When Newsweek published a story about David Bowie in October 1972, our pages said that "whatever world of rock is ultimately to succeed the Beatles, the Stones and the Who, it's having trouble being born. This is a time of confusion, a middle ages, an appropriate breeding ground for the dark, satanic majesty of England's David Bowie." At the time Bowie was still best known in the States through the persona Ziggy Stardust, as in his 1972 album The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars.

"I prefer being Ziggy to David. Who's David Bowie?" the star is quoted as saying in that article.

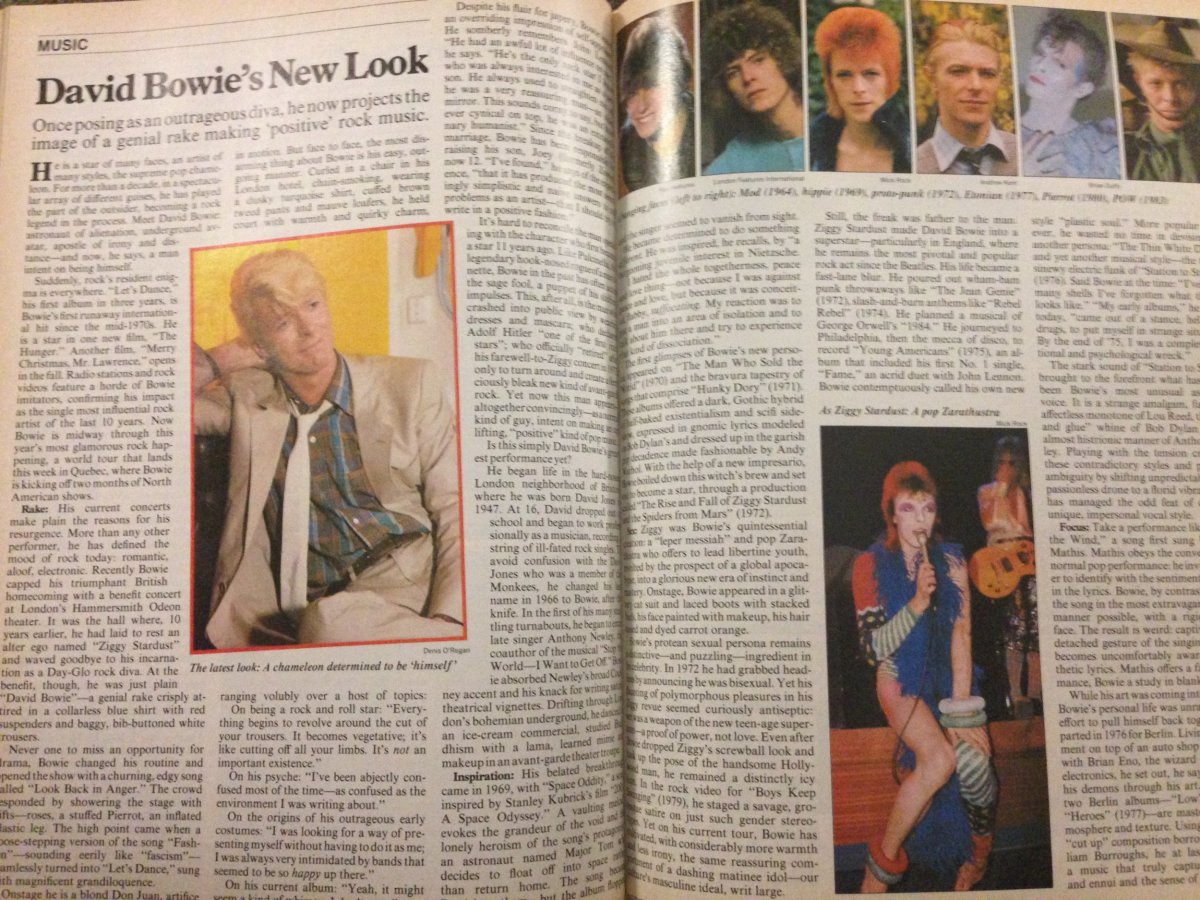

Just over a decade later, Newsweek ran a profile of Bowie, describing his "new look" and all those that had come in between. Writer Jim Miller called him "a star of many faces, an artist of many styles, the supreme pop chameleon" and "the single most influential rock artist of the last 10 years." The author grappled—presumably as Newsweek's readers did at the time—with the performer's many incarnations and seeming contradictions. How could he, and audiences, reconcile the mascara-wearing Ziggy of the previous decade with the guy being interviewed for the pages of a mainstream newsweekly in 1983?

