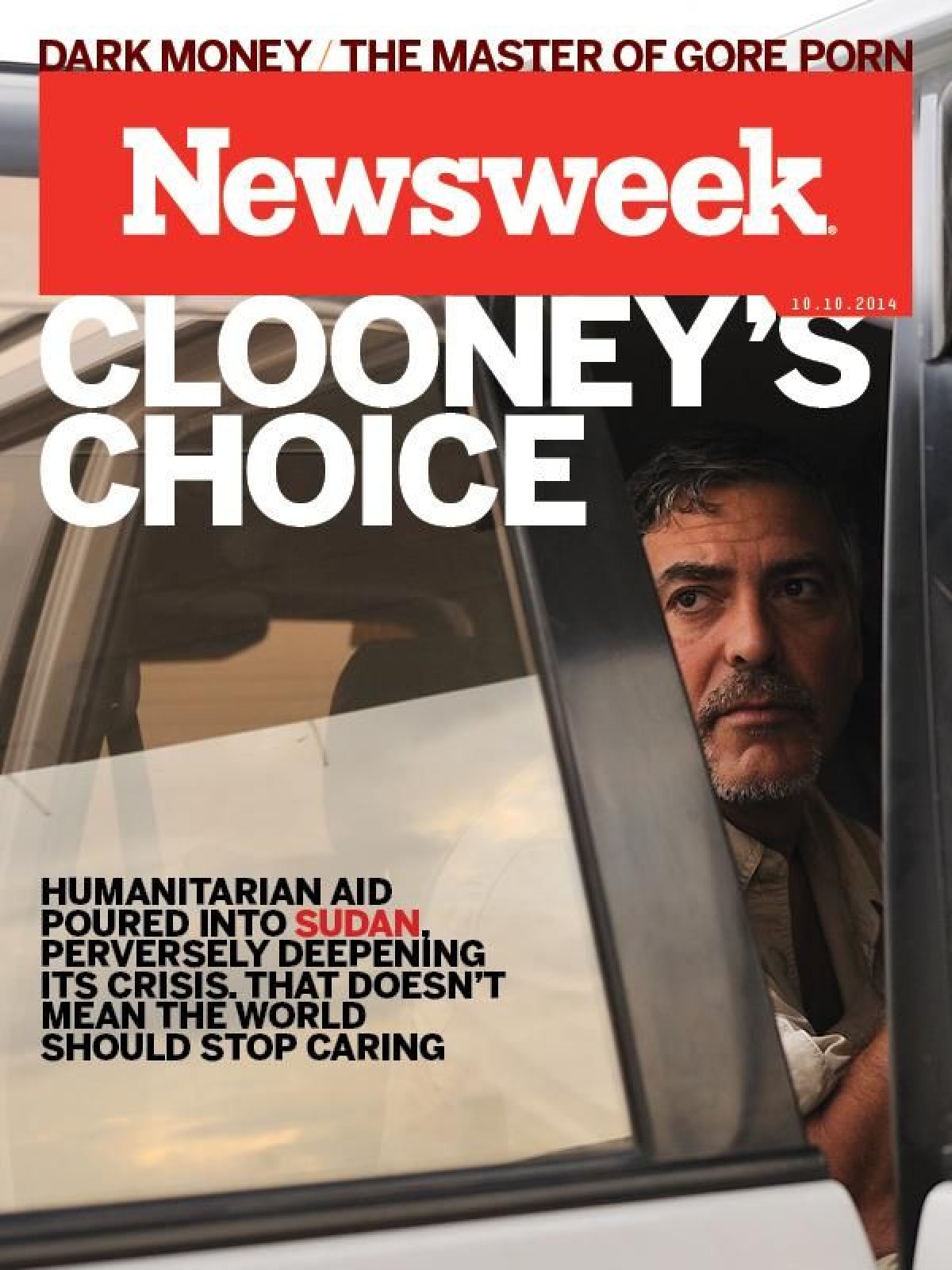

Writer Alex Perry spent eight years as bureau chief for Time magazine in China and India before moving to South Africa in 2006 to cover the African continent. He first started visiting South Sudan in 2009, the location of his latest story for Newsweek: "George Clooney, South Sudan and How the World's Newest Nation Imploded."

In a Q&A, Perry, now based in the U.K., discusses the challenges of reporting on the vast and diverse continent and the growth of the humanitarianism movement. Edited excerpts:

How did your perceptions of the continent change over the eight years you spent reporting from there?

The impression you get of Africa from the outside, and particularly from Asia, is a pretty one-dimensional one of never-ending tragedy, sorrow, disease, famine, the works, the starving baby. Of course, that's immediately disproved when you arrive. It's the most diverse continent in the world; ethnically, linguistically, geographically. Its desert, its snow-capped mountains, its tropical forest—it's so big. It's ridiculous to try and classify it as any one thing.

