In all mythic, transformational trips—acid, ayahuasca, Mars or across the river Styx—the voyagers must, at some point, face down their deepest fears. For expeditions into Antarctica, the most deeply strange place on Earth, the Drake Passage is where that happens.

This tumultuous realm—where the Pacific and Atlantic oceans converge at a latitude where water unimpeded by land flows in a continuous circle around the globe—was first sailed by Sir Francis Drake, the storied 16th-century English naval explorer. Winds and swells in the passage are commonly "hurricane" on the Beaufort scale. Its harrowing reputation prompted a 19th-century theory that the Drake Passage was a planetary drain leading to the South Pole, a notion Edgar Allan Poe used to terrifying effect in his short story "MS. Found in a Bottle," in which a cargo ship passenger narrates the destruction of his vessel and the events before his death.

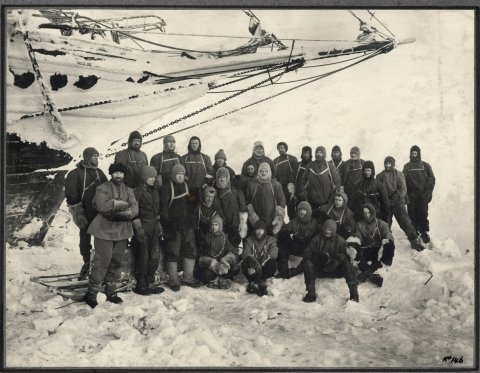

The Drake is not a drain, but it has sucked down more than 1,000 ships and countless sailors in the four centuries since men started crossing it, lured by dreams of ice and adventure. According to lore, in 1914 over 5,000 adventure seekers responded to an ad that Ernest Shackleton placed in a London newspaper for something called the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition: "Men wanted for hazardous journey, small wages, bitter cold, long months of complete darkness, constant danger, safe return doubtful. Honour and recognition in case of success." The text of that advertisement might be a myth, but what is certain truth is that Shackleton handpicked 28 applicants from a large and eager pool to accompany him. They, plus packs of sled dogs and a ship's cat, set sail from Plymouth on August 8, 1914, on a ship called the Endurance, aiming to become the first men to traverse Antarctica on foot.

The venture quickly turned calamitous. The Endurance safely crossed the Drake, but when it hit the ice-strewn water around Antarctica, things went very, very wrong. The ship sailed to within 80 miles of the Antarctic coast before it got stuck in pack ice—vast, thick floes that form on top of the ocean and move with the currents and winds. In February 1915, pack ice was pushing against the Endurance. By then, the ship was way off schedule, and the men knew they would not be marching across the continent anytime soon. Rather, they watched helplessly as the ice slowly crushed the Endurance into kindling.

For 16 months—four in the complete darkness of the Antarctic winter—the men and their sled dogs lived on an ice floe in canvas tents and slept in reindeer fur bags, surviving on melted snow, a small daily ration of lard and dried meat, as well as, occasionally, seal or penguin meat. As the Antarctic summer came on, the ice beneath them softened and began to split, and in April 1916 the men were forced to abandon camp (after mercy shooting their sled dogs, puppies and camp cat). With ice cracking under their feet, they flung themselves into small lifeboats and rowed for seven harrowing days to a speck of terra firma called Elephant Island.

Realizing his men would die there if they didn't move quickly, Shackleton chose five to accompany him on a last-ditch effort to get help. They crossed the dreaded Drake yet again, this time in one of the open lifeboats with the crudest navigational device, enduring another two weeks of ice and storms at sea, before landing at South Georgia Island, then hiking for 36 hours over a mountain range to a whaling station. When they finally reached the outpost of civilization, children ran from the sight of the men with faces black from many months of seal-blubber smoke, and hair and beards down to their chests. Months later, Shackleton managed to find a boat strong enough to get through the ice to Elephant Island, and he rescued the rest of his men.

That expedition was the last in what's called the Heroic Age of Exploration, when many raced to Antarctica, the final unexplored continent, in the name of commerce and empire, vying to be first to see what could be seen and take what could be taken. Today, the Antarctic is being prospected yet again. But these days, the continent's explorers are a different breed: men and women of science who are looking not for commodities but for answers to some of the most pressing questions facing humankind.

