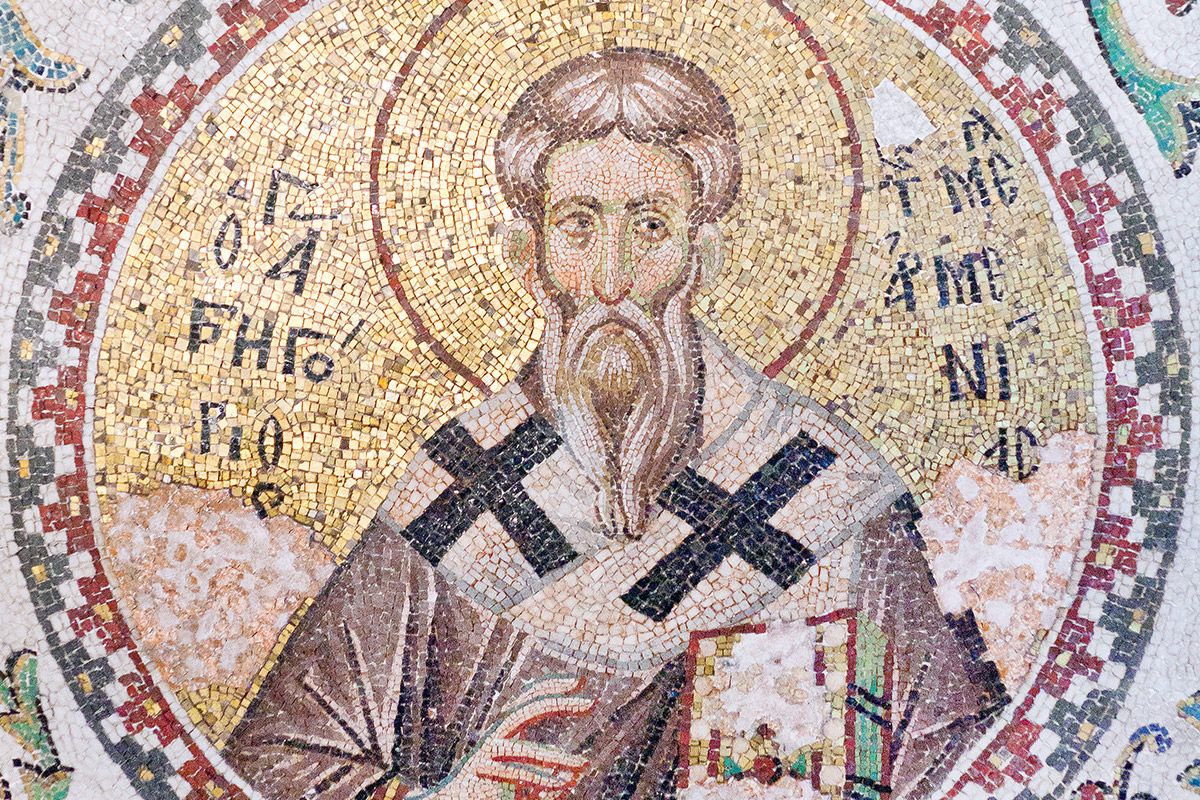

An ancient, 1,500-year-old pile of trash has given archaeologists insight into the downfall of the Byzantine Empire.

To uncover what may have contributed to the decline of the Byzantine Empire, researchers studied mounds of garbage in the ancient outpost city of Elusa, in the Negev Desert in Israel. The authors of the study, published in the journal PNAS, found that the disposal of refuse stopped around a century before the empire collapsed.

Past research has tied Islamic conquests to the unraveling of the eastern section of the Roman Empire. But the new research dates this to around 100 years earlier than previously thought, and implicates climate change and disease.

Organized trash collection and its decline in the urban settlement of Elusa showed a pocket of society was falling into crisis at a time when the Byzantine Empire as a whole was stable and trying to expand, the authors maintained.

Guy Bar-Oz, lead author of the study and professor of archaeology at the University of Haifa in Israel, told Live Science: "Instead, we are seeing a signal for what was really going on at that time and which has long been nearly invisible to most archaeologists—that the empire was being plagued by climatic disaster and disease."

About seven small village settlements centered on the adminstrative center of Elusa, as well as farms farther out, the authors wrote. The bustling city featured public spaces, such as a gym, theater, public baths and churches.

And while architecture in a city provides a certain level of insight into how people lived, it can be complex to study because it was occupied and at the center of city life. In comparison, landfills are more constant and untouched.

"For me, it was clear that the true gold mine of data about daily life and what urban existence in the past really looked like was in the garbage," Bar-Oz told Live Science.

The researchers excavated and analyzed several mounds of trash in the settlement. "These reveal the massive collection and dumping of domestic and construction waste over time on the city edges," the authors wrote.

Lying in the mounds were items including pieces of ceramic pots, seeds and pieces of charcoal. Olive pits and luxury foods imported from the Red Sea and the Nile River were also discovered, Live Science reported.

By assessing the artifacts, including by performing carbon dating tests on seeds and the pieces of charcoal, the archaeologists concluded that the mounds had existed for about 150 years. It also enabled them to calculate a date for the cessation of trash removal: the mid-sixth century.

This was around the time of the Late Antique Little Ice Age: a period of cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, which followed three volcanic eruptions, as well as the outbreak of the Justinian Plague in A.D. 541. By its end in 590, it had wiped out 100 million people.

The settlement's inability to maintain a trash disposal service, the researchers argued, indicated the society could not cope with rapid climate change and the pandemic.

Benet Salway, a senior lecturer in ancient history at University College London who was not involved in the research, told Newsweek: "It applies only to one site, which may not be representative. After all, as noted in the study, this was an area (the Negev) that flourished for a period, and was arguably always economically marginal, so that the 'decline' might simply be a reversion to the status quo ante A.D. 350."

This article has been updated with comment from Benet Salway.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kashmira Gander is Deputy Science Editor at Newsweek. Her interests include health, gender, LGBTQIA+ issues, human rights, subcultures, music, and lifestyle. Her ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.