Inside the Doctors Without Borders hospital in Kunduz, northern Afghanistan, Abdul Ghadir, 43, surveys the overturned bed frames, blackened by flames, and the caved-in ceiling and walls dark with soot. His feet crunch across a floor covered in glass shards and ash. "This," he says, "is the grave of my daughter."

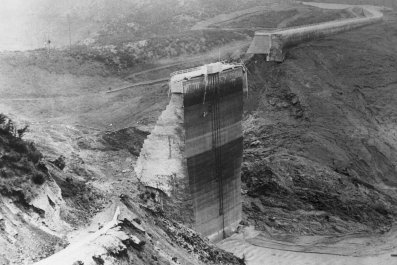

Amina, Ghadir's 12-year-old girl, was killed in the early hours of October 3 last year, six days after the Taliban had captured Kunduz. In support of Afghan security forces trying to take back the city, a U.S. military AC-130 gunship repeatedly fired on the hospital. In total, 42 patients, staff and caregivers were killed, and dozens more wounded, in the hourlong attack. The U.S. has since admitted that firing on the hospital was an error.

Earlier this year, in a crowded room at the Kunduz military base, U.S. military officials apologized to some of the victims and handed out condolence payments. For Amina's death, Ghadir received around $6,000. Those who were wounded received around $3,000.

As the cash was handed out, Ghadir says, he felt desperate and powerless. "The money is obviously not enough compared to the life of my daughter," he says. But he had borrowed money for Amina's funeral, and with a large family to provide for, "I had no other choice but to accept what they gave me."

Two days before the airstrike, a stray bullet hit Amina in the head, and she was rushed to the Doctors Without Borders hospital. After surgery, doctors said they expected a full recovery — Amina would be able to pursue her dreams of becoming a doctor, memorize the Koran and continue studying English at school.

Then the U.S. gunship pummeled the intensive care unit where Amina lay recovering. Like other patients in the ICU, she burned in her bed.

"I took one handful of ash to my wife and said, 'This is your daughter,'" says Ghadir. He couldn't find anything else left of Amina to take.

Condolence payments

Condolence payments are a long-standing U.S. military practice, used in Afghanistan since 2005 to acknowledge civilian harm without admitting moral or legal responsibility. U.N. records show that from 2009 through 2015, at least 21,323 Afghan civilians have been killed and 37,413 wounded. While the U.S. military is responsible for a small fraction of that total, it has never fully disclosed the extent of the harm caused or payments made.

Nevertheless, the limited U.S. military records released under the Freedom of Information Act show a startling catalog of collateral damage, demonstrating the often inconsistent, ad hoc nature of condolence payments. In 2012, a man in Helmand province was paid $972.76 after his wife was killed in an operation by the U.S.-led coalition; in Kunar province, a man received $7,337.61 for his son's death. Because condolence payments are both discretionary and rely on access to the relatives of victims, who often live in insecure areas, some families have likely received nothing at all.

The U.S. military has more than one pot to draw from for the program. The most common source of funds is the Commander's Emergency Response Program. A 2009 CERP manual states that condolence payments are not compensation for loss but "can be paid to express sympathy and to provide urgent humanitarian relief."

For most Kunduz victims, that expression of sympathy has not been enough. Several I spoke to were angry they had not been consulted before receiving just a few thousand dollars. Some referred to much larger payments made in Afghanistan, such as the $50,000 compensation paid for each death caused by Sergeant Robert Bales, who murdered 16 civilians in 2012. They were also frustrated by the lack of transparency.

"Making amends to the victims is about much more than the money," says Marla Keenan, managing director for the Center for Civilians in Conflict, a nonprofit advocacy group. "It can seem incredibly arbitrary if you are the victim and someone shows up on your doorstep with a bag of money."

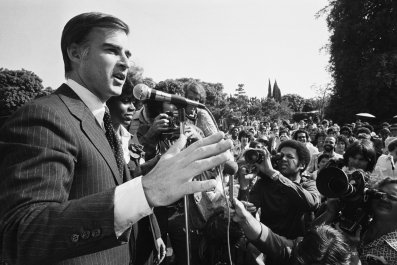

In an effort to address such frustrations, General John Nicholson, the new commander of U.S. forces in Afghanistan, traveled to Kunduz in late March and publicly apologized, asking for forgiveness. Nicholson was accompanied by his wife, Norine MacDonald, who met with hospital staff and victims' families, but the families were disappointed not to meet the general in person.