It's now more than 30 years after that "new look" profile was published, and the world saw plenty more from Bowie in the ensuing decades.The star died Sunday, just two days after his 69th birthday and the release of his 28th album. As the world confronts the loss of Bowie, arguably one of the most prolific and influential musicians of the last half century, Newsweek looks back to its archives.

Read the full July 18, 1983 profile below.

David Bowie's New Look

Once posing as an outrageous diva, he now projects the image of a genial rake making 'positive' rock music.

By Jim Miller in London

He is a star of many faces, an artist of many styles, the supreme pop chameleon. For more than a decade, in a spectacular array of different guises, he has played the part of the outsider, becoming a rock legend in the process. Meet David Bowie; astronaut of alienation, underground avatar, apostle of irony and distance—and now, he says, a man intent on being himself.

Suddenly, rock's resident enigma is everywhere. Let's Dance, his first album in three years, is Bowie's first runaway international hit since the mid-1970s. He is a star in one new film, The Hunger. Another film, Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, opens in the fall. Radio stations and rock videos feature a horde of Bowie imitators, confirming his impact as the single most influential rock artist of the last 10 years. Now Bowie is midway through this year's most glamorous rock happening, a world tour that lands this week in Quebec, where Bowie is kicking off two months of North American shows.

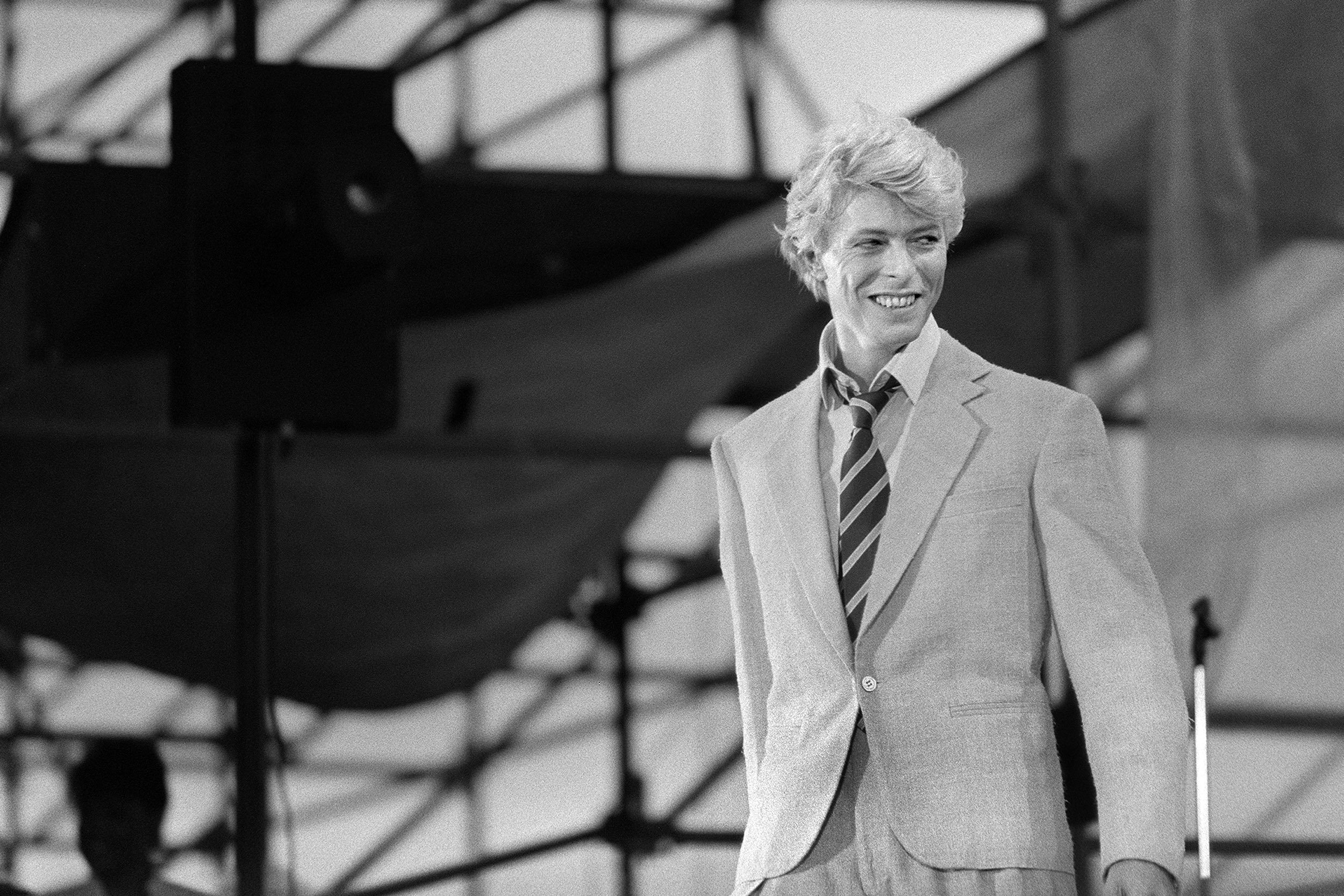

Rake: His current concerts make plain the reasons for his resurgence. More than any other performer, he has defined the mood of rock today: romantic, aloof, electronic. Recently Bowie capped his triumphant British homecoming with a benefit concert at London's Hammersmith Odeon theater. It was the hall where, 10 years earlier, he had laid to rest an alter ego named "Ziggy Stardust" and waved goodbye to his incarnation as a Day-Glo rock diva. At the benefit, though, he was just plain "David Bowie"—a genial rake crisply attired in a collarless blue shirt with red suspenders and baggy, bib-buttoned white trousers.

