On May 14, 1942, Michael Yanoscik went down Washington Street one last time. He grew up at 9 Albany Street, where today there is a W hotel looking down at the twin cataracts of the 9/11 Memorial. The neighborhood, when Yanoscik lived there, was called Little Syria or the Syrian Quarter. Though named for its sizeable Syrian and Lebanese population, this tenebrous sliver of lower Manhattan was packed with Irish, Armenians, Jews, Palestinians, Greeks and Slovaks like Yanoscik.

Yanoscik left lower Manhattan to fight in World War II. He did not come back, becoming the first soldier from Little Syria to perish in the conflict. And so they carried his casket in a parade, from his home, past the St. Joseph's Maronite Church at 57-59 Washington Street toward the St. Nicholas Orthodox Church on East 10th Street in the East Village. The latter church remains; the former is gone.

The memorial service for Yanoscik was organized, according to the book The Financial District's Lost Neighborhood: 1900-1970, by a Lebanese dock-worker named Azeez Najar, an Irish police officer named James Cox and a Polish barkeep named Joseph Radnov. They were all residents of what was the first settlement of Arabs in the United States. Today, Little Syria is close to gone and just as close to forgotten, slipping ever deeper into obscurity with each passing year. The new 9/11 Museum, part of whose aim is to tell the history of lower Manhattan, pretends it never existed, maybe because mentioning Arabs in any context outside of We have some planes might discomfit patriots with no patience for nuance.

If there was ever an Arab Street in the United States, then Yanoscik lived there: not the furious Arab Street burning the effigy of George W. Bush or the Israeli flag, but a byway of American comity and American struggle. By forgetting it, we forget something of ourselves.

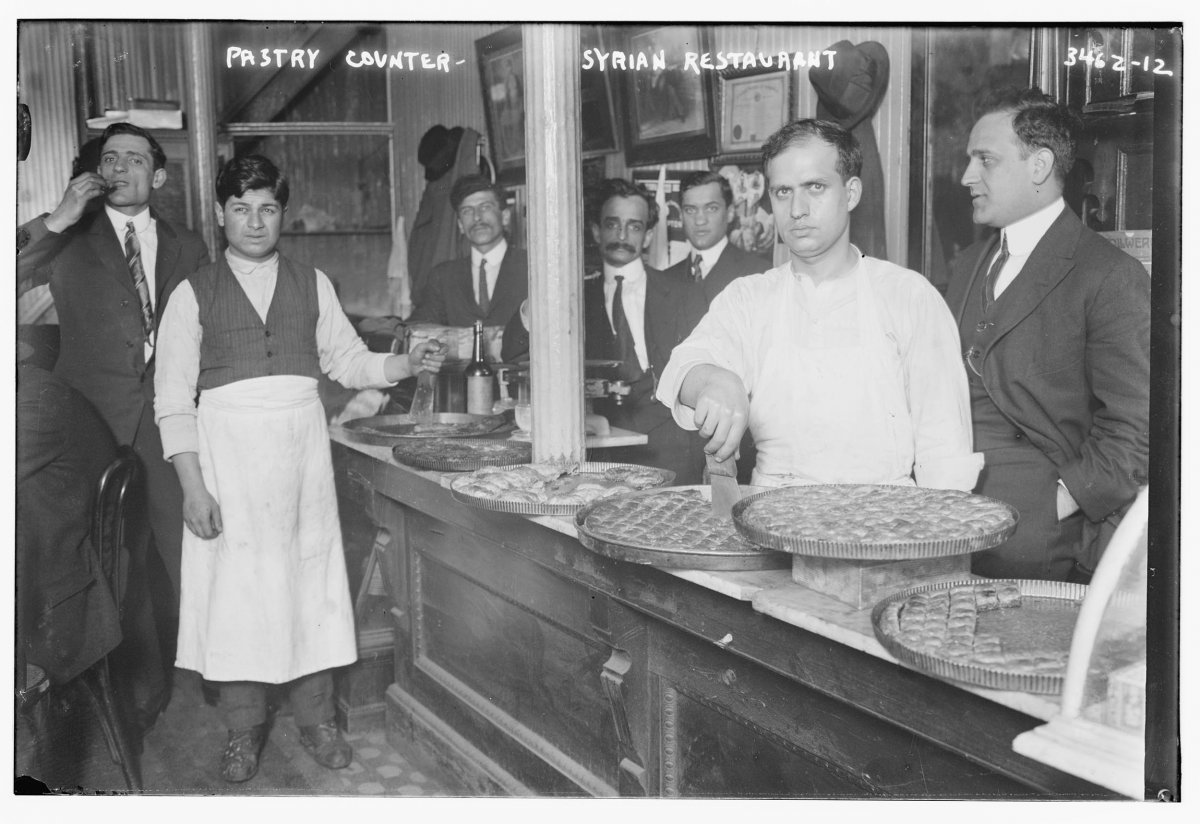

Two hundred years ago, the waterfront on the west side of lower Manhattan was called "Millionaires Row," but by the latter decades of the 19th century, the wealth had moved uptown and immigrants—many of them from the Ottoman Empire—moved in. Here, the store Sahadi Bros. proffered "Oriental" groceries while Markarian Bros. sold the Armenian variety and Gorra's sold Lebanese women's clothing and there was a restaurant called Son of the Sheik at 77 Washington Street, where you could have lunch for 55 cents and dinner for a dime more (no liquor, though). The residents readAl Hoda, the nation's oldest Arab-American daily. They prayed at churches, not mosques, for the Arabs who lived in Little Syria were Christians. So their faith they had in common with their Irish and Slovak neighbors, if little else.