The idea that it was a monolith of suffering was also completely wrong. Africa was growing incredibly fast, [and] had been for a number of years by the time I arrived, [with] some of the fastest growing economies in the world. That transformation was really what I spent a lot of my eight years covering. That's not to say there aren't hefty obstacles in the way of Africa lifting itself out of poverty. The three big ones were bad leaders, jihadis, which are having a whale of a time in Africa right now, and aid groups, who essentially, as we talk about in the piece, for all their good intentions … displace people from running their own lives.

You can't talk about aid as charity anymore, it's a huge business. And like any business, it protects its interests and tries to grow and it does that by painting Africa to the rest of the world as a place of permanent crisis to which you should send more money so that we can fix it.

One of the reasons it's difficult to grasp the vastness of the continent is that its history is so complicated, for each country, each state, each border. What was the biggest challenge in trying to very concisely pull together the history behind the creation of South Sudan?

It's long and deep and very intricate and also not very well known. Sometimes you find that, there simply isn't reading to do. You've got to go there and ask people. A lot of the history is sort of in people's minds, it's an oral remembrance. That, in itself, comes with its own complications because that changes over time and according to the person who is telling it. In that sense, it's a constant learning process.

With this story, however, the subject was the humanitarians. This isn't a question of agreeing that the foreigners are the subject of Africa's story, but in this particular case we were focusing on the humanitarian effort. They are rightfully the subject of that story. As much as I was looking into South Sudan's past, I was looking at where humanitarians come from, what were the origins of this movement, how come it's gotten so big. That, to me, was a revelation.

Why was it important to explore the history of the humanitarian movement in Africa?

This movement was a small little kernel inside the 1960s protest movement, very idealistic, very anti-establishment in a sense, very anti-the Cold War establishment at the time. It was trying to almost do away with any politics of left or right and just say: "We're going to be neutral and we're going to help people."

To me, because the movement was so grounded in how a certain group of Westerners wanted to find themselves, that's incredibly telling. Its origins, its motivations are about how this group of people looked at themselves and how they wanted to be in the world. The question of who they were going to help was sort of secondary. This was about being a better type of person. If that's where the origins are, it's an introspective kind of thing, a self-regarding kind of thing. What's problematic about that is if you go out into other people's lives and other countries with that kind of motivation, you're going to be displacing people, you're not going to give much regard to their autonomy or freedom.

The Daily Beast's John Avlon said the piece was cynical and that you turned "moral obligation into moral relativism." How do you respond to that?

John Avlon wrote the piece on Clooney three years ago in Newsweek, which was the polar opposite. It was the most "pro-white Savior" piece I've ever seen. The truth is, Clooney is a smart guy, he completely understands all the problems we raise in the piece. That, in fact, was the essence of a lot of the conversations that I had with him. Nothing in that piece is not well-known to the humanitarians. It may all be news to John Avlon, but we're not breaking any news here to the humanitarian world. They're well aware of these contradictions and dilemmas and conundrums and they spend a lot of time debating them amongst themselves and trying to come to some sort of resolution.

The point is, when you have a situation like south Sudan which implodes in a catastrophe, and humanitarianism had a major role in creating south Sudan, I think it's irresponsible not to examine what humanitarians might have done better.

Earlier this year, a survey by the Pew Research Center found that many Americans want the U.S. to step back from intervening abroad and focus on problems at home. Since then, the U.S. has been drawn into two major global crises: the rise of the Islamic State and the outbreak of the Ebola virus in West Africa.

Obama's foreign policy is kind of another illustration of the dilemmas and conundrums [faced by the U.S.]. You don't want to be the interfering bully, bossing the world around telling it what to do. It doesn't work, it backfires. It backfired massively on George Bush. I think there's a general recognition in the U.S. and in other foreign interventionist policy that there should be limits as to what you do and how you interfere in what is after all, sovereign territory around the world. Imagine if the Cambodian government decided that what the U.S. was doing in Los Angeles was appalling and it was going to intervene out of humanitarian concern? It's unthinkable. But that's kind of how this sort of thing is seen in places like Cambodia. You're violating sovereignty and freedom and self-determination. And you've got to be pretty sure of your grounds if you're going to do that.

On the other hand, when you have someone like Assad or a regime like North Korea, or Libya, or mention any number of atrocities in the world this year like the Central African Republic, do you just stand by and let it happen? It's a real dilemma and I don't really think that anyone can ever come up with a good answer. Each case needs to be considered on its own merit.

If you're going to take this role on of perhaps going into some situations and not going into others, you've got to be prepared for criticism of everything you do because for some people it will never be enough and for [others] it will always be too much. You're never going to get thanked, you're probably going to get drawn into deeper into conflicts than you want to be. When you stay away, you're going to be accused of being callous and selfish. These are sources of dilemma that I was trying to explore in the piece.

Alex Perry's in-depth ebook Clooney's War: South Sudan, Humanitarian Failure and Celebrity is available now from Newsweek Insights.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jackie Bischof is a Queens resident, by way of Johannesburg, who has written and produced for a wire, magazine, websites ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.