Never one to miss an opportunity for drama, Bowie changed his routine and opened the show with a churning, edgy song called "Look Back in Anger." The crowd responded by showering the stage with gifts—roses, a stuffed Pierrot, an inflated plastic leg. The high point came when a goose-stepping version of the song "Fashion"—sounding eerily like "fascism"—seamlessly turned into "Let's Dance," sung with magnificent grandiloquence.

Onstage he is a blond Don Juan, artifice in motion. But face to face, the most disarming thing about Bowie is his easy, outgoing manner. Curled in a chair in his London hotel, chain-smoking, wearing a dusky turquoise shirt, cuffed brown tweed pants and mauve loafers, he held court with warmth and quirky charm, ranging volubly over a host of topics:

On being a rock and roll star: "Everything begins to revolve around the cut of your trousers. It becomes vegetative; it's like cutting off all your limbs. It's not an important existence."

On his psyche: "I've been abjectly confused most of the time—as confused as the environment I was writing about."

On the origins of his outrageous early costumes: "I was looking for a way of presenting myself without having to do it as me; I was always very intimidated by bands that seemed to be so happy up there."

On his current album: "Yeah, it might seem a kind of whimsy. I don't care."

Despite his flair for japery, Bowie leaves an overriding impression of self-appraisal. He somberly remembers John Lennon. "He had an awful lot of influence on me," he says. "He's the only rock star I know who was always interested in me as a person. He always used to straighten me up; he was a very reassuring man—an older mirror. This sounds corny to say, but however cynical on top, he was an extraordinary humanist." Since the breakup of his marriage, Bowie has been responsible for raising his son, Joey (formerly Zowie), now 12. "I've found," he says of the experience, "that it has produced the most seemingly simplistic and naive answers to my problems as an artist—that I should try to write in a positive fashion."

