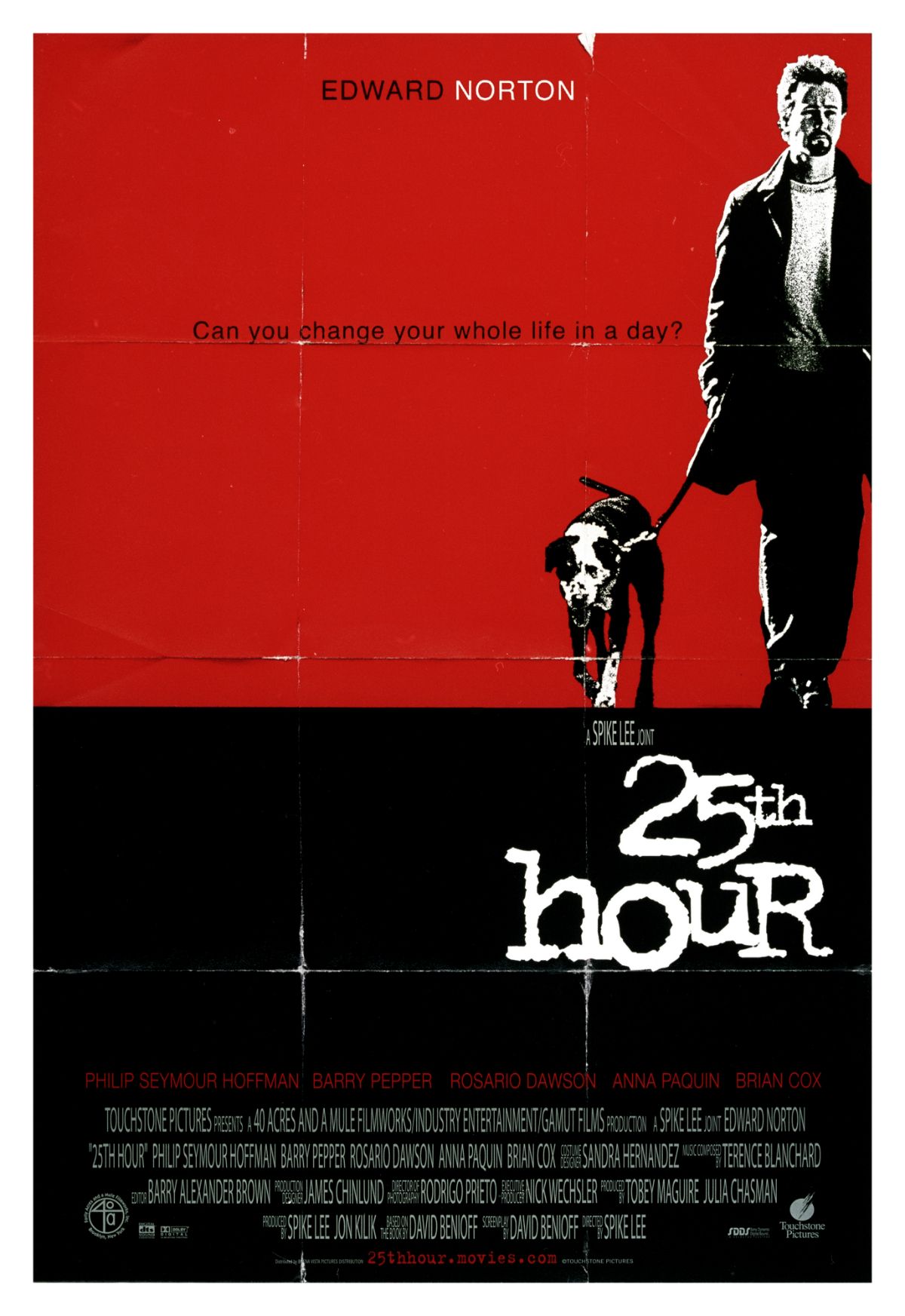

The most enduring cinematic representation of 9/11 was not originally meant to be about the World Trade Center attacks at all. Spike Lee's 25th Hour, released in 2002, was mostly shot during the summer of 2001 and was reworked following 9/11. In fact, while blockbusters such as Spider-Man (2002) were hastily re-edited to remove images of the World Trade Center, Lee made the attacks fundamental to 25th Hour, building in extended shots of Ground Zero and the Tribute in Light to pivotal moments in the film.

Unlike some high-profile releases—such as Oliver Stone's World Trade Center or Paul Greengrass's United 93, both released in 2006—Spike Lee's 25th Hour manages to capture the post-9/11 lassitude that was so acutely felt by Americans, while simultaneously delivering a trenchant political critique.