The history of the planet is held in frozen suspension in the Antarctic. What we can see of the continent with our eyes—vast, nearly lifeless, an otherworldly expanse of blue and white—is a fraction of the story. Vertical miles of ice encase air bubbles that hold bits of atmosphere of a truly ancient vintage, some dating as far back as a million years ago. Fossil records show the place was once green, teeming with life and connected to the great Pangea land mass before it broke off from what would eventually become Australia and the Indian subcontinent, and moved south. Isolated by the encircling frigid sea, it became the world's refrigerator, with 90 percent of the planet's ice (and 70 percent of the world's freshwater) atop just 10 percent of its land mass.

But those 7.2 million cubic miles of ice are now melting at unprecedented rates. If they were ever to melt completely, sea levels would rise nearly 200 feet. That worst-case scenario probably won't occur, but the Antarctic Peninsula is already warming at a rate five times faster than any place on the planet. Scientists have predicted that even partial melting of the Antarctic ice will raise sea levels enough to force the 150 million people around the world who live 3 feet or less above the sea—including parts of New York City, Miami and Mumbai, India—to abandon their homes. It would destroy harbors and ports, and trigger a cascade of environmental catastrophe, ruining wetlands and decimating the ecology of the world's watersheds.

Uncovering the history stored in that Antarctic ice could help scientists understand exactly how much ice will be lost and when the sea will rise. That's why it attracts researchers from a variety of different countries—many of which, Russia and the United States and China, for instance, are not on particularly warm terms anywhere else. Under the International Antarctic Treaty, the nations have collectively agreed to leave Antarctica unclaimed. Some clearly hope to eventually control and harness resources like freshwater and seafood, but the agreement on Antarctica's protected status went into effect in 1998 and will remain in place until 2048. So for now, it's essentially a giant Earth sciences lab.

Taxidermy and Mango Panna Cotta

If you're not a scientist with access to a cargo plane taking off from New Zealand, the only way you're likely to see Antarctica is by crossing the Drake aboard one of the 31 passenger ships and 20 charter yachts that ply these waters in the summer months. About 35,000 people annually take a ride on one of these ice-cutting ships, which are heavier than other seacraft, designed with specially curved steel bows, powerful engines and propellers made to work in ice.

Modern technology has changed almost everything about Antarctic travel since the great age of polar exploration, but it cannot alter the way the human body reacts to the untamable Drake. One stormy night during our crossing, while I was pinned to my bed by the bucking ship, trying to subdue the gray-green worm of seasickness slithering around my torso, my cabinmate, Charlie Wittmack, leaped up in the dark and snatched a trash can. Wittmack is a seasoned explorer who has survived malaria, a broken back, cerebral edema and more on prior expeditions. If the Drake Passage could fell him, it didn't look good for me. And indeed, for the next 24 hours, I lost all sense of boundary between my body and the motion, as 30-foot swells sent us on carnival-ride plummets through the air three or four times a minute.

By the second morning out of South America, the sea calmed and shouts of "Land ho!" went up as we spied some of the islands north of the Antarctic Peninsula. We donned parkas and life jackets and boarded Zodiacs, small, black, heavy-duty rubber motorboats that sit low enough in the sea that one can touch the broken ice clicking and hissing in the 28-degree water. If you fell in, you'd survive four minutes, max. The Zodiacs pulled in close to humpback whales and penguins, but we couldn't go near the fantastic icebergs looming in the distance; though they seem serene and inviting with their radioactive-blue glow, they're dangerously unstable, liable to shatter without warning, sending giant shards falling into the sea.

