At the annual Manama Dialogue in Bahrain, an elite Middle East security summit held in late October, the keynote speaker was Egyptian President Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi. Surrounded by a phalanx of bodyguards, General el-Sissi took the stage and addressed a packed audience of ministers, diplomats and senior U.S. State Department officials. He talked of Egypt's role in the conflicts in Syria, Yemen and Libya.

But the general's main concern—as a staunch military man who has been in the army since the age of 23—was the rise of armed factions in the Middle East. "We are concerned by the undoing of the national state and the rule of law by armed militias," el-Sissi emphasized at the gathering, just days before a Russian passenger plane went down in the Sinai Desert in what increasingly looks like a bombing by the Islamic State militant group (ISIS).

After being lauded at Manama, where he met with the German minister of defense and other bigwigs, el-Sissi flew home to take stock of the Russian airline crisis and to prepare for an official visit to Britain, where he would meet with Prime Minister David Cameron. After a period when the West was cautious about his ascent to power, el-Sissi's visit underlined the fact that he is firmly back at international diplomacy's top table, just weeks after Egypt was elected to the U.N. Security Council.

As British human rights groups were protesting el-Sissi's arrival, he told the BBC that democracy in Egypt is a "work in progress." An optimist might say the same of the whole region. A pessimist would say the trend is in the opposite direction: not more democracy but less.

Four years ago, the outlook was very different. In 2011, a trader in Tunisia set himself on fire to protest harassment by a municipal official, sparking outrage from his fellow Tunisians and protests across the region that kicked off the Arab Spring. As young Arabs took to the streets to demand freedom, there were high hopes that democracy would take hold in countries long ruled by dictators and authoritarian royal families. The 2015 Nobel Peace Prize was awarded to a collection of democracy activists in Tunisia. But to many, that looked like a desperate attempt to keep the one relatively democratic country in the region on track as its neighbors sank back into dictatorship. Egypt, above all, has disappointed those who dreamed of Arab democracy.

"If I had to mark the definitive end of the Arab Spring, it would be July 3, 2013," says Shadi Hamid, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, speaking of the day el-Sissi used the military to topple the democratically elected Mohammed Morsi and other Muslim Brotherhood leaders who had come to power through the ballot box after the Arab Spring. "When people saw the Egypt experiment failing, it had a chilling effect. It was not just about Egypt but about other autocrats playing an aggressive role in their countries."

El-Sissi's administration quickly banned protests. A month after the coup, Egyptian security forces killed nearly 1,000 protesters, most of them unarmed, in Rabaa Square. Human Rights Watch called it "one of the world's largest killings of demonstrators in a single day in recent history." Since 2013, el-Sissi has launched the toughest crackdown on Islamists in Egypt's history.

"Sissi fits the classic case of a dictator," says Jane Kinninmont, a senior research fellow at London think tank Chatham House, citing the large number of political prisoners, the ability to "disappear people" with impunity and the protesters massacred in the streets in 2013. "They hold elections, but these days there are very few dictators who don't hold elections."

It's not just Egypt. With the notable exception of Tunisia—and even there, democracy remains vulnerable, and large numbers of disaffected young men are signing up with ISIS—the Arab Spring countries have found it difficult to make the transition to a stable, more democratic system.

Syrians have endured the most suffering. A popular uprising became a civil war that descended into a bloody stalemate, with a confusing mix of rebel groups overshadowed by ISIS and Russia intervening on behalf of President Bashar al-Assad to bring further destruction through airstrikes. There is no end in sight, and Assad may yet manage to cling to power.

For the West, Libya was the other great hope, so much so that NATO intervened in 2011 to help rebels get rid of Muammar el-Qaddafi. But with the Libyan leader gone, the country fell into chaos, and Islamist militants flourished. Two rival factions claim to govern Libya—an internationally recognized government that has been banished to the eastern city of Tobruk and an alternative administration in the capital, Tripoli. As the United Nations seeks to broker a national unity government in Libya, the one man who looks increasingly powerful is General Khalifa Hifter. He has taken command of military operations against Libya's Muslim Brotherhood and other militant groups, winning the parliament's backing to "fight terrorism" throughout the country.

Hifter has shifted his loyalties over the years. He supported the 1969 coup, which toppled the old monarchy and brought Qaddafi to power. He then turned anti-Qaddafi and reportedly was trained by U.S. intelligence officers in an attempt to oust his former ally. During the Libyan revolution, he left his home in Northern Virginia to join the anti-Qaddafi forces, fighting alongside many of the militia leaders he is now attacking.

Hifter is following the Egyptian model, mimicking el-Sissi by casting all Islamists as evil, promising to crush the militias in the country's eastern portion and stressing the need to repress them to create order. "One of his calling cards is a sense of uncertainty," says the Brookings Institution's Hamid. "He is really drawing on this perception of the disintegration of order. All the strongmen are saying, 'Look what the Arab Spring has done.'"

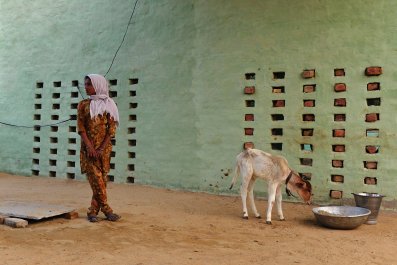

Farther to the west in North Africa, Morocco is also a cause for concern. While it has a written constitution, the country is a monarchy with no separation of powers—political, economic and religious power are all concentrated in the Royal Palace in Rabat. While King Mohammed VI has implemented some reforms since he came to power in 1999, none of them are democratic.

