The family of Anne Frank—a Dutch Jewish girl who became arguably the most famous victim of the Holocaust—tried to escape to the U.S. but were foiled by America's slow-moving and restrictive immigration policy, researchers have discovered.

The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum said the Frank family's failure to secure passage to the U.S., and later Cuba, forced them to go into hiding in Amsterdam as Nazi troops occupied much of Western Europe, the Associated Press reported.

Anne's father Otto tried to secure application papers for American visas twice before his family retreated to their famous attic hideout on July 6, 1942. As the Netherlands was brought under the heel of German occupation, Otto wrote to a friend in the U.S. saying, "I am forced to look out for emigration and as far as I can see USA is the only country we could go to."

Researchers believe his transatlantic escape efforts began as early as 1938. In a 1941 letter to friend Nathan Strauss, Otto Frank said he filed an application at the American consulate in the port city of Rotterdam in 1938.

By then, the dark clouds of war were already gathering over Europe. That year, the Anschluss annexed Austria into Hitler's Reich, and German-speaking regions of Czechoslovakia were surrendered to the Nazis by British and French leaders. In Germany, the Kristallnacht riots—also known as the Night of Broken Glass—killed at least 91 Jews as mobs rampaged through communities across the nation, destroying Jewish homes and business.

The Frank family remained on the immigration waiting list until May 1940, when the German invasion destroyed the consulate and all documents inside.

Hundreds of thousands of people were trying to flee to the U.S. as Europe slid into one of history's bloodiest conflicts. But following decades of post–World War I isolationism and with the pressure of a strong interwar "America First" lobby, only 30,000 U.S. visas were being issued annually.

The application process itself was laborious and could take several years. Even after satisfying demands for stacks of paperwork and affidavits from relatives or friends in the U.S., applicants could still be refused.

On top of all this "there was limited willingness to accept Jewish refugees," the Anne Frank House press release said. The U.S. turned away 900 German Jews aboard the St. Louis passenger ship when it fled Germany in 1939. The passengers were eventually settled in a range of European countries, though many ended up murdered in concentration camps as their hosts were overrun by the German war machine. American authorities also rejected a proposal to allow 20,000 Jewish children to travel to the U.S. for safety.

Related: One-third of Americans don't believe 6 million Jews were murdered during the Holocaust

Otto Frank tried again months before going into hiding, but the war had closed all American consulates in German-occupied territory. He also sent an application for a Cuban visa, but it never came through.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor, in 1941, all transatlantic passenger shipping was suspended, leaving the Franks and millions of other Jews stranded in Nazi Europe.

Though not actually rejected by American authorities at any point, the researchers argue that the Franks "were thwarted by American bureaucracy, war and time." Annemarie Bekker of the Anne Frank House added: "All their attempts failed, so going into hiding was their last attempt trying to get out of the hands of the Nazis."

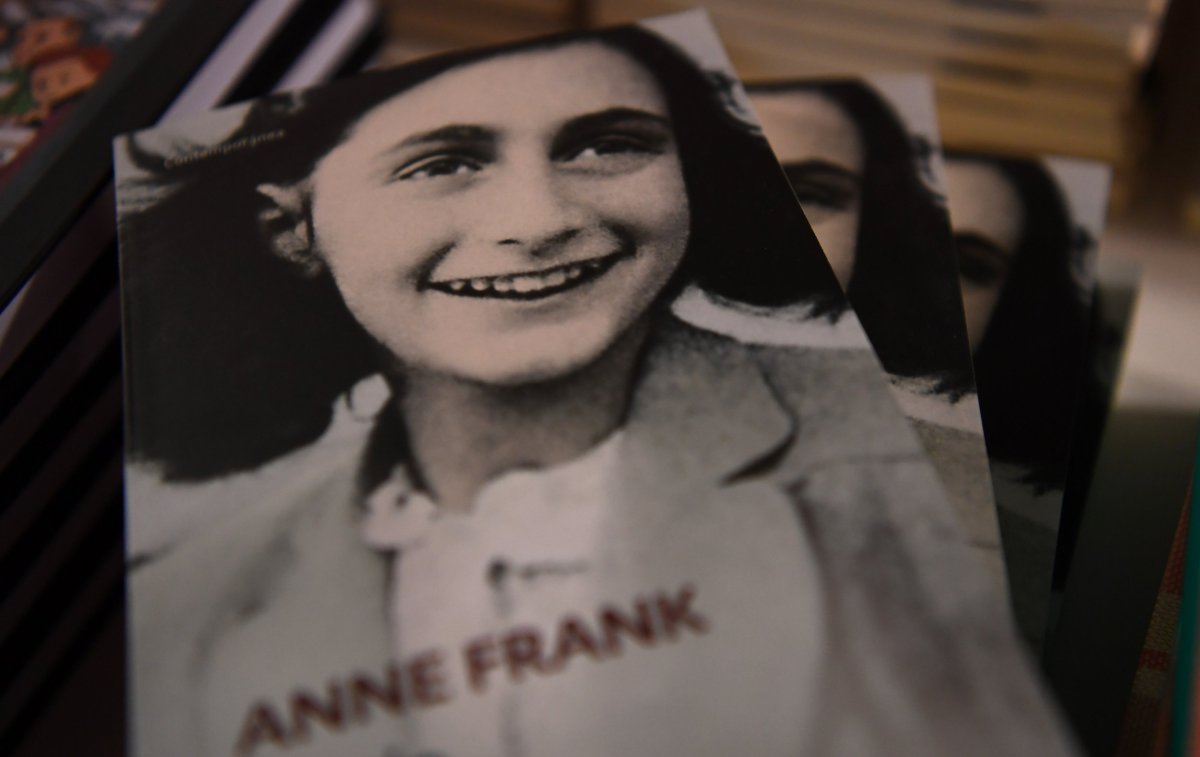

Anne Frank wrote her famous diary as the family spent two years holed up in a tiny Amsterdam attic. They were discovered on August 4, 1944, and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp. Anne and her sister, Margot, were later transported to the Bergen-Belsen camp, where both died just weeks before the camp was liberated. Margot died at age 19, followed days later by 15-year-old Anne. Their mother Edith starved to death at Auschwitz in January 1945.

Otto was the only survivor. He worked to publish Anne's writings as a testament to her memory and a symbol of the human cost of the Holocaust, in which as many as 15 to 20 million people may have died, including 6 million Jews.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

David Brennan is Newsweek's Diplomatic Correspondent covering world politics and conflicts from London with a focus on NATO, the European ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.