On June 15, 2015, Brendan Klinkenberg ate a burrito. It was a breakfast burrito packed with eggs, bacon, avocado, beans and cheese. Several hours later, he ate another burrito for lunch. Then, for dinner, a carnitas burrito, which he purchased at a taqueria in the Mission neighborhood of San Francisco. Klinkenberg repeated the diet—skipping breakfast—the following day. And the next day, and the day after that.

After a hellish week of this, Klinkenberg published a BuzzFeed post: "I Ate Nothing But Burritos for a Week."

"It was a mistake," Klinkenberg, then a tech reporter at BuzzFeed, says a year after his burrito cleanse. "You shouldn't eat only burritos for a week. It feels terrible." The idea was pitched to him by an editor, though Klinkenberg happily consented. The headline was guaranteed to garner attention. BuzzFeed would pay for the burritos. That's a week of free meals. Why not?

"I thought it was kind of a silly idea and I'd just do it and be done with it," Klinkenberg adds. "But it was pretty bad. You just feel like garbage." In his write-up, he declared it "the dumbest thing I've ever done" and "not worth the tortilla-wrapped misery."

Other journalists have done far worse.

"I've smoked coffee grounds, ate gourmet dog food, got drunk off a humidifier full of vodka and most recently tried to get drunk off a few gallons of Kombucha," says Jules Suzdaltsev, a writer who has taken stunt journalism to its logical extremes.

A decade ago, stunts like this might have been fodder for a reality show, like Fear Factor or maybe Jackass. Today, the Jackasses are just as likely to be professional journalists, dressing up as Marilyn Monroe or strapping on an adult diaper in the name of content. And as ad models shift toward video and live streams, journalists are now eating paper and freezing themselves in cryotherapy chambers on camera.

When did journalism become so... physically degrading?

Immersive journalism is not new. In 1887, the reporter Nellie Bly feigned insanity in order to be committed to a New York City insane asylum. Her stay resulted in a landmark undercover account of appalling conditions at the Women's Lunatic Asylum. Eighty-odd years later, Hunter S. Thompson wrote a manic first-person account of the 1970 Kentucky Derby, which more or less invented the genre now known as Gonzo journalism.

"What's happened now," says Duy Linh Tu, a professor at the Columbia School of Journalism, "is there's been an escalation in the types of stuff [writers will] do." Stunt journalism is pretty easy to define: It's any article wherein a writer becomes a guinea pig, attempting some masochistic or outrageous challenge in an attempt to prove a point or provide a first-hand experiential account. But it's not so easy to trace its history; nobody can really tell you when stunt journalism evolved into today's more sensationalist form, so let's just go with May 2007. That was the month Vice magazine had an intern masturbate into an ice tray for a week, freeze the semen and then eat 12 multi-flavored "cumsicles" (ew) formed from his seed.

There are basically four big categories of stunt journalism—sex, food, body horror and fashion/beauty. The Vice intern's dirty deed done dirt cheap ticks off at least three of those boxes. Nine years later, the stomach-churning story has been largely scrubbed from the internet, but the try-anything ethos has blossomed into a cottage industry. Women's magazines have cornered the market on sex stunts: One brave Cosmopolitan contributor who writes under the apparent pseudonym Krista McHarden has tried cannabis lube, given her boyfriend a "grapefruit blow job," eaten a doughnut off of the boyfriend's penis and tried boning with a female condom.

"[There are] a lot of young journalists who are doing these things for very, very little pay," says Lauren Larson, an editorial assistant at GQ who in February mocked the phenomenon with a satirical list of Free Stunt-Journalism Ideas for Aspiring Writers. "Sometimes it's really funny and sometimes it's really, really stupid."

Larson's piece envisions a future overrun by "a bunch of J-school grads in adult diapers, eating burritos." It's not so far off. Then there is the live-like-a-celebrity genre: One writer lived like Khloé Kardashian for a week; another lived like Marilyn Monroe. The Cut published "My Week Living Like Shailene Woodley," HelloGiggles ran "I Lived Like Chrissy Teigen for Five Full Days," The Tab posted "I Lived Like Donald Trump For a Week" (how?) and Elle published a serialized, four-part post titled "I Lived Like Kim Kardashian for a Week." "You can interview people or do a bunch of research on a particular topic," says Brooke Shunatona, an editor with Cosmopolitan who lived like Kylie Jenner for a week, "but you don't actually really know or understand until you've done it yourself."

The stunt piece headline is nearly always a first-person, declarative statement. The first word is "I" or "We" or maybe "What Happened When I..." You have seen them float across your social feeds, screaming for a click: I Let My Boyfriend Dress Me for a Week. I Fertilized My Salad with Period Blood. I Tried Anal Weed Lube So You Don't Have To. I Put Scrunchies on my Boyfriend's Penis. I Dressed Like Hermione Granger For a Week & This Is What Happened. I Came to Work Wearing Only Underwear (and This Is What Happened). I Wore a Spandex Diaper to a Strip Club So I Could Come While Receiving a Lap Dance.I Tried to Eat Hot Dogs Competitively and Nearly Died. I Lived as Marilyn Monroe for a Week. I Used Men's Beauty Products for a Week. I Took a Photograph of Everything I Ate for a Month. I Tried Living Like Dan Bilzerian and Realized What His Problem Is. I Put Edible Body Paint on my Boobs and Rubbed Them All Over my Boyfriend. I Read and Replied to Every PR Email I Received for a Week.

