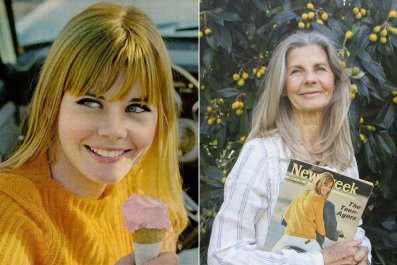

In 1966, Newsweek published a landmark cover story, "The Teen-Agers: A Newsweek Survey of What They're Really Like," investigating everything from politics and pop culture to teens' views on their parents, their future and the world. The article was based on an extensive survey of nearly 800 teens across the country, and it also profiled six teens in depth, including a black teen growing up in Chicago, a Malibu girl, and a farm boy in Iowa. Fifty years later, Newsweek set out to discover what's changed and what's stayed the same for American teens. The result, "The State of the American Teenager," offers fascinating and sometimes disturbing insights into a generation that's plugged in, politically aware, and optimistic about their futures, yet anxious about their country.

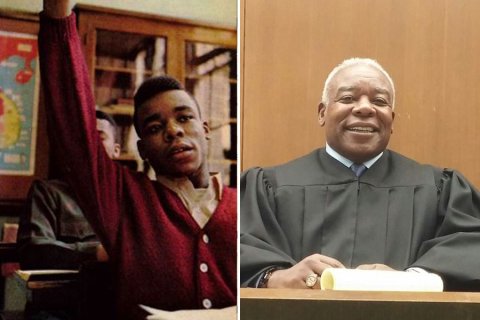

Growing up in the projects of Chicago's South Side in the 1960s, Tommy Brewer used to watch ABC's The FBI on Sunday nights with his father. "I said one day, out of excitement, 'I wanna be an FBI agent!'" recalls Brewer. "And my father said, 'You're not allowed in the FBI. They don't allow blacks to be FBI agents.'" Brewer's father was a steelworker with a sixth-grade education, and his mother didn't make it past the fifth grade. But Brewer, surrounded by gangs and violence, was convinced an education would get him wherever he wanted to go in life. So each morning, he took two buses and an L train to Lindblom Technical High School, where he got A's (and one B) and took honors courses. He dreamed of going to college and studying architectural engineering.

"If teenagers have the right education, they won't have any problems," he told Newsweek in 1966, when he was 15. "The gang members were taught this, but it just didn't sink in.… When they get to be 18 and it's time to get a job, then they find out that they need a good high school education to land one. So crime is the easiest way out. There's no pressure like there is in school."

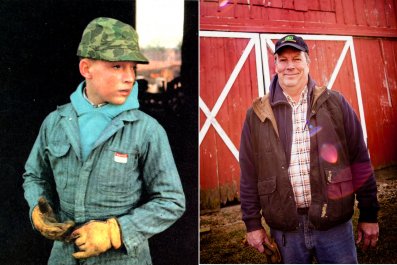

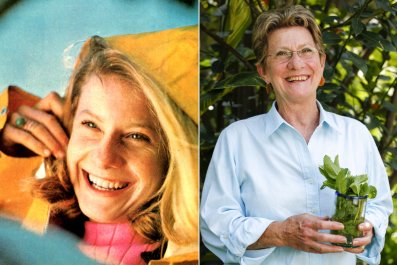

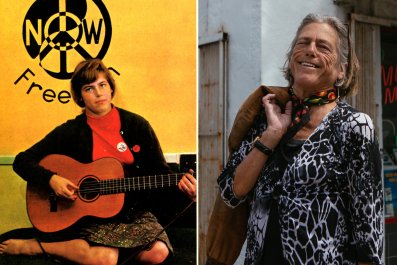

Brewer's story was part of a landmark 1966 cover story, "The Teen-Agers: A Newsweek Survey of What They're Really Like." The 18-page spread investigated the teen world in fine detail: their heroes, politics, spending habits, sexual proclivities and exercise habits, as well as what they thought about the world, their parents and their future. The article was old-school journalism at its best: Correspondents in Newsweek bureaus fanned out to cities and small towns across the country, interviewing hundreds of teens as well as parents, psychologists, principals and other experts, while the famous pollster Louis Harris and Associates conducted an extensive survey of 775 girls and boys. Newsweek also profiled six teens in depth: a farm boy from Iowa, a California girl, a Manhattan prepster, a free spirit from Berkeley, a middle-school girl in Houston and Brewer.

