June 2014, and an unusual three-day conference is taking place in the basement room of New York University's School of Law. The 200 or so attendees that have hurried their way across sunny Washington Square include FBI agents, lawyers, auction house heads, art dealers and collectors who buy and sell multi-million--dollar items.

Waiting, sharp-suited, is -Brooklyn-born conference organiser Chris Marinello, arguably the world's most experienced art hunter (£350m's worth recovered so far) and founder-director of London-based Art Recovery International. The conference is titled "Fakes, Forgeries, and Looted and Stolen Art" and these industry bigwigs are here to discuss the vastly underestimated and booming business of art crime. As we take our seats, a lawyer comments that "three days is extremely ambitious to fit all that in".

He's not kidding.

If it seems hard to imagine that art crime is, according to the US Department of Justice and Unesco, the third highest-grossing criminal trade over the past 40 years (just behind drugs and weapons), then consider that the art trade is the largest lawful unregulated business on the planet, leaving hardly any paper trail for detectives to follow. Buying a sculpture or painting is just like acquiring a bicycle from Gumtree or Craigslist. We wouldn't buy a house without a deed, yet people do this with art worth millions of dollars all the time.

There are also no transaction records. There is no legal requirement to publicly list art sales. The only chain of title that exists in art is "provenance", a potted history full of blanks, anomalies and guesswork. In the US, there's one art crime officer for every 21 million people (that's sixteen in total) and New Scotland Yard in the UK has just two-and-a-half officers (one is part time).

Among the speakers at the conference are Bob Goldman and Bonnie Magness-Gardiner, the Mulder and Scully of the FBI, in that they run a tiny, underfunded department (Art Theft) that no one else seems to believe in. Blonde, mustachioed Bob, who left the FBI to become a lawyer for white-collar-crimes, is still passionate about recovering stolen art. He's the first to admit "it's a dismal effort".

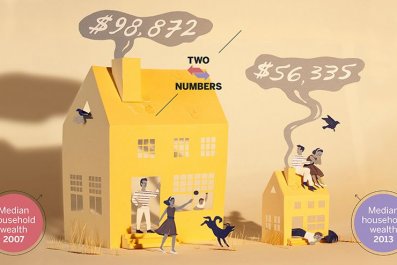

Thanks to lack of regulation accurate figures for the art market as a whole are impossible to ascertain, but Christie's and Sotheby's together turn over about $11-12 billion a year and a 2008 survey by ARTnews, the world's most widely circulated art magazine, estimated that annual private art sales amounted to $30 billion.

The amount of criminal income generated by art crime each year is thought to be $6-8 billion, according to the FBI. In the UK, the value of art and antiques stolen each year is around £300m, second only to drug dealing and more costly than the theft of stolen vehicles. These figures are woefully inaccurate simply because we can't possibly know about every single illegal trade that takes place, with some stolen, looted or forged pieces being sold multiple times. Worldwide, some 50,000-100,000 works of art are stolen each year. Not surprisingly only about 10% of stolen art is recovered, and successful prosecution occurs even less frequently.

CLEAN SWEEPS

Anthony Amore, another former federal agent speaking at the conference, has been head of security at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston since 2006. He is hunting artworks worth $500m stolen from the Gardner in 1990.

A night shift security guard made "the most expensive private security error in history", according to Amore, when he buzzed in two men claiming to be police officers who made off with, among others, Rembrandt's Christ in the Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633) and Vermeer's The Concert (1664).

Milton Esterow, 85 was, for 38 years, the owner of ARTnews, and has -covered countless art crimes. He agrees that poor security fuels thefts. "After the 1911 theft of the Mona Lisa, guards performed an inventory of the Louvre and found another 323 paintings were missing." Magness-Gardiner confirms, shockingly, that this is still a common finding today. In 2012, the Californian city of San Francisco hired an art detective to hunt for hundreds of items that had gone missing from its 4,000-piece public -collection.

