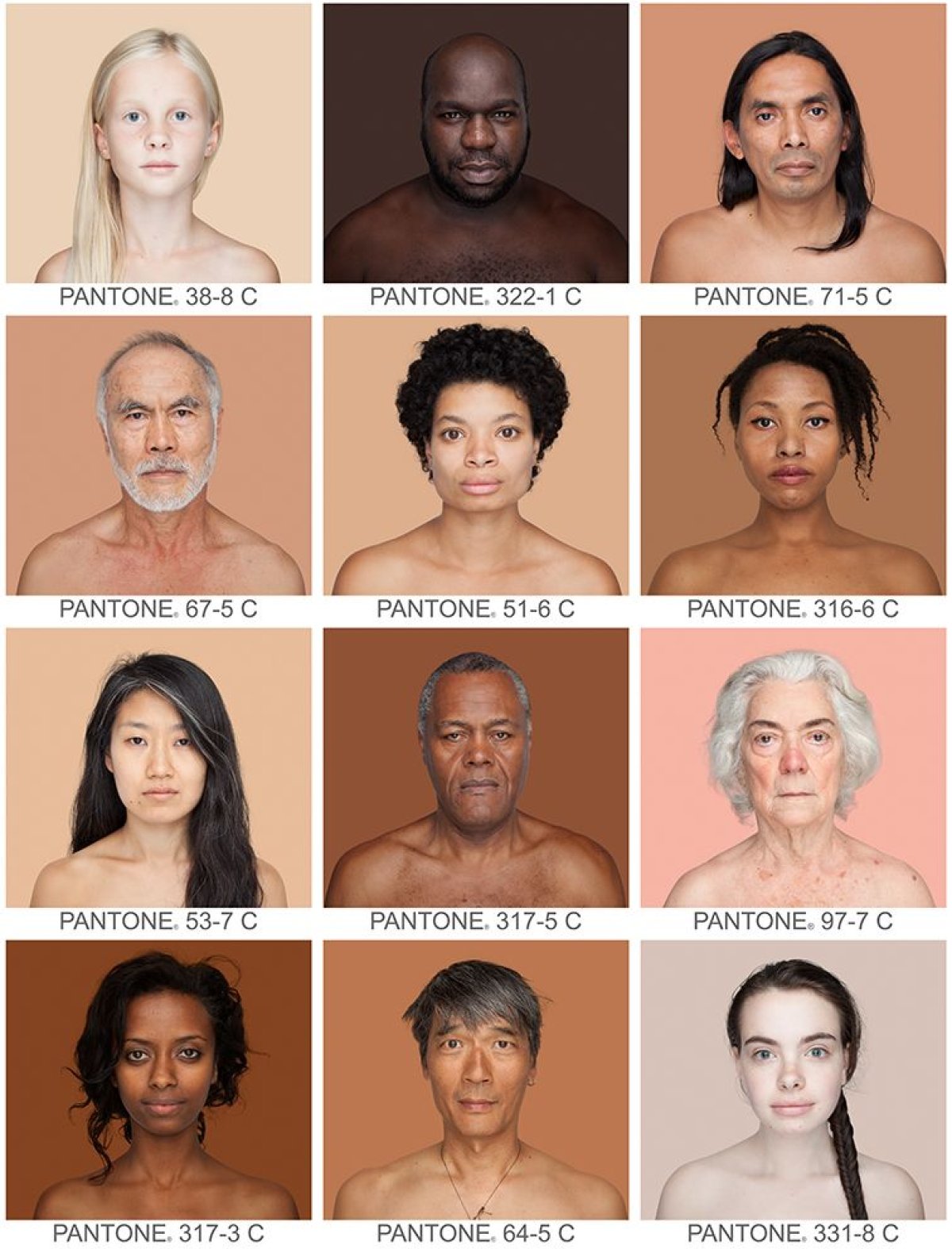

Angélica Dass is wide-eyed, gesturing excitedly with one hand while thrusting forward a grid of four photographs with the other. In each, a human face stares out, all hailing from different parts of the world, of different ages, from different walks of life. Yet each has something in common: their skin tone. For all four, it's listed as "58-6c," a shade of cool peach. "There are four persons that in theory have the same...color," she says, "but of course, talking about the stereotypes, they are 'Asian,' they are 'Moroccan,' 'the posh girl.'"

