Teenagers who live in areas with poor air quality could be at greater risk of experiencing psychosis, researchers have found.

Past studies have shown that people who live in cities are more likely to have symptoms of psychosis, such as hearing voices and paranoia, as well as conditions like schizophrenia—of which psychosis is a symptom. This is an important line of inquiry, as 70 percent of the global population is expected to live in an urban environment by 2050.

In their study, published in the journal JAMA Psychiatry, the authors found that teenagers exposed to nitrogen dioxide (NO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and fine particulate matter (PM2.5) had a greater risk of experiencing psychosis. Regularly encountering a combination of NO2 and NOx explained 60 percent of the associations between urbanicity— what scientists call the effects of living in a city—and psychosis in teenagers, the researchers said.

The team studied data on 2,232 children who took part in the Environmental Risk Longitudinal Twin Study and were interviewed periodically from birth until they reached the age of 18. The participants were born between January 1, 1994, and December 4, 1995, in the U.K. nations of England and Wales. Of the total respondents, 2,063 gave information about psychotic experiences at the age of 18. They were asked questions, including whether they had thought they were being watched or spied on; or if they heard voices others couldn't.

Next, the researchers looked at levels of NO2, NOx and PM2.5 in the areas where the young people lived in 2012, as well as two locations they visited regularly.

The data revealed that 623, or 30 percent, of teenagers had at least one psychotic experience between the ages of 12 and 18. And those in the top quartile of exposure to the three substances were at a greater risk of psychosis.

This suggests pollution could directly affect the brain over a long period of time, the authors said.

Helen Fisher, senior author of the study at the King's College London Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience, told Newsweek the link between pollution and psychosis remained even when the team adjusted for other possible explanatory factors like smoking, using cannabis, alcohol dependence, poverty, other mental disorders, as well as living in poverty or an area of deprivation, high crime and poor social cohesion.

However, she acknowledged that since the study was observational with no randomized control group, it couldn't draw firm conclusions that air pollution caused psychosis. And as air pollution was measured around the same time as psychotic experiences, the team can't be certain that exposure to pollution happened before the psychotic experiences emerged. Other factors not assessed, like noise pollution, might also contribute to the risk, she said.

"Our study does add to the existing body of evidence linking air pollution to physical health problems such as cardiovascular and respiratory disease," Fisher said. "Our study also adds to emerging evidence linking air pollution to the brain and psychiatric conditions such as dementia. However, further research is required before any conclusions can be firmly drawn about the role of air pollution in the development of mental health problems."

Dr. Marc Weisskopf, a professor of environmental epidemiology and physiology at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who was not involved in the work, told Newsweek: "The possibility that air pollution may contribute to mental health outcomes like psychotic events is very important and needs to be understood.

"I would certainly expect that if this kind of thing is happening in the U.K., similar things would be found in the U.S.

"I think it is important to avoid excessive air pollution exposures, although at this stage I think there are more established outcomes that make that important."

Weisskopf also pointed out that the study was limited in some respects. "I remain unsure about how much of the association they [the authors] find with the air pollutants are truly effects of those pollutants, rather than those pollutants being just a marker for some other aspect of urbanicity."

Sophie Dix, director of research at the charity MQ: Transforming Mental Health, commented: "This study adds important new insight to the discussion on the links between mental health and urban living. The relationship between living in a city and increased mental illness has been something that has been explored for a long time, with many factors considered responsible. This study is significant because it provides a starting point with a possible link between pollution and psychosis, giving future research a platform to build upon. Ruling risk factors in, or out, is helpful in determining how we can best address the issue."

Like Weisskopf, she also said more work needs to be done to prove causation. "There is no evidence that pollution necessarily causes psychosis or whether this is one of many factors or acting in isolation. There is a bigger picture here, but that does not diminish the importance of these findings and the potential that comes from this."