The conference room is packed when Chris Marinello takes to the stage with Marianne Rosenberg, the star draw. Rosenberg and Marinello are at the heart of the fight to end the continuing trade in Nazi-looted art and are currently embroiled in what has become the most infamous stolen art case in history. Rosenberg is the granddaughter of Parisian art dealer Paul Rosenberg. From 1911, at his gallery at 21 rue de la Boétie, Paul Rosenberg charmed wealthy French patrons into paying top dollar for the works of Delacroix, Rodin, Cézanne, Manet, Degas, Monet, Renoir, Lautrec, Modigliani, Braque, Matisse and best friend Pablo Picasso, who lived next door. Forced to flee France by the Nazis, who stole the bulk of the Jewish art dealer's world-class collection (400 works), Rosenberg moved to New York. He spent the rest of his life – as did thousands of other Jewish families – hunting for his treasures, originally bought for hundreds of dollars, today worth many millions.

His granddaughter is still trying to track down the 60-odd missing paintings that remain and has recently recovered, with the aid of Marinello, Monet's Waterlillies (1904) and Matisse's Woman in Blue in Front of a Fireplace (1937) from two separate museums, both of which had to be cajoled into giving them up even after being presented with irrefutable evidence, including papers signed by Herman Goering, claiming the Matisse for the Reich.

The case that everyone has come to hear about today, however, is that of 81-year-old Munich-based hermit, Cornelius Gurlitt, son of Nazi art dealer Hildebrand Gurlitt.

Starting in 1938, Hildebrand purged what the Nazis termed "degenerate art" (almost all modern art) from German state collections and bought works, mainly old masters, for the Führermuseum, to be built in Hitler's adopted hometown of Linz, Austria.

The campaign quickly became one of confiscation as the focus shifted to the galleries and homes of Jewish collectors.

Interviewed by the Monuments Men at war's end, Hildebrand Gurlitt convinced them that he'd handed over all he had. The truth was rather different. After the war, he joined other former Nazi-collaborating art historians, dealers and museum heads in Munich, where they conspired to create a market, using a Swiss-Liechtenstein network, for their looted artworks, which is still operating today.

Hildebrand Gurlitt died in a car crash in 1956 but Cornelius continued to sell from the hoard. Questioned by customs on a train from Zurich to Munich in September 2010, unemployed Gurlitt was found to have €9,000 in crisp €500 notes from a Swiss art dealer. An investigation was launched and customs officials found 1,280 Picassos, Chagalls and Gauguins, amongst others, worth at least $1billion, packed into Gurlitt's otherwise modest Munich apartment.

Incredibly, the trove was an open secret among some art dealers. Speaking to Professor Jonathan Petropoulos, author of The Faustian Bargain: The Art World in Nazi Germany, an unnamed dealer said: "In Munich art-dealing circles one knew that the Gurlitt family had [or "disposed over"] an extensive collection of art." The full list has not been made public. But one of the most valuable paintings in the trove has been revealed: Matisse's Seated Woman/Woman Sitting in Armchair (1921), stolen from a bank vault rented by Paul Rosenberg by the Nazis on September 5th 1941.

Rosenberg and Marinello immediately submitted a detailed claim to the German government. "I also wrote to Gurlitt directly," Marinello said. "He offered to sell us the Matisse." The answer was No. Gurlitt then suggested auctioning the work, offering a 50/50 split. "Our one and only offer was of unconditional restitution," Marinello said. "We do not negotiate because it creates a horrible precedent," Marianne Rosenberg confirmed.

Gurlitt agreed, eventually. Marinello was within hours of collecting the painting when Gurlitt sacked his lawyer. During the delay this caused, a false claim was made for the same painting. Three weeks later, on May 5th, 2014, Marinello was again within a hair's breadth of recovering the Matisse when Gurlitt died.

CRIME AND RESTITUTION

On June 12th 2014, Ingeborg Berggreen-Merkel, head of the committee charged with establishing the provenance of the Gurlitt trove said they agreed that Matisse's Seated Woman/Woman Sitting in Armchair is "Nazi-looted art that legally belongs to the Paul Rosenberg collection".

Great news. Except for one thing. Even though Gurlitt signed an agreement with the German government stating that works determined to have been looted must be returned to the victims' descendants, he willed his collection to the Kunstmuseum in Bern, Switzerland, which is at the moment deciding whether to accept.

