Two years ago, Rob Hegel had his "magic bean moment." Hegel, the director of purchasing for a Hilton Hotel in Los Angeles, was walking through a trade show in New York when someone handed him a test tube filled with white nylon beads half the size of a Tic Tac. "The person told me that what I was holding would not only save me hundreds of thousands of dollars—it would save the environment too," Hegel says.

Earlier that year, with California's rivers and reservoirs at record low levels, Governor Jerry Brown declared a drought state of emergency. "We can't make it rain," he said while establishing strict water-conservation measures. He called upon all Californians to save water in "every way possible."

Hegel had gone to that trade show in search of new ways for his hotel to comply with Brown's measures, so he was intrigued by the vendor's claim. Those "magic beans," he learned, were the key component of an ultra-low water laundry system developed by the U.K. cleaning startup Xeros.

The salesman said Xeros washers would deliver superior cleaning results compared with conventional washers, while using 50 percent less energy, 50 percent less detergent and 80 percent less water. Hegel was skeptical, but with thousands of pounds of dirty linen to wash each week, he decided to give one machine a try.

Hegel and his people were stunned to find that the trade show salesman was being modest. "After installing the first machine, we found that it actually used 90 percent less water and very little chemicals—and the laundry results were incredible," he says. "Our director of housekeeping was ecstatic."

The bead technology used in Xeros machines emerged from the University of Leeds School of Textiles in the U.K. 10 years ago, when researchers found that tiny nylon beads mixed with a small amount of water and special detergent could act as a sponge to "soak up" dirt from fabrics.

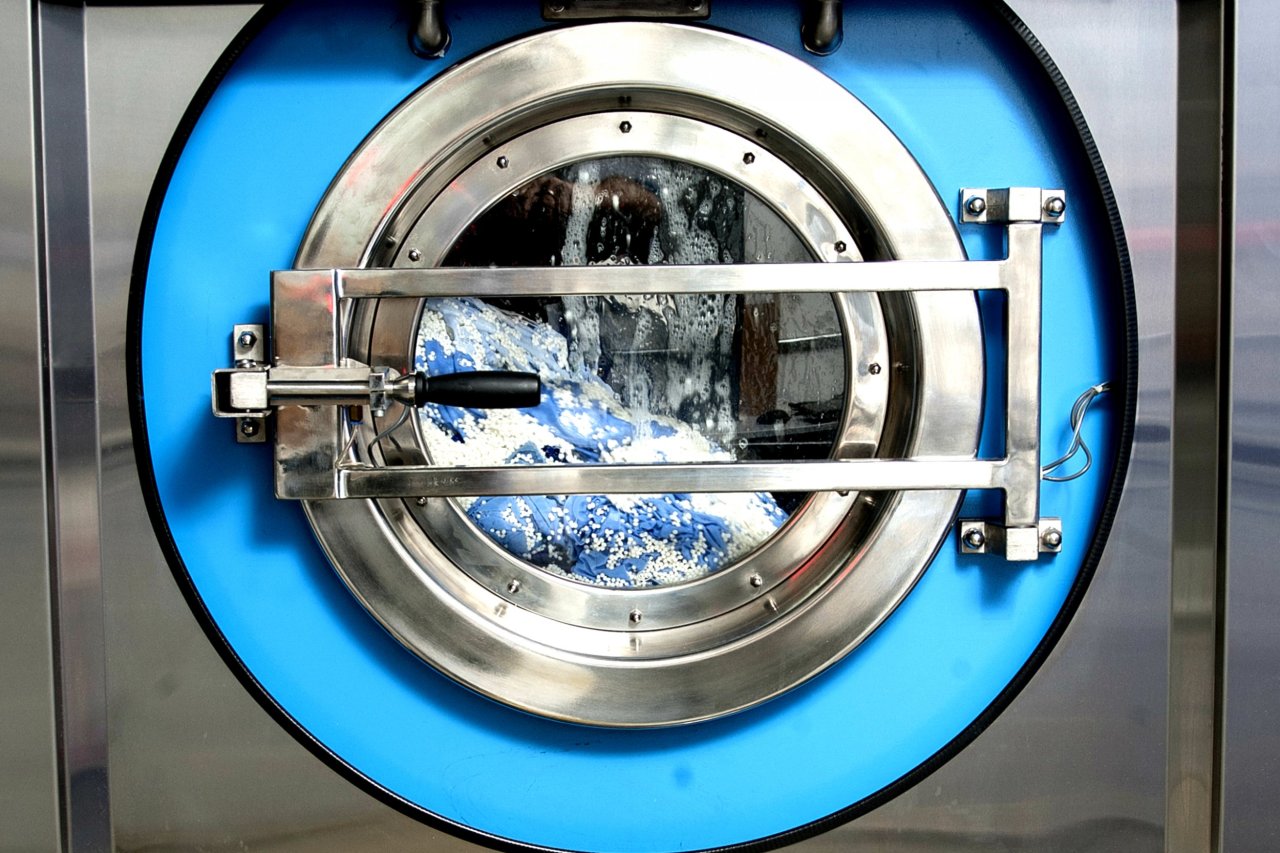

The machines that resulted from this research look similar to modern washers, but could represent the biggest leap forward in the laundry industry since electric-powered washing machines rendered wringers obsolete in the early 20th century.

The near-waterless washers use hundreds of thousands of beads. The company claims this method is as gentle on fabrics as hand-washing and therefore does a better job of caring for the material than traditional machines do. The system has the added benefit of preventing a rogue red sock from turning a white laundry load pink—the beads absorb not only dirt but also stray colors. Each batch of beads can be reused hundreds of times.

While the benefits in water-scarce California are clear—Xeros systems have been installed in 14 locations across the state, including several laundromats and one athletic club—getting hotels and businesses elsewhere to understand how plastic beads can be a more efficient method of cleaning than water has been the biggest challenge for widespread adoption. "People are used to using water, way back from when we used to wash our clothes in rivers," says Jonathan Benjamin, Xeros's global president of laundry. He says the company is also exploring other ways to apply the technology, such as within the water-intensive leather-processing industry. A full-scale trial that used Xeros's beads to dye hides in a tannery was successfully completed earlier this year. "Cleaning, dyeing—the potential for these beads is incredible," says Benjamin. "I'm not sure we're close to a point that we'll see humans bathing in polymer beads, but who knows?"

The California drought is into its sixth year and Hegel's hotel now has three Xeros machines, each one saving his hotel around $2,200 per month on water and energy costs. By the first quarter of 2017, the machines are expected to have saved 4 million gallons of water—the equivalent of six Olympic-sized swimming pools.

When Xeros sells a washer, it also sells a service that costs $1,500 per machine each month—for upkeep and maintenance, and for the collection and replacement of the beads. This makes the washers too costly and impractical for domestic use, but the company is working on a domestic version. If it succeeds in building and commercializing a home machine, the company could have an even greater impact in combating the California drought, since washers account for 21.7 percent of all residential water use. (Figures on commercial laundries are not available.)

Even so, the drought in California could outrun technology. If every washer in California was replaced with a Xeros machine, many problems would remain—most notably with agriculture, which accounts for 80 percent of all water used in the state.

Climate change is a further problem. In 2015, climate scientists at Columbia University found that human-caused global warming had caused the California drought to intensify by 15 to 20 percent, and statistical projections warn of another drought year for 2017.

Benjamin thinks we need to take a long-term view to end critical water shortages. "We've reached a point where the world needs to redefine how we use water," he says. "Water should be used just for consumption."