It's hard to reconcile the man speaking with the character who first became a star 11 years ago. Like Pulcinella, the legendary hook-nosed rogue of a marionette, Bowie in the past has often acted the sage fool, a puppet of his shifting impulses. This, after all, is the man who crashed into public view by wearing dresses and mascara; who declared Adolf Hitler "one of the first rock stars"; who officially "retired" after his farewell-to-Ziggy concert in 1973, only to turn around and create a ferociously bleak new kind of avant-garde rock. Yet now this man appears—altogether convincingly—as a normal kind of guy, intent on making an uplifting, "positive" kind of pop music.

Is this simply David Bowie's greatest performance yet?

He began life in the hard-nosed London neighborhood of Brixton, where he was born David Jones in 1947. At 16, David dropped out of school and began to work professionally as a musician, recording a string of ill-fated rock singles. To avoid confusion with the Davy Jones who was a member of the Monkees, he changed his last name in 1966 to Bowie, after the knife. In the first of his many startling turnabouts, he began to emulate singer Anthony Newley, the co-author of the musical Stop the World—I Want to Get Off. Bowie absorbed Newley's broad Cockney accent and his knack for writing satiric theatrical vignettes. Drifting through London's bohemian underground, he danced in an ice-cream commercial, studied Buddhism with a lama, learned mime and makeup in an avant-garde theater troupe.

Inspiration: His belated breakthrough came in 1969, with "Space Oddity," a song inspired by Stanley Kubrick's film 2001: A Space Odyssey. A vaulting melody evokes the grandeur of the void and the lonely heroism of the song's protagonist, an astronaut named Major Tom who decides to float off into space rather than return home. The song became Bowie's anthem—but the album flopped, and the singer seemed to vanish from sight.

He became determined to do something different. He was inspired, he recalls, by "a burgeoning juvenile interest in Nietzsche…I hated the whole togetherness, peace and love thing—not because I was against peace and love, but because it was conceited, flabby, suffocating. My reaction was to put a man into an area of isolation and to talk about him there and try to experience that kind of dissociation."

The first glimpses of Bowie's new persona appeared on "The Man Who Sold the World" (1970) and the bravura tapestry of songs that comprise Hunky Dory (1971). These albums offered a dark, Gothic hybrid of half-baked existentialism and sci-fi sideshow, expressed in gnomic lyrics modeled on Bob Dylan's and dressed up in the garish pop decadence made fashionable by Andy Warhol. With the help of a new impresario, Bowie boiled down this witch's brew and set out to become a star, through a production called The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1972).

Sex: Ziggy was Bowie's quintessential creation: a "leper messiah" and pop Zarathustra who offers to lead libertine youth, revolted by the prospect of a global apocalypse, into a glorious new era of instinct and mastery. Onstage, Bowie appeared in a glittery cat suit and laced boots with stacked heels, his face painted with makeup, his hair teased and dyed carrot orange.

Bowie's protean sexual persona remains a distinctive—and puzzling—ingredient in his celebrity. In 1972 he had grabbed headlines by announcing he was bisexual. Yet his flaunting of polymorphous pleasures in his Ziggy revue seemed curiously antiseptic: sex was a weapon of the new teen-age superman—a proof of power, not love. Even after Bowie dropped Ziggy's screwball look and took up the pose of the handsome Hollywood man, he remained a distinctly icy icon. In the rock video for "Boys Keep Swinging" (1979), he staged a savage, grotesque satire on just such gender stereotypes. Yet on his current tour, Bowie has cultivated, with considerably more warmth and less irony, the same reassuring comportment of a dashing matinee idol—our culture's masculine ideal, writ large.

Still, the freak was father to the man. Ziggy Stardust made David Bowie into a superstar—particularly in England, where he remains the most pivotal and popular rock act since the Beatles. His life became a fast-lane blur. He poured out wham-bam punk throwaways like "The Jean Genie" (1972), slash-and-burn anthems like "Rebel Rebel" (1974). He planned a musical of George Orwell's 1984. He journeyed to Philadelphia, then the mecca of disco, to record Young Americans (1975), an album that included his first No. 1 single, "Fame," an acrid duet with John Lennon. Bowie contemptuously called his own new style "plastic soul." More popular than ever, he wasted no time in devising yet another persona: "The Thin White Duke," and yet another musical style—the tough, sinewy electric funk of Station to Station (1976). Said Bowie at the time: "I've got so many shells I've forgotten what the pea looks like." "My early albums," he recalls today, "came out of a stance, helped by drugs, to put myself in strange situations. By the end of '75, I was a complete emotional and psychological wreck."

