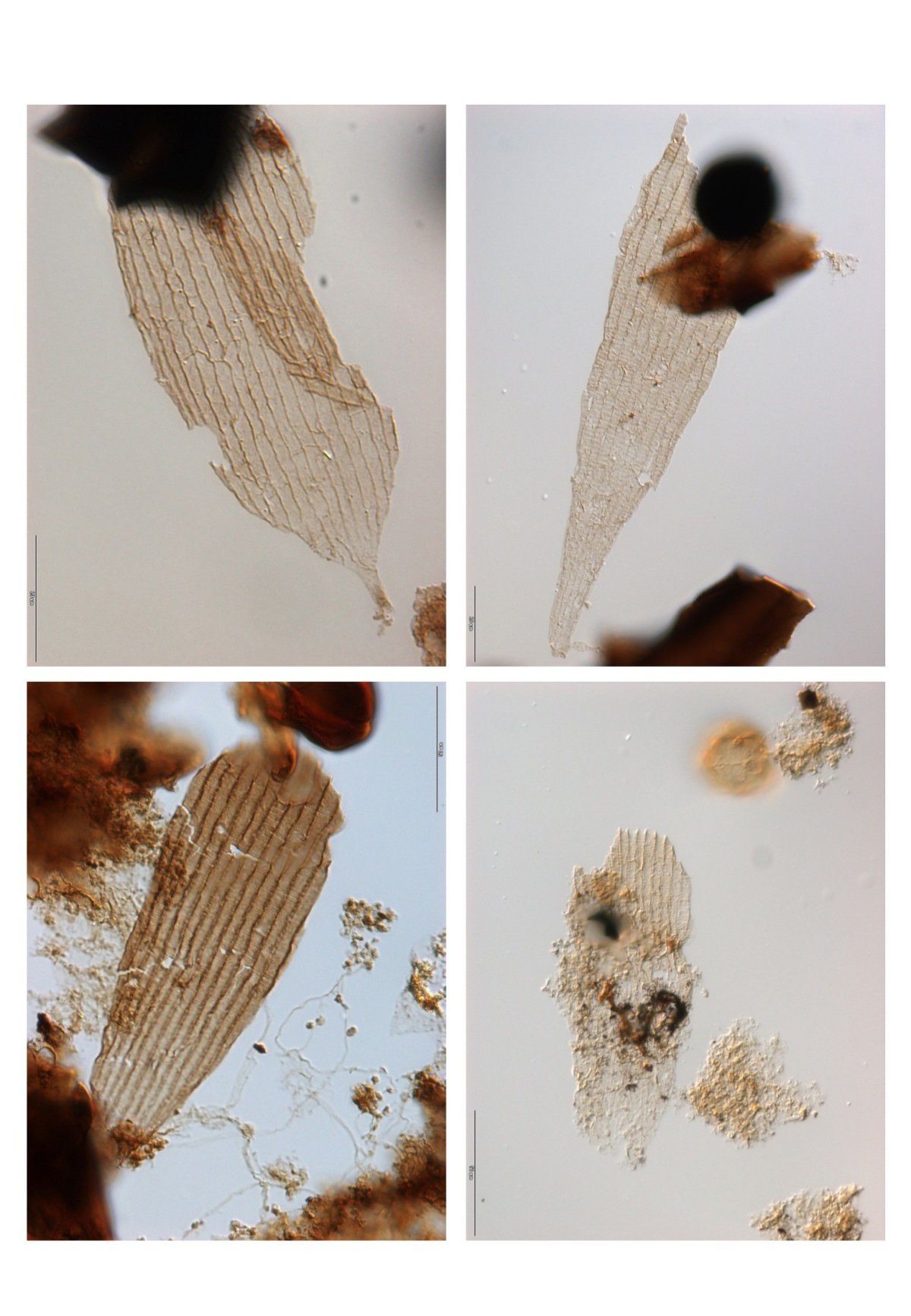

From within rocks, a few dozen fossils nearly too small to see with the naked eye can tell an important history of the evolution of moths and butterflies.

About 200 million years ago, an ancient member of the insect order Lepidoptera, which includes butterflies and moths, flew among dinosaurs. As insects don't have bones and are very delicate, it's difficult and rare for them to fossilize. But scientists have found the tiniest remnants of one of these flying insects—wing scales.