The film's main character, Monty (Edward Norton), is a convicted drug dealer who has just been sentenced to seven years in jail. The narrative follows his final day of freedom: His world has changed irrevocably and he is suspicious of everyone.

25th Hour is worthy of reappraisal for many reasons, but I'd like to focus on how it handles an increasingly vexing aporia—the problem of meaningfully addressing the impact of 9/11 without reinforcing the notion that the attacks came "out of the blue" or "changed everything." These conceits have proven problematic as they tend to remove the attacks from their contexts, pre-histories and effects and have been used ideologically, to advance unilateral agendas—and a stubborn brand of American exceptionalism.

Cinema, literature, art, commentary and scholarship—even work that critiques such notions—have often inadvertently perpetuated this idea of exceptionalism simply by placing yet more attention on 9/11. This practice of attaching too much singular importance to the attacks is easy to identify in retrospect, but was harder in the earlier aftermath.

Additionally, filmmakers faced more immediate challenges in depicting 9/11. That the attacks were seen as profoundly "cinematic," for example. Cultural theorist Slavoj Zizek famously wrote that the oft-repeated television images were "reminiscent of spectacular shots in catastrophe movies," or "special effect[s] which outdid all others." So there was a practical problem of filming something already seen as cinematic, but also an unsettling and traumatic intersection between reality and fiction.

A further challenge for filmmakers has been locating a political position, given the context of the highly divisive War on Terror. The convergence of these issues partially explains the inward approaches of Stone and Greengrass—two of Hollywood's most political directors. Both World Trade Center and United 93 focused on the immediate emergencies of 9/11 and opted to ignore the associated geopolitics.

Without wider contexts, their "micro" approaches perpetuated this inward drift and chimed with other trends: A need for masculine heroes, commemoration, memorialization and the need to work through trauma. They also spoke to a burgeoning nationalism and xenophobia, as I've argued elsewhere.

'25th Hour' as national allegory

In one striking scene in 25th Hour, Monty's friends Francis (Barry Pepper) and Jacob (Philip Seymour Hoffman) discuss his fate while looking down at the floodlit excavation of Ground Zero. As they outline his grim destiny, the camera pans menacingly down to the site of destruction, binding Monty's story to the story of 9/11.

This depiction of Monty is perhaps most suggestive in one of two stylized set pieces in the film: the "Fuck You" monologue. Monty stares into a bathroom mirror, seeing in the image of himself, New York's diverse multitudes—as well as his friends, father, partner, Osama bin Laden, George Bush and Dick Cheney—and he rants viciously at them all.

This scene takes on its full significance when Monty finally accepts blame. Staring at his allegorical self in the mirror he concludes: "No, fuck you, Montgomery Brogan—you had it all and you threw it away."

As film scholar Guy Westwell has noted, 25th Hour shows how "activities in the past have played a role in shaping the circumstances of the present." In other words, as Monty recognizes his own culpability in his downfall, there is a bold (particularly for 2002) suggestion that America too, can look to its own actions for answers.

25th Hour's allegory is strengthened in its second set piece, a fantasy sequence where Monty imagines going on the run rather than reporting to Otisville Prison. In his imagination he heads west in his father's Jeep Grand Wagoneer, American flag flying. His father (Brian Cox) provides the voiceover narration, evoking national origin myths: "We drive west, keep driving until we find a nice little town. These towns out in the desert—you know how they got there? People wanted to get away from something else."

In his vision of an alternate future, Monty gets a job, marries his Puerto Rican partner Naturalle (Rosario Dawson) and has a large inter-ethnic family—who are all shown dressed in immaculate (and symbolic) white. This nostalgic evocation of national origin myths, a prevalent post-9/11 trope, is then exposed as the fantasy collapses.

National trauma

25th Hour critiques a culture of suspicion, urges self-reflection, challenges the nostalgic turn and recourse to crassly gendered national origin myths. But it also affectingly captures the melancholic and traumatized national mood after the attacks.

There are other valuable 9/11 films that sensitively deal with national trauma while offering political insight. Alain Brigand's assemblage of short films titled 11.09.01 (2002), is designed to look at 9/11 from a global perspective. Ken Loach's contribution, which tells the story of the "other 9/11"—the Chilean coup d'état of September 11, 1973—is exemplary.

Bryan Appleyard has argued compellingly for Man on Wire (2008) as the "most important" 9/11 film. For Appleyard, James Marsh's documentary account of Philippe Petit's tightrope walk between the towers in 1974—precisely by not mentioning the towers—affects an "anticipatory sadness and nostalgia for a pre-9/11 world."

For me, though, 25th Hour deals with the loss and trauma of 9/11 while also examining, unflinchingly, the inwardness and isolationism of post-9/11 America.

Arin Keeble is lecturer in contemporary literature and culture at Edinburgh Napier University.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.