A color pigment developed by the ancient Egyptians thousands of years ago may have an extremely beneficial application today, research has found.

In a paper published by The Journal of Applied Physics, a team led by researchers at the Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory found that the pigment, known as Egyptian blue, is 10 times more fluorescent than previously thought.

It could thus be used to boost energy efficiency in buildings by cooling rooftops and walls while also enabling the solar generation of electricity via windows, the authors say. Fluorescence is the emission of light from an object as a result of bombardment by other kinds of light or electromagnetic radiation. Previous research has shown that when Egyptian blue absorbs visible light, it subsequently emits light in the near-infrared range.

Considered to be the first synthetic pigment, Egyptian blue—which is derived from calcium copper silicate—was routinely used on ancient depictions of gods and royalty in ancient Egypt. It was known to the Romans as "caeruleum," but after the Roman era the pigment fell from use and the manner of its creation was forgotten until the 19th century.

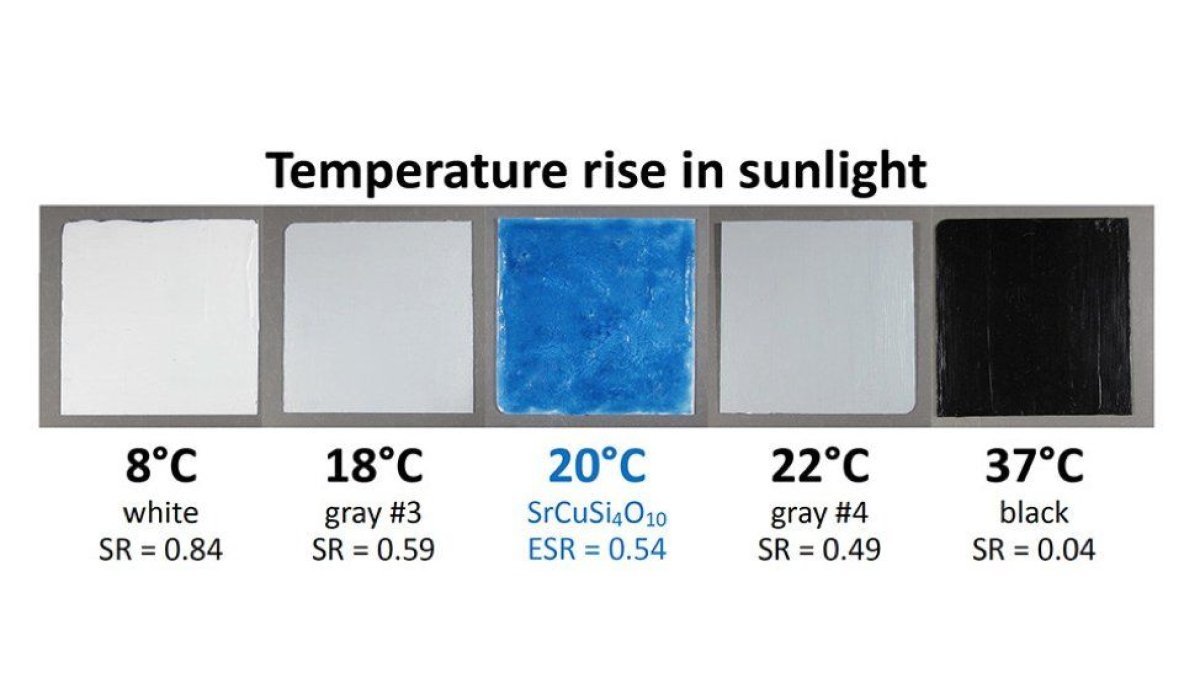

For their study, the scientists coated sample surfaces with Egyptian blue and related compounds and exposed them to sunlight, measuring the temperature afterward. They found that fluorescent blues can emit nearly twice as many photons—or particles of light—as they absorb.

The latest findings bolster our understanding of which colors are most effective for cooling rooftops and facades in sunny climates. While white is the most conventional and effective choice for keeping a building cool by reflecting sunlight and reducing energy use for air conditioning, building owners often require nonwhite colors for aesthetic reasons.

Berkeley scientists have previously shown that fluorescent ruby red pigments can be an effective alternative to white. Now, Egyptian blue can be added to the list of cooling color choices.

As well as its potential to cool buildings, the fluorescence of Egyptian blue could also be harnessed to generate energy. If solar cells are applied to the edges of windows tinted with the blue pigment, they could convert the high quantities of reflected near-infrared energy to produce electricity.

Reflective roofs and walls can cool buildings and cars. This would mitigate the urban heat island effect and reduce the need for air conditioning, which uses large amounts of energy and thus contributes to the burning of fossil fuels—a driver of global warming. By reflecting the sun's rays back to space, these cool materials also release less heat into the atmosphere, thus helping to cool the planet and offset some of the effects of warming.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.