Archaeologists have found several ancient Mayan artifacts and fossils of long-extinct animals, including giant sloths, in the largest underwater cave system in the world—but warn that the mysteries of the caves' ancient history could be tarnished from nearby pollution.

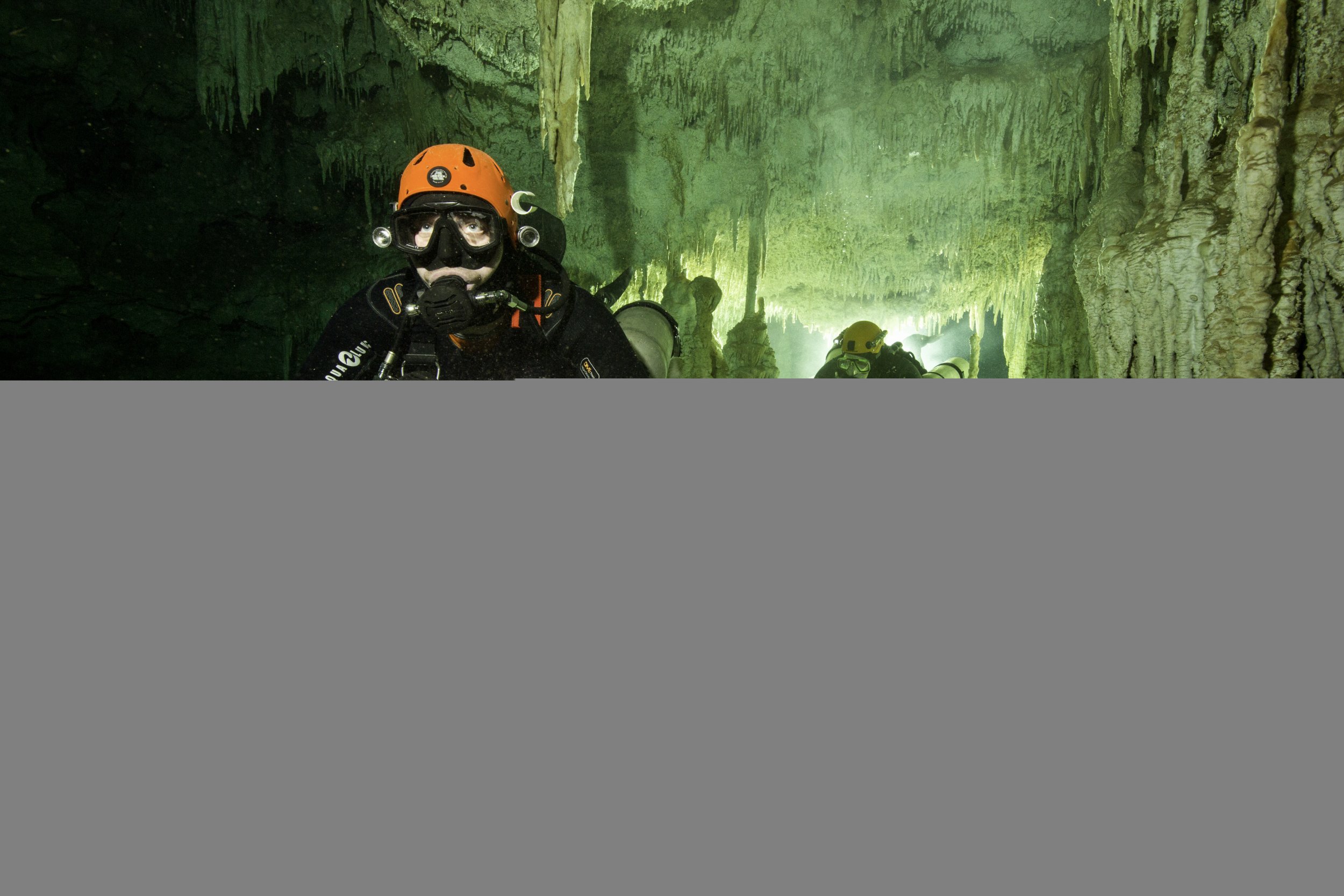

The 216-mile long flooded caves, known as the Sac Actun, were recognized as two distinct cave systems in Mexico. Last month, explorers of the Gran Acuífero Maya (GAM) announced that they discovered a passageway between the two, making it the largest cave system in the world.

On Monday, the archaeologists announced more details about what they found in the cave. Their discoveries include remains of an ancient elephant-like species called gomphotheres, giant sloths and bears, according to Agence France-Presse. They also found burned human bones, ceramics and wall etchings.

Upon the discovery of the caves last month, Robert Schmittner, the exploration director at GAM, said in a statement: "Now, everyone's job is to conserve it."

The caves' artifacts, however, are already at risk. Runoff from a nearby dump could be contributing to the high acidity levels in the cave where archaeologists found a human skull. The acid could damage the remains, reported the Associated Press. The cave systems are often linked to sinkhole-like structures known as cenotes, which are popular tourist destinations for swimming and snorkeling. Plus, the main highway that runs over the cave network has been known to collapse into further sinkholes, according to the AP.

Nearly 200 artifacts were found, most of which appear to be from the Mayan civilization, according to Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History. Some bones appear to be at least 9,000 years old. The explorers found a shrine to the Mayan god of commerce as well, with a staircase structure inside of the cenote.

The cenotes were known to be sacred to Mayan communities, in addition to providing people with freshwater. Per the AP, Guíllermo de Anda, underwater archaeologist and director of GAM, said that humans likely went down into the caves during droughts to look for water, though they probably did not live inside of them. The Mayan artifacts reveal that a drought likely caused the water levels to plummet around 1000 A.D., sending communities deeper inside to look for water.

"It is very unlikely that there is another site in the world with these characteristics," said de Anda, as reported by Agence France-Presse."There is an impressive amount of archaeological artifacts inside, and the level of preservation is also impressive."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Sydney Pereira is a science writer, focusing on the environment and climate. You can reach her at s.pereira@newsweekgroup.com.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.