Although Marianne Rosenberg and her family (her 90-something-year-old mother is still alive) will have to wait a while longer, they shouldn't have to. The Washington Principles, signed by 44 nations in 1998 and reaffirmed by 47 nations in 2009, state that Nazi-confiscated art must be identified, that all relevant records and archives be accessible on a central registry and that art being sold with second world war provenance gaps must be given extra consideration.

After all, as US officials put it, thousands of American soldiers had given their lives to make sure all of Hitler's depredations were undone. Not returning the art was like helping the Nazis.

None of these aims have been universally achieved. For example, May 29th this year was the first time any German art dealer made its records from the Nazi era public when the Neumeister auction house (known as Weinmüller's before the war) put the list of stolen pieces online (lostart.de).

Weinmüller sold a total of 32,000 Nazi-looted works of art between 1936 and 1944 and held a further 35 auctions before his death in 1958. The list (discovered by chance in an air conditioning cabinet in March 2013) is almost three times as long as Hildebrand Gurlitt's. The unregulated nature of the art business makes looted and stolen works easy to sell, their true provenance unnoticed, time and again.

The outspoken, elderly American dealer Richard Feigen opened his first gallery in 1957, exhibiting German expressionist and surrealist art. Feigen is one of many dealers at the New York conference who makes the point that too many people in the art world simply "look the other way".

Esterow agrees. "Some dealers are not operating illegally but without ethics," he says. "How much truth there is in that statement, we're still trying to find out. Many art sales are made privately and galleries don't talk about them."

The temptation is for dealers to turn a sale around quickly for a large commission/profit. "The art market is going insane," Esterow says. "Prices are berserk ... Five years ago Forbes listed 900 billionaires in the world. This year it's 1,346. Instead of buying houses, horses or a slew of girlfriends they are buying art."

Recent private sales include Gustav Klimt's Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer (1907) for $135m; Willem de Kooning's 1955 Police Gazette (bought by hedge fund manager Steve Cohen) for $63.5m (Cohen also bought van Gogh's Peasant Woman Against a Background of Wheat (1890) and Gauguin's Bathers (1902) – for about $120m in 2005); Jasper Johns's False Start (1959) sold to hedge fund operator, Kenneth Griffin, for $80m (the public-auction record for Johns is $17.4m.)

Jane Jacob, art historian, provenance research Expert and president of Jacob Fine Art, is co-organiser of the conference on stolen art. "Some [investors] want to turn things around in two weeks which is impossible," she says. "Due diligence often takes months."

Should there be a licensing regime for dealers along with a code of conduct and regulators? The dealers at the New York conference are prepared to consider it, but no one is sure how this might be achieved. "Nothing's all that effective right now," Feigen says. "I saw a painting with poor war provenance vetted out of the Maastricht art fair, so the dealer sold it privately for a fortune. There's a lack of communication across the industry."

That lack of communication and commitment to the Washington Principles extends to museums, galleries and auction houses. Hugo Simon, a Jewish banker and finance minister based in Berlin and a supporter of many "degenerate" artists lost many works to the Nazis. He was also the owner of what recently became the world's most expensive painting, Edvard Munch's The Scream, which he consigned to a Swiss gallery in 1937. Rafael Cardoso, Simon's great-grandson believes that Simon only let the masterpiece go because of Nazi persecution.

The question is: did Simon consign the work in the normal course of business or did he have no choice? It was not clear he was paid for it. At the very least he probably saved this particular Scream (there are four versions) from destruction. Cardoso refused compensation offers from the consignor, Norwegian shipping magnate Petter Olsen, stating that his only issue was a moral one: "That the legacy of those who were wronged should be remembered and respected."

The sale went ahead regardless, and The Scream was sold for a record-breaking $119.9m to New York billionaire Leon Black, before loaning it to New York's Museum of Modern Art in May 2012.