This past fall, in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of "The Teen-Agers," Newsweek enlisted Harris Poll to conduct an online survey replicating key questions in the original work and to expand on it. We asked 2,057 teens, ages 13 to 17, from diverse backgrounds and geographic areas, about everything from politics and education to parents, sex, mental health and pop culture. The result, "The State of the American Teenager," offers fascinating and sometimes disturbing insights into a generation of teens who are plugged in, politically aware, and optimistic about their futures yet anxious about their country.

[RELATED: The State of the American Teenager: 1966 vs. Now]

Two-thirds of teens (68 percent), for example, believe the United States is on the wrong track, and 59 percent think pop culture keeps the country from talking about the news that really matters. Faith in God or some other divine being dropped from 96 percent in 1966 to 83 percent. Twice as many teens today feel their parents have tried to run their lives too much (24 percent, up from 12 percent in 1966). Fifty years ago, the five most admired famous people were John F. Kennedy, Abraham Lincoln, George Washington, Lyndon B. Johnson and Helen Keller, in that order. Today, pop culture rules, as President Barack Obama, Taylor Swift and Beyoncé top the list, with Selena Gomez tying Lincoln for fourth place.

More than half of teens support gun control (55 percent), the death penalty (52 percent), abortion rights (50 percent) and gay marriage (62 percent). (On her support of gay marriage, Allison Moseley, 16, of Cudahy, Wisconsin, says, "Love is love.")

The most compelling findings show that race and discrimination are crucial issues for teens today. In 1966, 44 percent of American teens thought racial discrimination would be a problem for their generation. Now nearly twice as many—82 percent—feel the same way. The outlook is more alarming among black teens: Ninety-one percent think discrimination is here to stay, up from 33 percent in 1966.

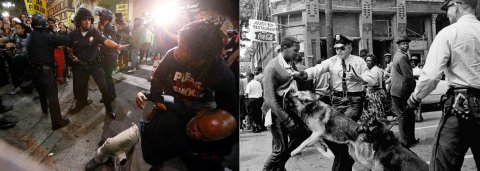

Recent headlines—police-involved shootings of unarmed black men, the Black Lives Matter movement, Donald Trump's xenophobic politics—reveal a country deeply divided on race, with seemingly little hope for reconciliation. For many black Americans, the entire casino is stacked against them: They're disproportionately affected by unemployment, poverty and a lack of educational opportunities. The U.S. has the highest incarceration rate in the world, and while blacks and Latinos make up 30 percent of the population, they account for 58 percent of the prison population. In 2013, the wealth gap between whites and blacks reached its highest point since 1989, according to the Pew Research Center: The wealth of white households was 13 times that of black households, and 10 times that of Hispanic households.

Newsweek found that black teens today are more likely than white or Hispanic teens to be aware of gun violence and of police officers accused of killing innocent people. They're also more likely to worry that they'll be the victims of shootings—at school, by police or in places of worship. And m any teens, regardless of race or ethnicity, perceive that black Americans are discriminated against at higher rates than others, including the way they're treated by police (62 percent) and their ability to access decent jobs (39 percent).

And what's happened to Brewer's seemingly indomitable optimism over the past 50 years, his unwavering faith in education? "I wouldn't want to be growin' up now," he says. "It was simpler back then. The choices you had were limited, but they were good and positive. You had to work for what you wanted, and if you were black, you had to work doubly hard….

"To wake up every day knowing for the rest of your life you're gonna be broke, what's a person to do? You're not vested in America. We were vested."

The supportive environment Brewer came of age in was marked by family, community and the belief that hard work would pay off. For many Americans today, those pillars have been toppled. "Back in the '60s, we had black poverty, but we also had black jobs," says Kirkland Vaughans, a psychologist who teaches at Adelphi University and co-authored The Psychology of Black Boys and Adolescents with Warren Spielberg. "You can be poor, but as long as you have someplace to go, you have hope. Joblessness has grown, and the criminal-industrial complex has grown."

At the same time, the U.S. population is on track to be a minority majority by 2060: Minorities will make up 56 percent of the country, up from 38 percent in 2014, and in just four years, more than half of all children in the U.S. will be part of a minority group. What does the future look like for a country that's still wracked by racism, where four of five teens believe discrimination will be a fixture in their lives?