Keenan praised the personal outreach by Nicholson and MacDonald, but it did little to comfort the victims. Nicholson's apology might have been more welcome had the victims not already felt so insulted. General John Campbell, the American commander at the time of the airstrike, never explicitly apologized or reached out to Doctors Without Borders. "At that time, we really needed to hear from [the U.S. military]," says Enayatullah Hamdard, a representative of the families of the 14 hospital staff killed. "Instead, they come after five, six months, and they didn't meet with the families."

Some Kunduz victims also expressed frustration over how little they knew about the attack. The U.S. has ignored Doctors Without Borders's repeated calls for an independent investigation and has yet to release the results of an official investigation. "I don't know what is going on with the U.S. Army in Afghanistan. On one hand, they are helping the Afghan government; on the other side, they are killing Afghan citizens," says Turailai Salih, a hospital storekeeper who suffered a shrapnel wound. "Why did they do this?"

The victims also say the condolence payments are not adequate to cover what they have lost. "We know that no amount of money can compensate for the tragic loss of life," says Brigadier General Charles Cleveland, the U.S. military deputy communications chief in Afghanistan. The payments, he says, "are an expression of condolences only; they are not compensation."

'You are nothing'

Some Kunduz victims asked for compensation in addition to the condolence payments. In response, U.S. military officers distributed compensation claim forms that Cleveland says will be adjudicated under the Foreign Claims Act (FCA), which allows awards of up to $100,000. That was welcome news to the victims, many of whom lost breadwinners or need long-term medical care.

Zabiullah Niazi, a hospital nurse, was his family's sole provider, earning around $400 a month. His left arm was severed just below the shoulder, his right hand damaged and his left eye permanently blinded by the attack. He received $3,000. Reports often compare the relatively small condolence amounts to Afghanistan's low average wages. This fails to recognize that for skilled professionals like Niazi who support large families, it is a pittance.

Niazi says he accepted the condolence payment only because he believed additional compensation would be paid. His medical expenses alone have so far amounted to $6,000. He is now furious after legal experts from Doctors Without Borders and elsewhere concluded that Kunduz victims are almost certainly ineligible to receive FCA compensation. That is because the FCA pays only when the harm was caused by a noncombat action; for example, a traffic accident, not an airstrike that targeted a hospital in error.

"We realized this form [distributed by the U.S. military] was a legal dead end," says Guilhem Molinie, Afghanistan country director with Doctors Without Borders. "What is this? This is manipulation of people, giving them hope."

Cleveland did not directly address Newsweek 's question about whether the FCA would allow for compensation in this case, saying a determination would be made once a claim was received.

Hina Shamsi, director of the American Civil Liberties Union's National Security Project, says any lawsuit for compensation by the Kunduz victims is unlikely to succeed. "I wouldn't want to rule it out, but the hurdles are very significant," she says. For cases brought by foreign citizens concerning rights violations by the U.S. military abroad, "U.S. courts have a shameful record of dismissing them on jurisdiction or immunity grounds without getting to the merits."

Keenan says the U.S. should adopt a comprehensive standing policy to make amends to all civilian victims wherever incidents occur. "It is absolutely key to address civilian harm in the right way," she says.

Without proper compensation, the Kunduz victims will not be able to move on with their lives, says Molinie. At the hospital, a large fence has been erected to obscure the view of the bombed building at the request of the staff, who could no longer bear to see it. "They know who was killed where in the hospital," he says.

One of those staff members is Salih, the storekeeper. His easy smile disappears as he recalls rushing through the hospital that night, hearing the screams of patients and seeing colleagues die in front of him. Salih brightens, however, as he tells a new joke among his friends in Kunduz: "You are nothing. You just cost $3,000," he says, smiling wryly. "Every Afghan is $3,000 for America. They give you money, and then you can go."