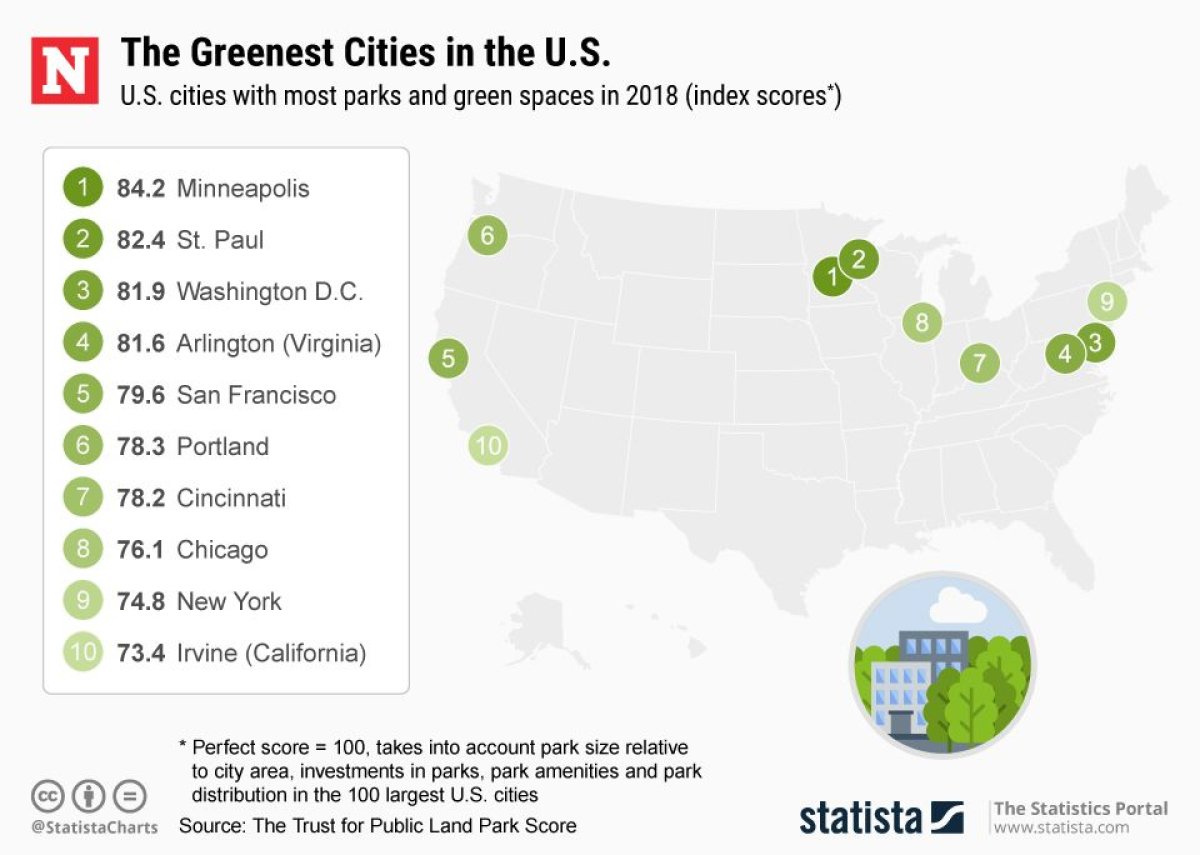

This graph, provided by Statista, shows the "greenest" cities in the U.S.

The study is the latest piece of research to suggest air pollution could be harmful to health. Earlier this month, a paper published in the European Heart Journal revealed air pollution, including fine particulate matter, is killing 8.8 million people worldwide each year. That's almost double the figure previously thought.

Professor Jos Lelieveld of the Max-Plank Institute for Chemistry in Mainz and the Cyprus Institute Nicosia, a co-author of the study, told Newsweek at the time: "We had not anticipated such a large increase.

"We hope to show that it is urgent and important to further reduce fine particulate matter in ambient air. The main message is that PM2.5 air pollution is a health risk factor that is comparable to other main risks such as hypertension, diabetes and tobacco smoking."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kashmira Gander is Deputy Science Editor at Newsweek. Her interests include health, gender, LGBTQIA+ issues, human rights, subcultures, music, and lifestyle. Her ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.