"Let's look how we judge the world," she continues. "How we construct...these stereotypes, around these four people. It's not just color, definitely."

Dass is a photographer based in Madrid, part-artist, part activist. For her Humanae project, she is documenting every human skin tone through portrait photos, each of which she assigns a color taken from Pantone's standardized guides, used by designers worldwide since the 1960s. In so doing, she highlights the absurdity not only of racial discrimination, but of traditional concepts of race too.

She has exhibited her work around the world, including in the entryway of the World Economic Forum at Davos ("I'm not sure if [British Prime Minister] Theresa May agrees or not with me, but she had to enter and see my photos," Dass says proudly.) Wednesday marks the opening of the work's first appearance in London, as part of the No Turning Back exhibition at the city's fledgling Migration Museum, while in October Humanae will open in the U.S., in Kingsport, Tennessee.

Humanae will never be a finished work. Dass can never photograph everyone in the world, let alone capture each of their skin tones as they appear in summer and winter, drunkenness and sobriety. That is part of the point. "People ask 'oh, how many colors [do] you have?'," she says. "I have no idea, I really don't care."

Dass uses Pantone's spectrum partly because of how easily it communicates her central message: "For example, when I've been in a favela in Rio [photographing] someone that barely can read, when she looks at that image and that number," Dass says, "she was able to understand." The work's power lies in the aggregate of the photos, many of which which are visible online as a multicolored mass of humanity. "Using this scale, I am sure that nobody is 'black,' and absolutely nobody is 'white'... these kinds of concepts that we used in the past are completely nonsense," Dass says.

Exposing that "nonsense" is a personal mission for Dass, or at least began as one. Born in Brazil, she says she would be racially classified by many in that country as "Pardo," a category of usually dark-skinned people of mixed ethnicity (Dass's own skin tone in her Humanae self-portrait is "7522 C" according to the Pantone scale, a brown shade of middling depth.) "I never had a doll that looks like me, for example, when I was young," she says, and understood early on the narrow range of skin tones represented in mass media.

Later, she worked in fashion magazines, but came to realize that "I never see myself, even in the images that I'm creating." She points out that if aliens came to Earth, they would get a deeply inaccurate picture of humanity from any analysis of mainstream media. Her work, incomplete as it is, would offer a much better-rounded research opportunity for extraterrestrials.

The alien visitor might just be a hypothetical. But there are people here on Earth who seem not to grasp the message of Dass's work. U.S. President Donald Trump, with his antipathy toward refugees and Islam, his tepid and qualified condemnation of white supremacist groups, and the racist statements about Mexicans that won him such attention during the presidential campaign, is one high-profile figure who doesn't sign up to such a pro-diversity world view.

If Newsweek could bring him along to one of her shows, Dass would "not make any special speech" for Trump (Disclosure: Newsweek definitely does not have this power), but would be willing to engage him in debate as she has people with skin tones across the color range who disagree with her egalitarian vision.

On the other end of the political spectrum, how does she see her art and activism squaring with that of a group like Black Lives Matter, which chooses not to talk about "all lives" but instead focuses on particular racial groups who experience specific disadvantages? "I believe that we have different kind of activism," Dass says. "I look what you call black but I always said that I am half African heritage, I am proud to have European heritage, I am very proud to be native Brazilian, so I don't want to choose one part of me and fight against it."

"I respect all other kinds of activism," she continues. "I believe that they are necessary, each one; choose yours. Because Malcolm X was as important as Martin Luther King, having completely different ways to approach the same issue."

Dass namechecked King in a TED talk she gave in 2016, too: "It has been 128 years since the last country in the world abolished slavery," she says, "and 53 years since Martin Luther King pronounced his 'I have a dream' speech. But we still live in a world where the color of our skin not only gives a first impression but a lasting one that remains." Humanae is not the most complex artwork to tackle the subject of race. But the stark and emotive point it makes about the absurdity of racism's persistence in 2017 makes it worth taking the time to stare at.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Josh is a staff writer covering Europe, including politics, policy, immigration and more.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.