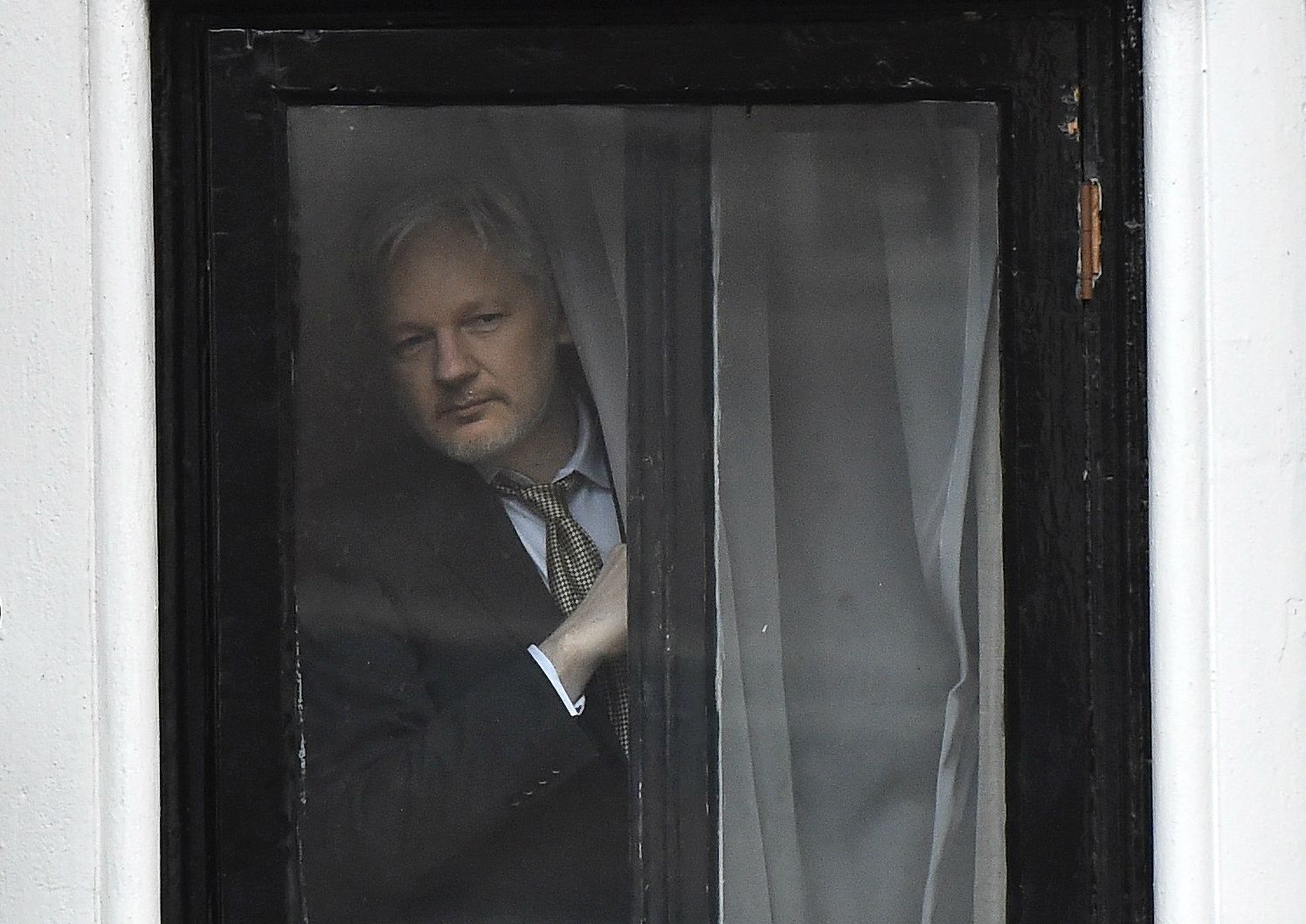

On a drizzly Friday morning in February, on a pavement outside London's Ecuadorian embassy, police and press gathered to await the emergence of the world's most famous, and divisive, whistleblower—Julian Assange. Many of those in the press pack, numbering around a hundred journalists from around the world, had been there since the day before. The half dozen police assembled had been waiting, on and off, for almost four years.

