More than 86 percent of adults aged 20 to 39 are affected by tooth decay. This means most people have had at least one or two cavities filled in their lifetime, and probably more. A silicone-based cement is used by dentists worldwide to fill holes that remain in teeth when a dentist clears out the infected, decayed part with a drill. These dental fillings for cavities do the job, but wear and tear, as well as hard or chewy foods, can loosen them, increasing the risk of infection and decay.

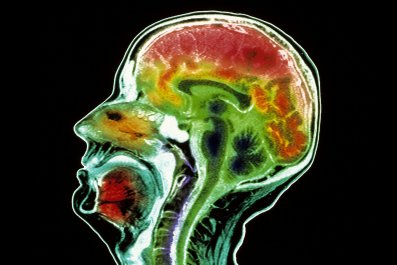

Teeth are composed of two different types of minerals. The outer covering is a thin layer known as enamel, which protects the tooth. It's dead. Underneath the enamel is a thicker layer, similar to bone, called dentine. This forms the inner core of the tooth and protects the soft tissue or pulp underneath. Dentine is alive with nerves and gives the tooth its sensation. It has the potential for regrowth but needs some help.

An emerging field in dentistry known as regenerative endodontics is on the hunt for a natural solution that could do away with fillings. Researchers in the U.K. might have found one—they have used a drug to stimulate the regrowth of teeth in mice. The work was done by Paul Sharpe, a professor of craniofacial biology at King's College London, and his colleagues.

Sharpe and his colleagues drilled tiny holes in the mice's teeth. Next, they applied a drug called Tideglusib to the teeth, with the aid of a tiny biodegradable sponge made of collagen that they left in the hole. Tideglusib has bee n studied extensively and has already passed safety testing as a treatment for symptoms of Alzheimer's disease. The drug activates the Wnt signaling pathway, which appears to be involved in stimulating cellular-based repair of all tissue. They found that by as early as the fourth week, the dentine had filled out and the sponge had effectively disappeared.

"It greatly enhanced what the tooth tries to do naturally, but it does it in a much more robust way and much quicker," says Sharpe, who published the findings in the January issue of Scientific Reports.

Rena D'Souza, associate vice provost for research and professor of dentistry at the University of Utah, has been involved in similar research. She says this experimental treatment won't be ready for humans for some time. "The next step would be to create an infected tooth to see if the therapy works when you have inflammation present, and then you could go to larger animal models," she says. For some mice, that might mean a lot of treats—and some very painful consequences.