As the band began playing a Latin-style beat, only Sahar Arian's silhouette was visible to TV audiences across Afghanistan. Slumped onstage, microphone in hand, she began singing cloaked in darkness. "Poets only see my body in a poetic way," she sang mournfully, in Persian. "When I bared my soul, they laughed at me."

In late January, millions of Afghans watched Arian's performance on Afghan Star, a wildly popular singing contest modeled on American Idol. As the lights illuminated the 23-year-old singer, one of only two female contestants, it became apparent this wasn't an ordinary performance. It was a protest. Cloaked in a blue burqa, pulled back to show her face, Arian had smeared on dramatic makeup to simulate a beating. Thick streaks of bloody red paint ran underneath her nose, staining her lips and chin. Black smudges around her eyes resembled swollen bruises.

As she rose to her feet to encouraging whistles from the audience, Arian discarded her burqa, belting out original, metaphorical lyrics lamenting Afghan women's lack of value in society. At the end, she fought back tears, as the judges, also visibly moved, rose for a standing ovation.

"I always knew in my heart I would one day shout and scream about this issue," Arian tells Newsweek in an interview at a recording studio in Kabul.

The U.N. estimates 87 percent of Afghan women have experienced physical, sexual or psychological violence, or forced marriage. Most Afghan women live confined by strict patriarchal controls, some even in communities that condone horrific gender-based violence. Challenging that status quo is risky. Female activists and parliamentarians regularly receive death threats. In 2014, Shukria Barakzai, an outspoken member of parliament and women's rights advocate, survived an assassination attempt that killed three others.

Female contestants on Afghan Star are already considered rebellious by many, even if they are dressed in full Islamic clothing. After all, only 15 years ago the Taliban outlawed almost all forms of music and banned women from leaving their homes without a guardian. So when Arian stood alone on the stage that night, her performance was immediately recognized as a remarkable act.

The sole female judge on Afghan Star, popular singer Aryana Sayeed, praised Arian, acknowledging how few are willing to take such a risk. "It was definitely brave of her, as there was a major potential for backlash," Sayeed tells Newsweek.

"I was a small lamb in a wolf's den," Arian says. But, she adds, "I was not afraid."

Arian has a life few Afghan women dream of: She lives in Kabul alone, without family. She grew up in Iran and later Azerbaijan, both countries that generally offer women more social freedoms. But Arian's family retained the conservative values of their homeland, and her father forbade her to studymusic. She snuck out to lessons in secret, learning jazz, pop and opera, but when her father found out, she says, her home became her prison. After six months, she "ran away to Afghanistan to start a music career," she explained.

"The hatred my family have for me because I sing" has been a central source of artistic inspiration, Arian says. "Then I saw what happened to Farkhunda. I wanted to voice both my anger and the anger of all women in Afghanistan."

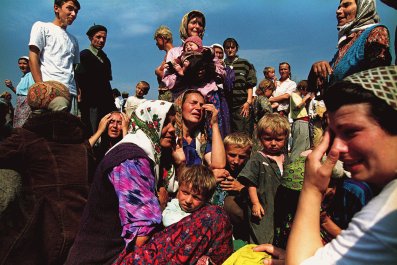

In March 2015, Farkhunda Malikzada, a young Afghan woman falsely accused of burning a Koran, was tormented, tortured and brutally murdered by a mob of men in downtown Kabul. Her sickening ordeal, captured by multiple cellphones, galvanized Afghanistan's women's rights movement. As her innocence came to light, Afghan women exploded in protests of unprecedented size and fury. Thousands gathered, screaming and shouting; they wept and painted their faces blood-red, collectively expressing anger at decades of mistreatment and injustice.

Since Malikzada's murder, Afghan women are daring to protest gender-based violence in ways never before seen in this country. In the past year, before Arian's performance, actress Leena Alam emotionally re-enacted Malikzada's murder in a public play staged near where she was killed. At the funeral, women refused to let men carry Malikzada's coffin, breaking with traditional ceremonial rites.

In November, young women also dominated a demonstration in Kabul to protest the stoning of a woman named Rokhshana. And in a provocative public art performance, Kubra Khademi walked a street wearing body armor with exaggerated breasts and buttocks to protest street harassment.

"I really think the public discussion [about violence against women] is at its peak at the moment," says Samira Hamidi, a veteran women's rights activist. She points to the near-weekly media reports of vicious attacks against women—fathers raping daughters, husbands cutting off wives' noses, stoning attacks—as an indictment of how bad the violence is, as well as a potentially positive development in that women and communities are increasingly reporting these crimes.

"Women are now more aware about where they can go for help and who they can talk to," she says. "Not just women but also the family, neighbors and the community—they are finally talking about it."

International donors have poured millions of dollars into supporting women's rights in Afghanistan, but many young women say they feel little connection to the activists and political elite that are regular fixtures at the multitude of conferences and events on women's rights, often sponsored by Western embassies. "Those women, especially the MPs, they have luxurious lives and can go abroad whenever they want," says Ghazal Aria, an 18-year-old student. "They don't understand me, and I don't think they achieve anything."

Her friend, Mural Sakhi, 21, agrees. "Sahar Arian's performance was something new for us. She sings for the pain of all women," she says. "I haven't joined any protests yet, but Sahar really encouraged me to speak up."

Artistic protests, a very new phenomenon in Afghanistan, "are more powerful and go much further on social and broadcast media," says Ahmad Shuja, a researcher with Human Rights Watch. Performances like Arian's "keep the message alive and help it go farther, reach new constituencies."

Online, Arian's performance went viral, sparking both praise and criticism. Omar Haziri, a 25-year-old shopkeeper, watched the video on YouTube after hearing about it from friends. "It was good she represented the pain and problems of women in our society," Haziri says. "But I'm not sure it was done in a proper Islamic way."

Many other young Afghan men have expressed similar views. Arian was within her rights to raise the issue, many say, but they object to her swaying to the music and to her clothes. (For the record, she wore a floor-length dress, with three-quarter sleeves and a loose black hijab.)

Arian says she received an anonymous, threatening phone call after her performance, but she remains unfazed. "I knew there would be a lot of people against me," she says. "I just want to express women's pain."

She says she is not a political artist, but nevertheless her performance has bolstered the women's rights movement. Afghanistan's problems are so numerous, Hamidi says, that even events as shocking as Malikzada's murder fade easily from public consciousness. "She showed that the movement is ongoing," Hamidi says. "Afghan Star has a lot of viewers, and the judges showed a lot of emotion. People listen to them."

She was voted off the show in late February, failing to make the top five, but Arian says she will continue to sing for women. She has two songs ready for release, both addressing women's rights. "One is called 'Stoning,'" she says. "The other, which is my message to women, is called 'Fly!'"