1966: The Illusion of Carefree

In March 1966, Newsweek's "The Teen-Agers" issue hit newsstands with a young blonde on its cover—a California girl in white Wranglers and a yellow sweater, sitting on the back of a motorcycle, clutching a guy and flashing a spectacular smile. The scene encapsulated the stereotypical 1960s teenage experience: fast-paced, forward-thinking, titillating, seemingly carefree.

Newsweek's original survey found that teens were generally happy, liked school and felt extraordinary pressure to attend college ("Which is more important, the morality of cheating or getting into college?" a 17-year-old girl asked). They owned records, transistor radios and encyclopedias (today, smartphones, laptops and tablets dominate). It isn't until the fifth page—after sections labeled "The Group," "They're Spoiled," "Living in School," "The Place of Sex" and "Freedom on Wheels"—that the article admits, "There are also the Negroes," before delving into a section called "Hopeful Outsiders." We learned about the aspirations of black teens in 1966: Forty-one percent were "certain" they'd go to college; their mood: 22 percent said they were less happy than at 8 or 9, compared with 8 percent of the survey sample; their family dynamics: 38 percent said parents exerted "a lot of pressure" on them, compared with 18 percent of the entire group. And we heard about their fears: Thirty-one percent thought life would be worse when they reached 21, compared with 25 percent of all teens.

We also met a 16-year-old black teen from Los Angeles's Watts ("Yeah, I was in [the riot]. I didn't do none of the burnin', but I was lootin'.") who attended an almost entirely black high school, wasn't sure he could get into college and felt "scared" of the future. Yet his optimism prevailed: "He still believes white employers will treat him fairly if he is 'qualified.' He is not bitter. 'I'm not gonna drop out. If I can't get into college, I'll probably go out and get a job."

One of the most positive notes on race came from Brewer, who even had some sly thoughts on desegregation. "Most of the reason for prejudice is because we know very little about each other," he told Newsweek in 1966. "Our neighborhoods are different, and so we have little contact. Every time some of us move into an area, they move out. Eventually we have to communicate because they are running out of places to move to."

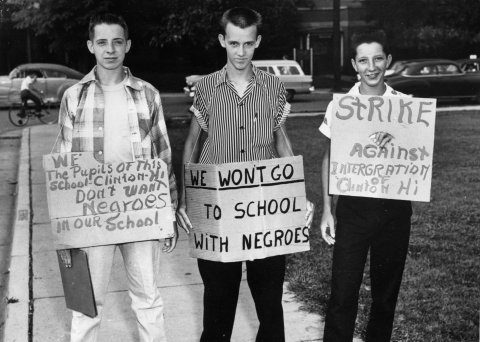

"The Teen-Agers" presented a generation optimistic about the future (even as its members sometimes feared it). And that's not so surprising, since the civil rights movement was celebrating some major triumphs at the time. Segregation in public schools had been declared unconstitutional in 1954 with the Supreme Court's decision in Brown v. Board of Education. By the early 1960s, black Americans were staging sit-ins and freedom rides in the South, challenging whites-only lunch counters and segregated transportation. In 1963, more than 200,000 Americans attended the March on Washington, which concluded with the Reverend Martin Luther King's transcendent "I Have a Dream" speech. (He did not, however, make the list of 13 famous people teens admired most in '66.) The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was signed into law by President Johnson, banning discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex or national origin.

School integration lurched forward. The Black Panther movement rose. Yet segregation persisted. In 1965, Alabama state troopers and local police assaulted 525 civil rights demonstrators as they marched peacefully from Selma to Montgomery. Officers charged into the crowd, some on horseback wielding nightsticks and firing tear gas, leaving more than 50 people injured on what became known as Bloody Sunday. Soon after, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which prohibited discriminatory voting laws. That same year, the Immigration and Nationality Act meant immigrants of all nationalities could come to the U.S. on an (almost) equal basis.

"There was a sense of hopefulness—not just with African-Americans but with all people—that the country was generally on the right track," says Arun Venugopal, host of Micropolis, WNYC's semi-regular show on race and identity. "Economically, the country was doing really well. A lot of jobs were being created. If you were young, there was a sense that you had a good chance of being gainfully employed. Minimum wage took you a lot further then than it does today."