The man behind the zany idea of plopping landlubbers into rubber dinghies in the Antarctic Ocean was an eccentric Swedish world traveler named Lars-Eric Lindblad. In the early 1960s, Lindblad was leading a band of jet-setters across the Mongolian desert when he decided it was time to take tourists down to Antarctica. He had never been there, but he borrowed a transport vessel from the Argentine navy, which helpfully tossed in an Antarctic tug and ice breaker, and he sold his first trip to 56 passengers. The tour was straight out of a Monty Python movie, with one elderly passenger who, he later wrote, forgot her name while at the Buenos Aires hotel; a self-described "nymphomaniac" who informed Lindblad soon after boarding that she had selected the ship's second in command to help her satisfy her lust; and a woman who had a psychotic break while on the voyage, ran through the ship naked and had to be restrained in her room and spoon-fed by fellow passengers for the rest of the journey.

The ship carrying us, the National Geographic Explorer, is an ice-cutting, refurbished Norwegian coastal ferry, owned and operated by Lindblad Expeditions, under the stewardship of Lindblad's son Sven, who runs the company as a sedate, profitable, conservation-minded enterprise. He has, for example, hosted on the ship an Arctic Summit attended by Jimmy Carter, and Al Gore's climate change organization chartered the same vessel for a conference in Antarctica. Typically, cabins are not cheap, starting at $12,970.

I secured my passage on the Explorer by virtue of a book I wrote about early explorers of Egypt. After it was published, I was invited to join the Explorers Club, a relic from the 19th-century New York City social scene, when bagging exotic game was not a felony and the world's far edges had not been Instagrammed. Membership leans gray and male, and it has a venerable pedigree. Polar explorer Robert Peary's sledge hangs from the rafters above the lecture hall in the club's Upper East Side headquarters, and lunar astronauts occasionally show up to tell tales among the narwhal tusks, taxidermied cheetahs and lions. At Explorers Club events, Wittmack and I had discussed what exploration means in an era when most of the world has been named and mapped. An opportune moment to find out arose when representatives from Lindblad Expeditions, whom I had met through the club, invited journalists and artists on an Antarctic tour to mark the centenary of Shackleton's trip.

We flew to Buenos Aires and then took another flight on to Ushuaia, Argentina, where we boarded the Explorer and followed the Beagle Channel (named after Charles Darwin's legendary ship), leading out past Cape Horn. Our shipmates on the Explorer were a band of middle-aged world travelers and wealthy retirees, many ticking off their seventh continent or working through a bucket list. One intrepid ice lover had been to Antarctica four times; another was celebrating a 50th birthday. A gaggle of elegant, gray-headed Vassar and Smith alumnae were on board as part of a trip organized by the alumni association. One woman was in a wheelchair, on oxygen. Some passengers were so old they could barely walk on land, let alone in the pitching boat. The 3-year-old daughter of one of the ship's officers rounded out the passenger manifest.

Infants and the infirm are now able to voyage to a part of the world where safe return was not assured until recently. Today, Antarctic travel includes hot showers, gym and sauna access; a sun-splashed lounge with dozens of flat-screen TVs; and shipboard Wi-Fi, enabling us to Instagram our penguin and iceberg pictures in real time. We feasted daily on gourmet meals, complete with green salads, French cheeses and desserts like mango panna cotta—gluttony unimaginable to the polar explorers of yore but perhaps justifiable, given that, as Gabrielle Walker wrote in her evocative book on modern Antarctica, life here is "survival not of the fittest, so much as the fattest."

The biggest draw of the Antarctic, though, is its growing fragility. Leaving New York in late fall, the weather was freakishly warm, an effect of a particularly strong El Niño exacerbated by unusually warm Pacific Ocean waters. International leaders and environmental advocates were descending on Paris for COP21, the climate conference to address the reasons behind global warming and catastrophic polar ice melt, and on board the Explorer there were lectures on climate change. "A lot of people come to the polar regions because climate change is such a feature in our news," says the ship's "expedition leader," Lisa Kelley, who travels to both the north and the south polar regions every year. "Often we hear people say, 'Oh, we want to go there before it's gone.'"

A Taste of Penguin

Our landings were closely supervised to limit the risk of ecological impact. The minute we set sail from Argentina, we signed a form promising not to bring anything onto Antarctic shores other than our scrupulously vacuumed clothes and sanitized boots. A PowerBar or stick of gum would have gotten us banned from future hikes, and, we were told, environmental lawyers up north had nothing better to do than examine social media photographs from tourists, looking for treaty violators hugging penguins and baby seals.