The stark sound of Station to Station brought to the forefront what has always been Bowie's most unusual asset—his voice. It is a strange amalgam, fusing the affectless monotone of Lou Reed, the "sand and glue" whine of Bob Dylan and the almost histrionic manner of Anthony Newley. Playing with the tension created by these contradictory styles and producing ambiguity by shifting unpredictably from a passionless drone to a florid vibrato, Bowie has managed the odd feat of creating a unique, impersonal vocal style.

Focus: Take a performance like "Wild Is the Wind," a song first sung by Johnny Mathis. Mathis obeys the conventions of a normal pop performance: he invites a listener to identify with the sentiments expressed in the lyrics. Bowie, by contrast, interprets the song in the most extravagantly affected manner possible, with a rigidly straight face. The result is weird: captivated by the detached gesture of the singing, a listener becomes uncomfortably aware of the bathetic lyrics. Mathis offers a fantasy of romance, Bowie a study in blankness.

While his art was coming into fresh focus, Bowie's personal life was unraveling. In an effort to pull himself back together, he departed in 1976 for Berlin. Living in an apartment on top of an auto shop and working with Brian Eno, the wizard of "ambient" electronics, he set out, he says, to exorcize his demons through his art. Bowie's first two Berlin albums—Low (1977) and Heroes (1977)—are masterpieces of atmosphere and texture. Using techniques of "cut up" composition borrowed from William Burroughs, he at last was making a music that truly captured the angst and ennui and the sense of claustrophobia that had always run through his lyrics.

In the years since, Bowie has made a concerted effort to escape from what he calls the "blinkered" life-style of most rock stars. He lives off the beaten path in Switzerland and paints for his own pleasure. His film career began in earnest with The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976), Nicolas Roeg's ambitious pageant of extraterrestrial alienation. Since then, with varying success but an instinct for taking risks, he has played a Prussian stuffed tuxedo in Just a Gigolo (1978), a rapidly aging vampire in The Hunger (1983) and a tough-willed POW imprisoned by the Japanese on Java in the upcoming Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence. On Broadway, he won praise for his performance as John Merrick in The Elephant Man (1980).

But Bowie's bread and butter remains rock and roll. Three years ago, in "Ashes to Ashes," Bowie exhumed the character of Major Tom in a song that implied that "Space Oddity" was really a metaphor for psychotic withdrawal. The record neatly tied up Bowie's career and left him free to pick and choose from 14 years of different musical styles. On Let's Dance, his current album, he's opted for "plastic soul," take two. With its upbeat lyrics, riffing saxophones and piquant reminders of darkness and dissonance, it is a shrewd retreat from the brave new music Bowie forged in Berlin.

Cracks in the Mask: The "real" David Bowie meanwhile remains as elusive as ever—particularly for a critic trying to appraise a career filled with such abrupt twists and turns. At the end of "Young Americans," Bowie sings, in a memorably plangent tone, "Ain't there one damn song that can make me break down and cry?" The question seems pertinent after listening to all of Bowie's work. He has crafted a dizzying array of personas; he has pioneered an effectively harsh style of hammering, metallic new music, and he has taken the theatrical mechanics of rock and roll and exposed their inner workings to anyone who cares to look. A cynic might note the glibness of Bowie's style, the recurrence of commercial ploys, the unattractive coldness of much of his music. A sociologist might explore the mirror Bowie holds up to our culture and echo critic Tom Carson's remark: "In an age of artifice, he was the master artificer."

But after hours of listening to Bowie, what sticks are the many odd little cracks in his masks, where the pang in his voice makes isolated phrases bob to the surface like flotsam from a shipwreck: "Can you hear me, Major Tom?" "We can be heroes, just for one day." "I've never done anything out of the blue." He may not make you cry. But with the formal restraint, restlessness and self-consciousness of a true modernist, Bowie at these moments has reinvented rock and roll as an expressive medium. He is our Pulcinella of the id.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.