I wrote the last one, by the way. I'm not above this.

The stunt piece might be understood as a distant cousin of the personal essay, the confessional form that now commands great power and even greater traffic on sites like Thought Catalog and xoJane. It's similarly intimate, except the pain—physical or otherwise—is self-inflicted. It flows out of a capitalist self-interrogation that's familiar to Leonardo DiCaprio: "How much bodily and emotional harm am I willing to do to myself for the sake of my career?"

And while no journalist has (yet) tried imitating DiCaprio's grueling regimen in The Revenant—sleeping in animal carcasses, eating raw bison liver, risking hypothermia—movies are a popular source of stunt ideas. In 2015, the Jezebel staff valiantly tried masturbating to the Fifty Shades of Grey soundtrack. The same month, that Cosmopolitan contributor attempted to complete every sex act from the film with her boyfriend in a single weekend. The write-up was more exhausting than erotic (sample line: "His hips are thrusting but there's no light behind his eyes"). More recently, a Refinery29 writer published a piece titled "What Happened When I Ate Like a Disney Princess for a Week," taking dietary cues from animated Disney icons like Belle and Ariel.

Each of these pieces contains incidental traces of the personal essay, whether it's the Disney dieter revealing her childhood Little Mermaid obsession or the Fifty Shades sex-marathoner confessing that she maintains a Sexual To-Do list in a Google Doc somewhere. But the tone is different. The personal essay searches inward, mining personal experiences for content; stunt journalism searches outward, creating experiences from scratch. It's a neat trick: You're no longer required to have an interesting life in order to write about yourself. The personal essay declares: Here's a Private, Harrowing Thing That Happened To Me. The stunt piece cries out, from a state of deep depravity: Check Out This Fucked Up Thing I Did to Myself. The stunt piece emerges from a place of intrepid journalistic daring or just old-fashioned poor judgment (they are not always distinguishable from one another). It's a tale of endurance rather than survival.

"I think it's kind of like the [man's] answer to the personal essay," says Larson, the GQ satirist. "They get to personalize it and use a lot of the first-person, but it's still couched in this goofy idea. With men, it's like, 'I only drank alcohol for 96 hours.' I think Vice did that." ("It didn't kill me," raved the writer who carried out that stunt, but he did struggle to differentiate blood from Bloody Mary mix in his bowel movements.)

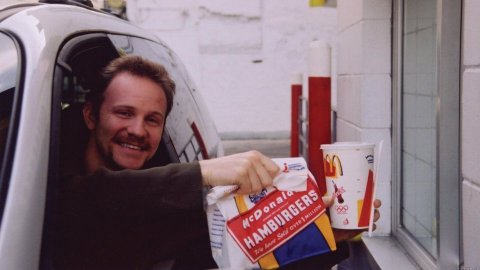

If the modern stunt essay has a film antecedent, it's Super Size Me, Morgan Spurlock's 2004 hit documentary chronicling his own attempt to gorge on nothing but McDonald's food for 30 days. However jokey it seemed, the stunt served the public interest in clear ways: Spurlock drew national attention to the obesity epidemic, and McDonald's discontinued its Super Size option shortly after the film premiered. Less journalistic value is accomplished by ingesting nothing but alcohol for a week. Duy Linh Tu, the journalism professor, wonders whether the term "stunt journalism" is a misnomer. "I don't think all of this is journalism," Tu says. "I'm not making a quality judgment. It's all content.... [But] you won't be able to build a long-term journalistic organization pulling these stunts."

You might envision stunt journalism as a giant spectrum, with "newsworthy" on one end and "existentially pointless" on the other. In the former category, you'll find Mother Jones's powerful recent dive into life as a prison guard or Motherboard's Soylent investigation, "How I Ate No Food For 30 Days." In the latter—well, if you can read the entirety of Vice's account of feeding laxatives to strangers wearing adult diapers, that's a stunt in and of itself.

There are other categories, too, like the stunt piece where you can't tell if it's a parody or not ("I'm 23 and Dressed as Royal Baby Prince George For a Week") and the stunt piece that's so mundane it barely qualifies as a stunt ("I Tried Waking Up an Hour Earlier Every Day for a Week") and the stunt piece that doesn't follow through on its headline ("I Paid This Company $30 to Break Up with My Girlfriend") and the stunt piece that's been done way too many times before (see: "I Let My Boyfriend Dress Me for a Week" boyfriends, as ranked by Gawker). Bad writing can sink a good premise, but good writing can also lift a ho-hum stunt: "I Stopped Giving My Husband Blow Jobs for a Month," by Cosmopolitan's mystery writer, turns out to be a very funny rumination on sexual routines and sacrifices in a relationship. It all depends on the writer. "I'll read David Foster Wallace drinking bone broth for a week," says Larson, "but it's just not as interesting when it's a young person starting out and trying these increasingly crazy stunts."