The Zodiacs took us ashore first on Half Moon Island, a curve of black pebble beach set against mountains layered with whorls of snow. The reflected sunlight was blinding, and the smell of penguins reminiscent of back alleys strewn with shrimp shells in New Orleans. Our first penguins! Oh! Cameras started clicking as the iconic, chicken-brained creatures waddled among our legs. They were oblivious to us and on a mission, each selecting a single beach pebble to carry in its beak uphill to a rookery, making stone nests for their pale-blue eggs. It was a task they managed with great dignity, walking hundreds of snowy yards up and down the mountain like old men in an old country doing something the hard way simply because that's how it's always been done.

These cute creatures saved the lives of some stranded polar explorers of earlier times, who ate them and thereby not only avoided hunger but also recovered from scurvy (penguins, like oranges, contain vitamin C). Today, no one seems to know—or will admit to know—how penguins taste. The last documented penguin meal occurred on a scientific expedition in the 1960s. An early 20th-century writer described the flavor as duck and beef cooked in cod liver oil and blood.

We were instructed to remain at least 15 feet from these birds (though as long as they approached us, we were not at fault). We were also told to stay on the path marked by orange cones—if we strayed, we might end up poking holes in the snow as deep as our knees, into which a penguin could fall, get stuck and die. The environmental micromanagement was poignant. This was, after all, one of the islands where humans by the early 19th century had hunted fur seals into near extinction, and in waters around us, as recently as the 1960s, Russian and Japanese whalers harvested a giant whale—usually humpback—every 22 minutes. But it also felt incongruous that a single hole in the snow could be an ecological crime in a place where one of the greatest ice shelves on the planet is melting thanks to our power plants and cars, not to mention the portion of jet fuel we had each burned to fly down here to snap photos of icebergs and penguins.

By the third day out of Cape Horn, we were below the 66th parallel—the Antarctic Circle—and nosing in and around bays and coves with names like Exasperation Inlet and Cape Disappointment. Every morning, we woke up to stranger and stranger landscapes: It is still on Earth, but Antarctica is very much alien land. In his book The Future of Life, Nobel-winning American biologist Edward O. Wilson wrote of Antarctica, "On all of the Earth, the McMurdo Dry Valleys most resemble the rubbled plains of Mars." Antarctica is not quite as uninhabitable as Mars, but almost. Human life is supportable there only with generators and heated stations, and all food and supplies must be brought in during the summer and stored for use over the winter months, when there is no way in or out.

It's a place that tricks the eye, a natural trompe l'oeil. On land, the whites stretch on forever, and snow, peak and cloud mingle so voyagers lose track of the difference and distance is impossible to gauge. At sea, icebergs loom out of the fog, looking like cubist Gothic castles or an abstract Sphinx. And there are not enough words in the English language for the many shades of blue here, just metaphors alluding to the Caribbean Sea, the unstable edge of the periodic table or my newly frozen lips.

In this odd realm of in extremis, explorers have reported uncanny experiences. After their ordeal, Shackleton and his men confessed that they had all sensed the presence of a "fourth man" —an unseen someone alongside them the whole time. It wasn't the first such encounter, nor the last. The snow and the physical and psychological hardships of the Antarctic can cause hallucination, even in the strongest of men and women. In 2012, polar explorer Felicity Aston became the first woman to ski solo across the Antarctic continent. At some point during her 63 days alone, she started talking to the sun — and it talked back. Eventually, she had entire conversations with it. "The scariest thing I realized was I couldn't rely on my own mind and my own sense," she has written. She later asked a sports psychologist whether she ought to worry about going crazy. The psychologist replied that as long as she knew what was real and not real, she was fine. Aston, a climate scientist by training, concluded, "There are different layers of self-perception. I got a glimpse at just how complicated the brain can be."

Reporting Back to Rush Limbaugh

These days, radar, sonar, satellite images and the benefit of a century of science can help ships' captains and crews predict the movement of ice, so the majority of tourists on "expeditions" face almost none of the challenges that beset the explorers of yore.