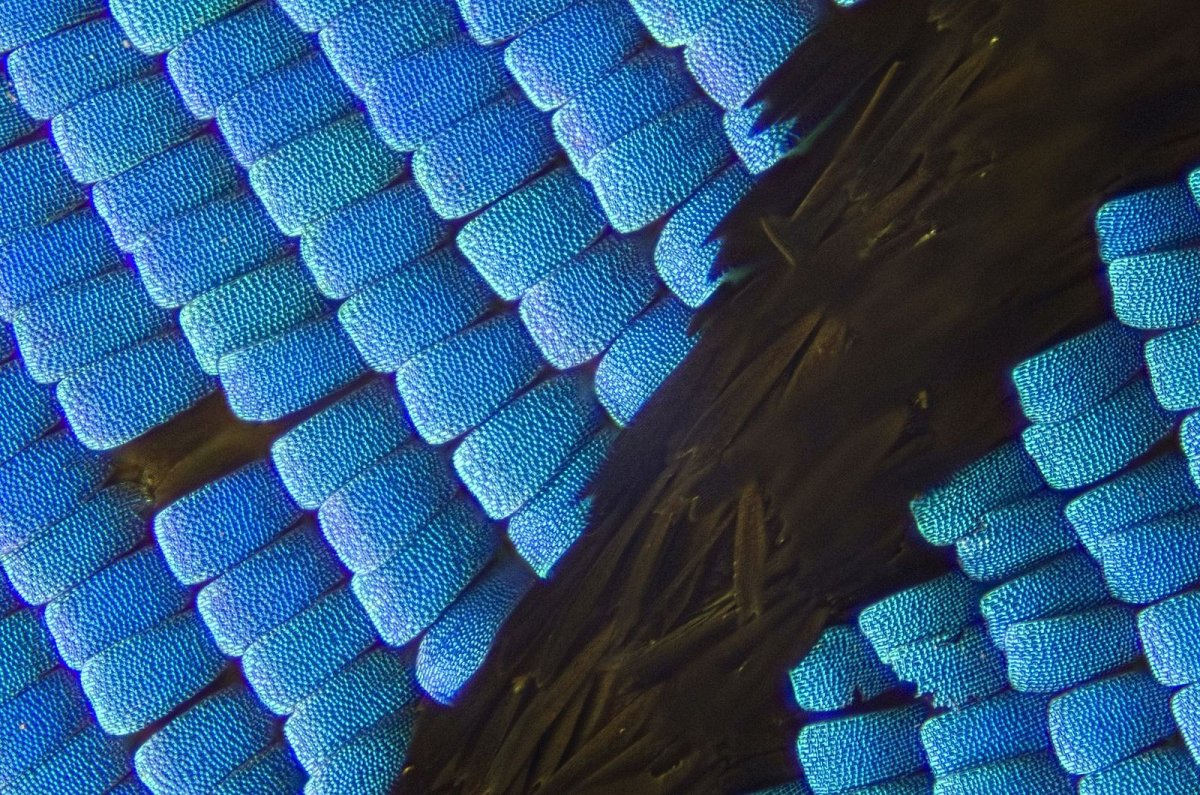

You may have to use a microscope to see them, or at least a camera with a macro lens, but moth and butterfly wings are covered in scales. In butterflies, these scales produce vivid colors, and butterflies and moths both can evade capture from spider webs by shedding their scales when they become tangled.

Entomologists look at these scales in detail and know which kinds of species have which kinds of scales. Researchers studied about 70 wing scales, and parts of scales, from the 200-million-year-old rocks and compared it with modern moths and butterflies. Research on the new fossil was published today in the journal Science Advances.

What they found surprised them. They looked most like the wing scales of moths in the suborder Glossata, which is characterized by the long, coiling appendage on their faces. This "proboscis" unfurls like a flexible silly straw to suck nectar out of flowers. The authors of the paper suspect that since the scales on the wings look just like the members of this group, the ancient species from the fossils might be a member as well, hosting the characteristic curled-up drinking tubes on their faces.

However, this grouping raises another question. What did these animals do with their proboscis? Two hundred million years ago, there were no flowers to feed from. So what was the point of evolving something specialized that can only suck up liquids?

The researchers have another hypothesis: perhaps they sucked pollination drops from ancient gymnosperms, which are a group of plants that excrete a type of high-energy liquid that's an ideal snack for insects.

This changes a lot of what we know about butterfly and moth evolution. First, it pushes back the timeline for the Lepidoptera order by 50 million years; we had previously thought that the order was only 150 million years old. Furthermore, if the scientists are right, it means that the butterfly and moth family didn't evolve their proboscis to feed from flowers specifically, but that the appendages came in handy later when flowers evolved.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kristin is a science journalist in New York who has lived in DC, Boston, LA, and the SF Bay Area. ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.