At Columbia, Tu isn't teaching his journalism students how to dress like Disney princesses. "We don't talk about it," he says. "Not because we don't think it's something our students would ever be exposed to or lean towards. We just have other fish to fry." That said, his students "might go to a place like Vice or BuzzFeed or any of these online platforms that get very loosy-goosy with what's allowable," Tu adds. "Maybe we should address it more."

Super Size Me, though, proved prophetic in subject as well as style: Stunt journalism frequently involves fast food and extreme diets. A few months after the burrito piece, Cosmopolitan published "I Only Ate Pizza for a Week and I Lost 5 Pounds." Another reporter tried eating nothing but Chick-fil-A for a full 30 days, while a BuzzFeed contributor tasted 12 different brands of cat food. Sometimes the fast food industry's concoctions are so ghastly that merely sampling the latest item on the menu passes for a stunt. In 2015, for instance, Time, Fox News, The Washington Post, USA Today, Time Out and Newsweek all made a big show of tasting Pizza Hut's "hot dog-crusted pizza" monstrosity. (One wonders if the foods themselves are created to solicit exactly this kind of coverage for free advertising. It's not so far-fetched, considering Chilis made an Instagram-friendly burger bun.) More memorably, ex-Gawker writer Caity Weaver famously gorged herself on unlimited mozzarella sticks as part of a nightmarish TGI Friday's deal. And in other cases, the food is pretty much incidental: Dan Ozzi, an editor at Noisey, recently spent 12 hours in Taco Bell on 4/20—the ultimate weed holiday. (Full disclosure: I've contributed to Noisey and have worked with Ozzi.) He describes the stunt as "really isolating and boring."

"There's a thirst for content," says Ozzi. "There's a need for all-purpose, evergreen content all the time. This one in particular—I realize that I'm insulting myself by saying this, but it also says a lot about journalism that it's a very me-focused thing: 'Oh, I did this. I went out and did this stupid thing.' It is very focused on the writer, because digital media makes it so that online popularity is the new form of currency."

Especially now that content creators are stunting not just behind the laptop but in front of the camera, too. BuzzFeed Video is owed some credit—or blame—for the shift. BuzzFeed's "Try Guys" (a team of guys who, well… "try" things) have racked up millions of views exploring zany, gender-bending antics on camera: trying cosplay, trying on wedding dresses, simulating the feel of going into labor, changing a diaper for the first time. More than shock value, these videos make a desperate bid for relatability, the secret ingredient for converting mundane subject matter into viral manna. Look! they scream. These men are discovering how gross it is to change a diaper!

Many of the stunts amount to a kind of superficial tourism of gender, class, or race. BuzzFeed's diary of a flannel-wearing dude wearing makeup for a week (which has well over a million views), for example, attempts something that women do daily just long enough to produce viral content but not seriously enough to produce much insight. Writing for Gawker, Leah Finnegan likened the piece to John Howard Griffin's book Black Like Me, deriding it as "stuntertainment at its worst: doing something a large swath of the population does every day as if it's a remarkable act."

In recent months, the advent of Facebook Live—the social network's bid to become not just an unending stream of updates on your ex but also a 24-hour TV channel where you can watch your ex snore in real time—has both bolstered and redefined stunt journalism. The livestream form encourages stunts that are visually alluring and immediately gratifying (hardly anyone is going to tune in to your stream for more than, say, 10 minutes at a time). So when BuzzFeed got nearly a million viewers to watch two guys in smocks explode a watermelon on Facebook Live, the landmark antic spawned dozens of "future of media" blog posts and nearly as many copycat stunts. A week later, Mic, a prominent BuzzFeed competitor, broadcast its staffers donning lab coats and blowing things up in real time, to significantly less fanfare.

Meanwhile, a Washington Post columnist literally ate his words on camera, swallowing down a "newspaper ceviche" with graceful composure, while the New York Post had its staffers attempt to eat three pounds of artisanal cheese on Live. As a May headline on Recode phrased it: "Facebook Live is turning journalists into bad Jackass copycats."

This is an old journalistic instinct—don't look for a story, be the story—funneled through new media channels. It's not the recklessness that's new (war reporters have long put themselves at risk) but the desperation. Still, what the stunt piece and the personal essay have in common is that the best writing stems from horrible experiences—and that neither of them are going away soon. The stunt craze is liable to change how would-be journalists go about breaking into the industry. Or maybe it already has.

"Whenever kids ask me how to get into writing, I'm always just like, 'You know how to get into writing? Go fuck up your life really bad,'" Ozzi says. "Go do something really stupid. And then write about it. That's where good stories come from."