Of course, Antarctica still attracts a certain breed of daredevil—those who go well beyond the orange cone–ringed paths we took. There are, for example, the mountaineers who aim to climb the highest points on all seven continents; they wait years to get a permit to climb the 16,050-foot Vinson Massif, the highest peak on Antarctica, so remote the flight to the base alone costs $28,000. And beginning this month, British military advisers are overseeing the Antarctic Endurance 2016, a six-week sailing and mountaineering expedition in the Weddell Sea and on South Georgia Island that aims to "stand on the shoulders of Shackleton to inspire a new generation of sailors and Marines" and study the challenges of making decisions in a "real-world, arduous military training environment."

But the Antarctic explorers today that most closely share the spirit of Shackleton's explorers are the men and women doing science on and around the continent. The National Science Foundation runs three American bases—Palmer, McMurdo and Amundsen-Scott—and 30 other nations operate 70 more bases, with around 4,000 men and women working in Antarctica during the summer season. One thousand of them—the extra-hardy—over-winter there, spending four months huddled with generators in near-total darkness, enduring keening wind and epic snowstorms. Scientists in the remote field camps face great danger in any season. Supply planes can run into trouble in storms or skid into ice crevasses camouflaged by snow. Merely walking around is perilous because of the deep, hidden openings.

Then there are the polar divers, oceanographers plunging daily into the icy brine with cameras, seeking new life forms. One of these, Alyssa Adler, a 26-year-old from Portland, Oregon, works on the Explorer. "I feel like an aquanaut," she says, after spending 35 minutes pulling on the requisite gear. "By the time you are ready, you are not a person getting into the water; you are a thing in a suit, getting into a foreign medium." And when she emerges—either after she can't take it anymore or the 45-minute limit passes—her hands are stiff and frigid, she has brain freeze, and, she says, "my feet are just cold stubs."

Emerging alive from Antarctic waters is never guaranteed. In 2003, a sea leopard, a reptile-faced, 12-foot-long predatory seal at the top of the Antarctic food chain, dragged a snorkeling scientist, who was studying sea ice near one of the bases, down 240 feet, then took the corpse back up to the surface to try to eat it in front of the victim's companions. Death here is always a possibility, and discomfort is guaranteed. Those in the field don't bathe for months. Antarctic winter still drives some men mad: An Argentine base commander burned down his buildings in the 1960s when informed that the ice cutter wouldn't be able to come fetch him before winter set in, forcing the navy to rescue him.

Like the explorers competing to plant a flag at the South Pole, scientists who go to Antarctica today are responding to a global challenge, but they have a much different goal in sight. The international Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) recently ranked climate change first of 80 questions its scientists believe need to be studied in the Antarctic. On Antarctica today, they are trying to understand and predict the behavior of ice in response to human burning of fossil fuel, which has increased carbon emissions since the Industrial Revolution by a factor of 130, from 200 million tons of carbon dioxide annually to 27 billion tons today.

One of the most impressive efforts to understand what's happening to Earth is an ice coring project at one of the summits of the Antarctic ice sheet, called Dome C, where scientists drilled down 2 miles, pulling up air bubbles with atmosphere samples from 800,000 years ago. By analyzing these ancient air bubbles and comparing them with air samples from all the ice above it, scientists determined that there has almost never in history been as much carbon in Earth's atmosphere as there is now. That's helped confirm that we are in an unprecedented period of planetary warming and shifts in climate patterns.

The Antarctic Peninsula is bearing much of the brunt of those climate changes. But even so, a few days there is not enough time to "see" global warming in action; looking at all the ice, one climate change denier on the ship joked that he was planning to report back to Rush Limbaugh that "it's still really cold" in Antarctica. But animal behavior here is already changing: Some creatures are now found farther south than they used to be, seeking colder water, and some penguin colonies have disappeared. And scientists as recently as last fall predicted that a complete western Antarctic ice melt—which they say is inevitable and probably already underway—would raise sea levels by about 10 feet in a just few centuries.