Actions like this by museums, Cardoso believes, do harm to the memory of those who saved priceless works. One such person is Paul Rosenberg, who escaped to New York where he opened a gallery on 16 East Fifty-Seventh Street. In 1941 he sold a painting branded degenerate from the Nazis (who would have destroyed it) to MoMA. It was the first time it had been shown in a public museum. The painting is Van Gogh's Starry Night.

FAKES AND FABERGE

The contribution of Jewish art dealers to world art cannot be underestimated – neither can the harm caused by Nazi-wrought destruction. No one knows what other masterpieces might have been lost, and what is still out there, waiting to be discovered.

A touch of regal flair and a slight change of direction (from paintings to trinkets) is brought to the conference by 73-year-old Géza von Habsburg, aka Archduke Géza of Austria, Prince Imperial of Austria, Prince Royal of Hungary, Croatia, and Bohemia, who is the world's foremost expert on Fabergé – particularly the eggs.

Von Habsburg charms the audience with his knowledge and thick Austrian accent. "Ninety-nine percent of what is sent to me to authenticate are forgeries," he says before telling the jaw-dropping story of an "unnamed gentleman" from a Middle Eastern country who acquired a Fabergé collection for $60m in a private sale. "Every single item was forged . . . I suggested that to him that perhaps he could ask for his money back." The collector waved von Habsburg away, wanting to keep quiet about it.

No less entertaining is James -Martin, a tall, engaging scientist who uses hi-tech methods to expose fake paintings. Martin, the founder of Orion Analytical, describes the case of US forger, William Toye, who forged the work of Clementine Hunter, the daughter of slaves who started painting in her 60s. Her works sell for $5-$20,000, "perfect for staying under the radar," Martin says. The FBI was having trouble nailing Toye when Martin noticed, from photographs, that the artist owned lots of cats that had free run of his studio. The easy way to tell if you have a Toye as opposed to a Hunter, Martin says, is to check for cat hairs painted into the canvas.

Toye is nothing compared to 63-year-old Wolfgang Beltracchi, however, who forged hundreds of paintings over a period of 35 years, earning millions and fooling top collectors and -museums. Beltracchi, who with long hair and beard looks every part the artist, is the best forger Martin's been asked to scrutinise. Beltracchi's name, oft-mentioned at the conference, is spoken with loathing. Feigen ended up with a Beltracchi Max Ernst, eventually exposed by Martin (58 Beltracchi fakes have been identified so far). "I know the Max Ernst expert who issued authentication certificates on these fakes," Feigen says, "He's a wreck now."

Another Beltracchi Max Ernst La Forêt, (1927) was sold in 2004 for $2.4m after the same appraiser issued a certificate of authenticity. It was eventually sold to a collector for $7m. Beltracchi was sentenced to six years in 2011 (and he is able to go home during the day). The feeling at the conference (and this is putting it mildly) is that the authorities didn't take his crimes seriously enough.

The biggest victim is art itself. Beltracchi claims hundreds of his fakes are hanging in museums across the world. And no one is going to risk buying a Max Ernst after Beltracchi; a similar situation arose with Salvador Dalí after the -market was flooded with fakes.

Closing the conference, just before the delegates rush off to swap horror stories at the evening reception, Marinello says: "It's got to the point where it seems you have to have rocks in your head to buy art. You've got to perform due diligence, pay an appraiser, an art authentication expert, a provenance researcher, lawyers and even a scientist."

In other words, it's much easier to take up art crime. With little law enforcement, dealers prepared to look the other way and with no significant change in practice and regulation on the horizon, the business of fakes, forgeries, and looted and stolen art worth countless billions looks set to keep Marinello et al busy for decades yet.

Correction: An earlier version of this article not intended for publication stated that Cornelius Gurlitt was interviewed by the Monuments Men, it was in fact Hildebrand Gurlitt and the article was amended to reflect this. It also originally stated that Leon Black sold The Scream to the New York Museum of Modern Art. He in fact only loaned it and the article has been amended to reflect this. It also stated that MoMA didn't display the full history of the painting. As MoMA do not display the history of any paintings, this has been removed. The article also referred to Van Gogh's Starry Night currently hanging opposite The Scream. This was inaccurate and has been removed.