As a teen, Brewer had a concrete vision of his future: a career, not just a job; marriage, but not before his mid-20s; a family, but not until he could support one financially. It has all come to pass. He earned a scholarship to Williams College, got his law degree at Northwestern and, a couple of years later, joined the FBI. "At the time, there were 118 black agents out of almost 9,000. Me and another guy were one of the few from the North, both from public housing, and that was unheard of in the bureau," he says. He got married at 30 (then married two more times; he has two daughters, ages 32 and 26, and a 3-year-old son). Today, he's a judge of the Cook County Circuit Court in Chicago, where he estimates that of the 480 people he has sentenced, only 5 percent graduated from high school, and 99 percent of the men were unemployed or underemployed.

Brewer credits his success to his parents, his community and something impossible to replicate: the '60s. "There was a big buzz about the possibilities for blacks at the time. We saw black stars on TV. We knew changes were coming: Opportunities that weren't available before would be. The FBI would be available. We didn't know how or when, but it was like, Be prepared! Education was a key," he says. "It was almost like a big candy factory was gonna open up for us. Today, the factory is open, but there's not much candy."

2016: Civil Rights and Wrongs

Many children growing up in America have access to life-changing opportunities—like earning a college scholarship or watching an older brother marry his boyfriend—and minor privileges, like getting the answer to literally any question in recorded human history from the Google search box on a smartphone and streaming Game of Thrones on lightning fast LTE during a math quiz. They can also watch video footage of 12-year-old Tamir Rice playing with a pellet gun outside a recreation center—then getting shot dead a moment later by a police officer. They can hear Eric Garner, 43, gasp "I can't breathe" as police officers place him in an apparent chokehold during an arrest for allegedly selling loose cigarettes, and they know that he'll be dead in less than an hour. And they can witness massive protests erupt in Ferguson, Missouri, after the death of 18-year-old Michael Brown, an unarmed black teenager shot at least six times, including twice in the head, by former police officer Darren Wilson, who's white.

A Guardian study found that, last year, young black men were nine times more likely than other Americans to be killed by police. The Washington Post reported refinements on the same depressing point: Unarmed black men were seven times more likely than whites to die from police shootings last year. According to a ProPublica analysis, between 2010 and 2012, black teens were 21 times more likely to be shot dead than white teens.

Discrimination has always been an American battleground, but teens today are growing up in a world where it seeps into the crevices of everyday life in new and sinister ways. While the country's first black president is finishing his second term, Trump has become the Republican front-runner in the upcoming presidential election, energizing a base the Atlantic describes as middle-aged white men without college degrees who don't think they have a voice, fear outsiders and hail from areas rife with racism. Last December, during an affirmative action case, Justice Antonin Scalia asked from the bench whether black students might do better at "a slower-track school" than at the more competitive colleges and universities. In September, Governor Paul R. LePage (R-Maine) blamed local drug use on "guys with the name D-Money, Smoothie, Shifty" who bring heroin to Maine and "impregnate a young white girl before they leave." LePage's head of communications, Peter Steele, defended his boss by explaining, "The governor is not making comments about race. Race is irrelevant."

Racism has roiled pop culture too. When not a single person of color was nominated for best actor, best actress, best supporting actor or best supporting actress at the 2016 Academy Awards, and no films featuring black actors got best picture nods, prominent black celebrities, including Spike Lee and Jada Pinkett Smith, boycotted the show. The controversy spawned the hashtag #OscarsSoWhite, and while the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences vowed to double the number of minorities and women by 2020, host Chris Rock said in his opening, " You're damn right Hollywood's racist." At this year's Super Bowl halftime show, Beyoncé turned her performance of a new song into a political statement on police brutality, racism and Hurricane Katrina. The conservative right was outraged: She and her backup dancers were dressed like the Black Panthers! " You're talking to middle America when you have the Super Bowl," former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani said. "Let's have, you know, decent, wholesome entertainment and not use it as a platform to attack the people who, you know, put their lives at risk to save us."

"Teenagers are growing up under this black president, yet at the end of his presidency we are seeing a constant stream of police killings and a new civil rights movement that's really turning the narrative on its head," says Nikole Hannah-Jones, an award-winning reporter who covers civil rights and racial injustice for The New York Times. "But I don't know our kids are getting the tools to deal with that. Research shows millennials are no better at race than our generation because these kids still are not being educated together. Even when they are in the same school buildings, they are not educated together. White and Asian kids are tracked into higher-level classes, and black and Latino kids are tracked lower.… Someone has to give up something so someone else can get equality."