Arab Spring-era street protests there lost momentum, partly due to a crackdown by police, and the government has since made no moves toward greater freedom. "Democratization in Morocco is a two-way street, and right now the country is moving backwards," states a recent report on the nonprofit website Open Democracy.

On the Arabian Peninsula, things are no better. Gulf monarchies and their security forces ensured that the Arab Spring had little impact there, except in Bahrain, which has long experienced sectarian tensions since it has an estimated 60 percent Shiite majority but is ruled by the Sunni al-Khalifa monarchy. But pro-democracy protests in 2011 were crushed quickly and effectively, with the help of neighboring Saudi Arabia.

America's alliance with Bahrain, where the U.S. Navy has a vital base for its operations in the region, illustrates Washington's long-standing policy in the Middle East of putting pragmatism over idealism. "[President Barack] Obama has been silent about Bahrain," says Chatham House's Kinninmont. "It has become much more repressive. They don't pretend to be a democracy. They openly say democracy would not be appropriate in their part of the world."

Saudi Arabia, too, has long been one of Washington's closest allies, regardless of its human rights record, and Western governments seem to have accepted that they need to make similar accommodations for el-Sissi. In the spring, the Obama administration restored the military aid to Egypt that had been suspended after Morsi was deposed. The main reason for renewing aid, Obama said, was the urgent need to fund anti-ISIS governments in the region. Europe is also warming up to el-Sissi, with France increasing arms sales.

Kenneth Roth, executive director of Human Rights Watch, calls this "the lionization of the new pharaoh" and says el-Sissi symbolizes not just the return of the Arab dictator but also "the intensification of it. Sissi's repression is worse than [former President Hosni] Mubarak ever was, and the West's response of embracing him has been abysmal."

El-Sissi has said that democracy cannot be achieved swiftly in Egypt and that it takes years to build institutions that support it. "Democracy is about will and practice," he explains.

Plenty of people both inside and outside the region have concluded that democracy as enjoyed in the West is not the right fit for the Arab world. Saudi academic Majed bin Abdulaziz al-Turki of Riyadh's Center for Media and Arab-Russian Studies argues that it is wrong for Western countries to impose their views—on topics such as rights for women and minorities—on countries that do not want them. He labels such attempts "colonial."

Kinninmont says part of el-Sissi's appeal is that he has cast himself into the role of national protector and fighter against global terrorism, a tactic used by other authoritarian leaders such as Russia's Vladimir Putin, Syria's Assad and Turkey's Recep Tayyip Erdogan, as well as the Saudi and Qatari monarchs. "Some people would rather have security and be able to see their families live safely than have democracy," she says. "But that is not a cultural issue. It's a human issue."

More than a decade of chaos and sectarian violence in Iraq since U.S.-led forces ousted Saddam Hussein has only deepened that impulse. "There is a long tradition of totalitarianism in the Arab world for many reasons," says Emmanuel Karagiannis of King's College London. Countries that were historically tribal and feudal societies have perpetuated the rule of dictators and kings through state control over the media, the judiciary and security forces, as well as the oppression of women. Corruption and cronyism have flourished, and the military is generally the most powerful institution in such societies.

"Also important is that many state-controlled economies only support certain sectors that do not produce a middle class," Karagiannis says. "If you don't have a middle class, you don't have democracy."

However much human rights groups may complain, non-Arab observers are in a tough position when it comes to promoting democracy. Karagiannis says it can be dangerous for activists to accept help from the West because they can then be tarred as Western spies. Democratic change, if it comes, must come from within, he insists. "The seeds of democracy were planted by the Arab Spring," he says. "It changed everything—there is no way back. But the only way to support these brave people is to support them morally but not financially."

El-Sissi's popularity in Egypt is hard to judge. Polls indicate that the army is respected and that he is given credit for restoring order. But an accurate rating is difficult to ascertain: Most of the dissidents in the country have been silenced or driven abroad. Journalists are intimidated or imprisoned—most recently, a reporter named Hossam Bahgat was held for several days in November after reporting on the conviction of several members of the military.

"It's a mixed picture," says Kinninmont of el-Sissi's popularity rating. "It's not a ringing endorsement. People don't have a great deal of choice today—they see it as a choice between a military regime or an Islamic one."

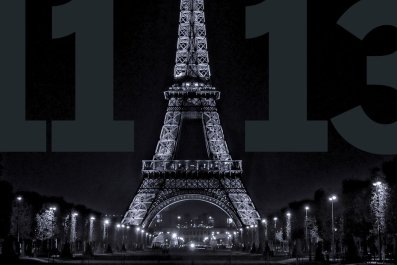

Now militants linked to ISIS are thought to have brought down the Russian passenger jet that crashed in the Sinai on October 31, killing 224 people. Egyptian security forces have already been battling ISIS militants in the Sinai Desert, and el-Sissi can be expected to ramp up operations against the group after this attack. If his past actions are any guide, he will take the opportunity to crack down even harder on his opponents, and the West will probably do little about it—particularly after the November 13 mass shootings and bombings in Paris that killed at least 129 people.

Says Hamid, "The sad lesson of the Arab Spring—or the crushing of the Arab Spring—is that brute strength works, violence works."