The tropes of the New York immigrant experience constitute a familiar vocabulary of struggle and assimilation: tenements, stickball, fights on humid summer nights, romances conducted over fire escapes. This is the stuff of Call It Sleep, The Godfather, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn. Little Syria belongs to this narrative, but nobody rhapsodizes about Washington Street the way they do about the red-sauce joints of Little Italy or the storefronts of the Lower East Side, where Hebraic lettering is sometimes still visible on dusty glass.

That's partly because there's very little left to see: Only three buildings remain of Little Syria, on a stretch of Washington Street squeezed inauspiciously between Ground Zero and the on-ramps to the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, whose construction in the 1940s destroyed much of the neighborhood. By then, most of the Arabs were gone anyway, having moved to Atlantic Avenue in Brooklyn, which, in places, retains a Middle Eastern feel (Sahadi's, at 187 Atlantic Avenue, is probably the city's premier Middle Eastern grocer). The three plangent edifices that constitute the last of Little Syria sit awkwardly in the shadows of sleek hotels that have sprouted around Ground Zero, glistening mushrooms after a horrible rain.

One of those three buildings is the St. George's Syrian Catholic Church, a gorgeous but grimy terra-cotta structure that was built as a boardinghouse in about 1819 and converted to more exalted use a century later. More recently, it was Moran's Ale House and Grill. Three years ago, that also disappeared. Its current use is unclear. At the very least the building will remain standing, unlike so many others here, for the church received protection from the Landmarks Preservation Commission in 2009. According to the commission's findings, it is the "most vivid reminder of the vanished ethnic community" of Little Syria.

There are two less vivid reminders next to St. George's: the Downtown Community House, with its Buddha reliefs (it was refashioned into the True Buddha Diamond Temple a few years back; this, also, is gone) and a tenement that looks like so many of its red-brick relatives in Chinatown and Little Italy. The former building is empty; the latter is occupied by tenants in rent-controlled apartments, one of whom has posted a sign on the doorway profanely exhorting "yuppies" to have their dogs defecate elsewhere. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has declined to offer protection to these buildings.

That a 19th century immigrant enclave was subsumed by the likes of the Pussycat Lounge (which itself bid adieu to this world in 2011) is just the rapacious way of New York City: Swallow now, regret later. But the opening of the 9/11 Museum earlier this month could have been a moment in the spotlight for a neighborhood that challenges our assumptions of what it means to be an Arab, a New Yorker, an American. Instead, the museum makes no mention of Little Syria. There is, however, a poster from the 1973 film Godzilla vs. Megalon.

Activists have long pressured the museum to include some narrative about the Arabic immigrants who lived in lower Manhattan. They note, persuasively, that a cornerstone of St. Joseph's Maronite Church was found in the rubble of Ground Zero, making it the kind of artifact that could credibly capture the complexity of this area, its evolution from dockside markets to World Trade Center.

Museum director Alice Greenwald said that the cornerstone—which currently resides at the Our Lady of Lebanon Maronite Cathedral in Brooklyn Heights—could possibly be part of a temporary exhibition at some future time, but that it had no place in the permanent collection. Yet if the museum includes a brick from Osama bin Laden's compound in Pakistan, then why not from a house of worship that stood essentially at Ground Zero? The lesson of the Abbottabad brick is simple: We won. The lesson of the cornerstone is both more valuable and more complex: Yes, it comes from an Arab church. And, yes, Arabs once lived here. Maybe not all Arabs are the Arabs you think you know.

It seems plausible that museum officials feared that the mere mention of the neighborhood's Middle Eastern history would spark a facile conflation with Middle Eastern terrorism, and that would in turn cause the kind of row that followed the proposed building of an Islamic cultural center—the so-called Ground Zero mosque—a few blocks north of where the towers stood. Nobody wants to go through that again, with pundits seriously wondering on Fox News if sharia law was coming to the United States. And so the 9/11 Museum has chosen to hush the issue away.

"The historical narrative is broader than what the museum has portrayed," says Peter Gudaitis of New York Disaster Interfaith Services. Much is graceful about the museum, and it excels in capturing the brute tragedy of that cloudless September day. But it shrinks from all but the most simplistic narrative of history, as if complexity were an affront to memory.

There have been plenty of gripes about the 9/11 Museum since it opened: Classicists are upset by a Virgil verse whose martial meaning makes it "shockingly inappropriate," according to one scholar. The pious New York Post fulminated about the museum's "absurd" gift shop; those seeking to purchase an America-shaped cheese tray will now have to look elsewhere. Desperate to find an outrage all of its own, the Daily News discovered that the museum hosted "an alcohol-fueled party night" for benefactors. This is not a happy place, and many are not happy. The Little Syria activists might be unfairly dismissed just another group of naysayers. But their objections are at once quieter and more valid.

Personal memory is allowed to be selective. Collective memory should never be. Yes, many Arabs once lived in lower Manhattan. And then, much later, a few Arabs attacked lower Manhattan. These are both truths. They should not make us uncomfortable.

Correction: An earlier version misspelled the last name of Peter Gudaitis of New York Disaster Interfaith Services.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.