But that's not happening, and black Americans still face inordinate disadvantages. "A black male with a college degree looking for a job will not do as well as a white male with a high school diploma looking for a job," says Vaughans. "A black male without a criminal record will not do as well as a white male with a criminal record if they get to an interview. If you are a black male with a name like Jujuan, or if you are a black male and went to Howard, hang it up."

Brewer's success was exceptional—a product of not just his staunch optimism and determination but also his community. Despite the tangle of violence and adversity in public housing in the 1960s, "there were mothers and fathers—whole families," he says. He grew up eating dinner every night with his parents and five siblings. No TV. No fast food. Just home-cooked meals, family and conversation. "I didn't know anyone who was chronically unemployed. And most fathers, if the son became 17 or 18, they could take them to their job and put 'em on. 'You're hired.' They raised families on the money they made. But all those jobs changed," he adds. "Now you have families disintegrated…. We all looked at public housing as being upward-bound, not as a decline. It's a different world today."

Osariemen, 15, from Brooklyn, New York: "The most challenging thing in my life is hearing bigots in my school voice their opinion like no one will be offended, like they shouldn't be held accountable."

Andrew, 17, from Ridgewood, New Jersey: "Blacks and whites are too confrontational about everything. I regard myself as being liberal and progressive, but there's no need for confrontation. Black people now, so many of them, they've got this idea that everybody is attacking them. We've gotta love each other. It's not 'them' against 'us.' It's all 'us.' Black Lives Matter. Well, all lives matter."

Jorge, 13, from Las Vegas: "Race is a problem in my life. In my school, I hear a lot of racist words. The black teenagers say the N-word. They call Mexicans and Asians in a negative way. It feels bad."

Shylee, 16, Tampa, Florida: "Black people try to separate themselves. They even have their own TV network. If you're trying to all be equal, why are you separating yourself from everyone? I'm not racist. I have nothing against them. I think there's definitely bad white people who don't like black people, but there's also bad black people who don't like white people."

Sophie, 16, Greensboro, North Carolina: "My dad makes an extraordinary amount of money, and we live in a very nice part of town.… We have a lot of very expensive things. I try to think about my privilege as much as I can, because I know a lot of people really don't have the race and class privilege that I do. It's definitely not something I deserve or another person doesn't deserve."

Rissa, 16, Indianapolis: "Everybody has to realize that skin color is nothing more than someone having more pigment than someone else. Until people realize that, we'll still have those people who are extremely racist.… We're programmed to find flaws in others and extort them."

The Great Transformation

Teens know racism is the issue of their generation, and many of them are working hard to understand it, confront it, change it. For some, this is a quiet, personal battle.

"One time, I was sitting in my room wearing a T-shirt, and my grandma came in and she thought the reason my skin is the way it is is because I don't take enough showers. Or I'm dirty. She thought if I cleanse myself harder, I'll have lighter skin," says Leuna Rahman, 17, of Queens, who identifies as South Asian (her parents are from Bangladesh). "That's not how it is. I was born this way."

Asked what she tells her grandmother, Rahman says, "I ignore it. You hear it so often, you just give up on fighting back. But I don't let it get to me, because I learned to love myself."

She's sitting in the basement of a brick church in Elmhurst, Queens, which moonlights as the headquarters for South Asian Youth Action, a youth development organization for 2,000 elementary, middle and high school students in New York City, focusing on academics, college prep and leadership skills.

"I did not want to be black," says her friend, Loretta Eboigbe, 18. "There's this notion that if you're light-skin, it's the right skin, or you're prettier.… At one point I went to the bathroom and tried to get rid of my skin color because I wanted to be white. I was around 7 or 8. I took a sponge and tried to scrub off my skin."

Eboigbe was born in Verona, Italy, and moved to the U.S. in 2008 because her parents, both Nigerian, wanted to live in a less homogenous environment. "I thought I'd be surrounded by diversity and people wouldn't judge me based on how I looked. But people made fun of my hair and accent. If people are constantly throwing racist comments at you, especially at a young age, there's no way to stand tall and be proud of who you are," she says.

Rahman nods. "During the Paris attack, a friend sat down and said, 'Can you tell your family not to kill my family? I heard Bengali people are also part of ISIS.'" She looks up with big, quizzical eyes. "Why would you just assume my family is a part of ISIS?"