Ninety-eight percent of the Antarctic continent lies beneath an ice sheet: miles-thick ice covering a vast area that has formed over hundreds of thousands of years. There are two ice sheets on Earth; the other covers Greenland. Antarctic ice is not melting as obviously or as quickly as the ice sheet in Greenland—where 80 percent of the surface ice is now melting every summer. This past November, researchers announced that losses suffered by the Zachariae Glacier in that country's northeast could open up a second "floodgate" of ice melt, joining the notoriously fast-retreating Jakobshavn Glacier in the west. But Antarctica appears to be the next to start hemorrhaging ice: Scientists are finding fragile points on the continent's western coast, where seawater overheated by global warming is slowly working its way beneath glaciers.

The weight of millennia of ice has pushed the landmass of Antarctica below sea level. Currently, only an underwater ridge is keeping one large and pivotal glacier, the Thwaites Glacier, which has been called "the weak underbelly" of the western portion of Antarctica's ice sheet, from breaking off and falling into the sea. Scientists are noticing the glacier is starting to "lose its grip" on the ridge as it melts, and once it retreats behind the shelf, computer models indicate that the warmer-than-usual seawater will rush under and around it, creating channels of flowing water that will erode the glacier from the inside out, causing it—and quite possibly the entire western Antarctic ice sheet behind it—to eventually slide into the sea.

Scientists are as certain as they can be that this will happen. What they don't yet know is when. The most pressing work in the Antarctic is to get a handle on whether this catastrophic melt is likely to happen over a long period of time or within a few decades. Their findings are of the utmost significance to every human on the planet but are particularly pressing for the hundreds of millions of people who live in coastal regions—according to one estimate, sea level rises and coastal flooding will cost $100 trillion annually in lost infrastructure and industry by 2100.

The White Bird of Guilt

For the nonscientist, there is almost nothing to see in the Drake Passage besides water. At one point, a naturalist on board the Explorer pointed out an albatross flying overhead. The legendary white bird of the Southern Hemisphere, with a 12-foot wingspan, is capable of gliding over 600 miles a day without once flapping its wings. But what immediately came to mind was the saying "an albatross around his neck," adapted from a 1798 poem by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, The Rime of the Ancient Mariner. In it, a wizened old sailor interrupts a young man en route to a wedding —and proceeds to unload a long, uncanny tale on the bewildered, then horrified wedding guest.

The mariner tells of being on a ship that drifted off course into a land of ice — the Antarctic. Eventually, an albatross flew overhead, and the mariner, for no good reason other than sport, shot it dead with a crossbow. Almost immediately, bad luck befell the ship. The crew ran out of drinking water, and the ship was becalmed. The sailors attributed this ill luck to the killing of the albatross. They later tied the bird's carcass around the mariner's neck, evidence of his guilt that he could not hide. Coleridge wrote the poem at a time when the Antarctic was still unexplored, but already commerce had churned its way down to put natural resources at the service of civilization. Whaling and sealing operations were in the process of rendering sea mammals in the Antarctic region almost extinct.

In the poem, Death plays dice for the souls of the crew and wins every roll—except one. The mariner who narrates the story is left alone on the ship, condemned to "death in life," surrounded by what he considers to be loathsome, "slimy" sea creatures. As time passes, though, he sees the animals' beauty and is filled with love for them. Rescued both spiritually and physically, having learned to love nature, the mariner travels the world carrying a message about caring for Earth and all its inhabitants.

Over 200 years later, visitors to the Antarctic return with the same message. "Basically, it changes your life," says Jenny Baeseman, a microbiologist and head of the SCAR. "Working there changed me because I no longer thought of science as something I did in my lab. I felt a deeper appreciation of the work and a desire to give back and to tell people what I learned."

For me, the spectacle had elements of the surreal travel of dreams. One afternoon, we hiked up one of the bays, where a 360-degree panorama of cream-coated peak after peak was reflected in an utterly still black sea flecked with icebergs like an ile flottante dessert. But most of all, the gorgeous, melting Antarctic Peninsula mutely testifies to the enduring relevance and new urgency of the familiar lines near the end of Coleridge's poem:

He prayeth best, who loveth best

All things both great and small:

For the dear God who loveth us

He made and loveth all.