"I was always hoping that once I got to college it would stop, and I'd find people like me. But now I'm transitioning into a world that might be the same," says Eboigbe, who's going to Brown this fall. "To see racism happening on college campuses, people being victimized, it's scary."

It's a grim outlook: Nearly twice as many teens—and nearly three times as many black teens—think racial discrimination is here to stay, compared with 50 years ago. The internet has given them a front-row seat to some of the greatest civil rights moments of their young lives. They've witnessed injustice (Ferguson), outright racism against their president (61 percent of Trump supporters don't believe Obama was born in the U.S.) and too little change coming too late (the Oscars). "Young people who otherwise couldn't participate in robust conversations like this all of a sudden now can participate as fully as anyone else. That is a powerful thing. We can't fix what we don't address," says DeRay Mckesson, the Black Lives Matter activist running for mayor of Baltimore.

"It's not only that teens can go to 1,000 websites but they can take to Twitter and Instagram and record their reactions about what's happening to them as they experience it," says Cornell William Brooks, president of the NAACP. "That represents a tectonic shift in the way young people process the social justice challenges of their time. This is not a graceful shift; it's a massive shift."

Racism may not look as it did 50 years ago—"It's not formally entrenched," Venugopal says—but it's endemic in our politics, economy, education system, popular culture, sports, health care and more. Changing one person's mind is difficult enough, much less overhauling society. Hannah-Jones lets out a long, forceful sigh when asked what advice she'd give teens. "Oh man! That's hard. Be better than your parents. Every generation, we think that as the old generation dies out, things will be better. But the new generation becomes the old generation, so I think if teens really want to see a day where there is real equality, they're gonna have to do a lot better job than we've done, our parents have done and our grandparents did. It's not inevitable but pretty damn close to inevitable that this generation will repeat our mistakes."

But what's the point of being a teenager if you can't make mistakes, and you can't change?

Moseley, the 16-year-old from Wisconsin—who's into the internet, model U.N. and, like many teens interviewed for this story, Bernie Sanders—is candid about her transformation on racism. "You have to be in a certain environment to change and learn that things are wrong," she says. Moseley wants to go to Yale or Harvard, and says the popular blogging platform Tumblr changed her. " Before I went on Tumblr, I was very racist and discriminatory, and after I went on Tumblr, I saw how people were struggling and how the things I was doing were wrong," she says. "Before, I wouldn't want to be around anyone of color. I'd be like, Oh my gosh, they're gonna mug me.…

"Now I'm just like, He's a person. I've learned that you cannot judge a person. You cannot stereotype. It's incredibly wrong to do."

In 1966, the 15-year-old Tommy Brewer wasn't particularly concerned with civil rights. "Most young people don't feel racial prejudice," he told Newsweek then. "We don't see the importance of civil rights yet. We believe in what Martin Luther King does, but we don't idolize him the way we do a baseball player."

Teens today may look up to Selena Gomez (as well as LeBron James, Jennifer Lawrence and Nicki Minaj), but they also idolize Beyoncé in part because she injected race, police brutality and civil rights into one of the largest, most American moments of the year. Brooks points out that in the past two years the NAACP has witnessed more racial conflict and challenges "than we've seen in nearly a generation," and has had 28 percent more young people join the organization online. "At a moment of conflict, crisis and challenge, rather than sliding into a civic and depressive funk, what do teens do? They join organizations. They take to Twitter. They do something about it," he says. Today, 75 percent of teens own smartphones. "And that's not because they can watch cat videos all day. But because they can engage in the world. And that says a lot about their character and morality."

Asked about the acute awareness teens today have about racism, Brewer sees cause for hope. "Race was and always will be a constant that black teens have to address, and to overcome that, you need to be qualified and equipped," he says. "The primary thing you need is education. We've got a black president now. Back then, we didn't have black mayors! But we had hope and belief, and we knew that all we needed was opportunity. Now you have more opportunity, but the preparation for it is just gone. It's hard to confront racism if you don't have education…. Children need training.

"There's so much freedom today. What do you do with it? Those things I learned as a kid [from my parents] served me better than what I learned in law school or in being a judge: Just being a decent human being, not being selfish and thinking outside yourself."

Obama, who knows a thing or two about breaking boundaries, rising above racism and raising teenagers, said in his commencement address at Howard University earlier this month, "If you had to choose a time to be, in the words of Lorraine Hansberry, 'young, gifted, and black' in America, you would choose right now."