The previous day, Assange, who founded the controversial WikiLeaks organisation that publishes confidential documents and images, had said he would walk out of the embassy and into police handcuffs if a U.N. panel failed to rule his detention unlawful. If the panel found in his favour, he said he expected the immediate return of his passport and to be allowed safe passage out of Britain. That morning at 10am the ruling officially went his way, and cameras poking out from umbrellas pointed towards the front door. But he did not emerge.

Despite the U.N's decision, the U.K. did not comply and Assange's passport was not returned. For the 1,326th day in a row, he remained cooped up in his gilded cage.

The unusual case of Julian Assange has been referred to contrarily as "one of the epic miscarriages of justice in our time," by the journalist John Pilger and an evasion of justice by the U.K.'s Foreign Secretary Philip Hammond. He has been lauded as a "champion of free speech" by Amnesty International and condemned as a "high-tech terrorist" by the U.S. Vice-President Joe Biden. The U.N. ruling served to only further divide opinion.

What the U.N working group on arbitary detention had concluded from its 16-month investigation was that Assange's stay at the embassy was in direct contravention of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. It called for the governments of the U.K. and Sweden to allow Assange his right to freedom of movement and grant compensation for his time spent at the embassy. Assange sought asylum there in 2012 to avoid extradition to Sweden where he is wanted for questioning over a rape allegation which he denies. The Australian national and his supporters claim the accusation is part of a wider conspiracy to force his extradition to the U.S. in order to face charges over leaking secret government documents.

Unfortunately for Assange, and what the Swedish prosecution was quick to point out, the U.N.'s ruling is not legally binding in a U.K. court of law. Hammond immediately branded the idea that he was being unlawfully detained as "ridiculous", while Prime Minister David Cameron said: "The only person who detained himself was himself."

Cameron's claims, Assange says, are about saving face. "The U.K. Prime Minister is making false statements in parliament, he's attacking me," Assange tells Newsweek during a recent phone interview from the embassy. He defiantly refers to the comments as being part of a "media war" but adds, "despite Sweden, the U.K. and the U.S. being very well resourced states—diplomatically and in the intelligence sector—they lost in litigation against a single person. It's really a historic victory."

Victory or not, no one has budged. If anything, the U.S.-Sweden-U.K.-Assange deadlock has tangled itself a little tighter in the wake of the ruling. His lawyer, Melinda Taylor, argues that Britain and Sweden are undermining the moral authority of the U.N. and becoming "rogue nations" guilty of defying human rights rulings.

"You can't just support the United Nations when it says what you want it to say," Taylor tells Newsweek. "Laws have to be universal and they have to be applied universally. If the U.K. and Sweden are serious about the U.N. being impartial and effective, they can't allow these double standards to be propagated."

One possible route through the deadlock is for the Swedish prosecutors to come to London to interview Assange at the embassy. Prosecutor Marianne Ny's lack of response to an open invitation from both Ecuador and Assange's lawyers has been criticised by senior figures in Sweden's legal community, with the head of the Swedish Bar Association calling the impasse a "circus."

Last year, documents uncovered by Italian news magazine l'Espresso revealed that a lawyer with the U.K.'s Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) had advised Ny in an email that "it would not be prudent for the Swedish authorities to try to interview the defendant in the U.K.," claiming that he would be under no obligation to answer questions. Assange's legal team believe this is proof the prosecutors are "more interested in winning the case than finding the truth."

#Assange detention: What Sweden knew and when it knew it: #svpol More: https://t.co/LJVOVHHvmt pic.twitter.com/uAJ2fQVZBJ

— WikiLeaks (@wikileaks) August 10, 2015

Elisabeth Massi Fritz, the lawyer representing one of the alleged victims, said in 2014 that her client would be willing to wait until the statute of limitations on the case—the time period legally allowed for charges to be made—expires to get justice. Following the most recent developments, Fritz refused to say whether the ruling would prompt prosecutors to travel to London, instead telling Newsweek she encourages Assange to "pack his bags, step outside the embassy and begin to cooperate."

Holing himself up inside the embassy for another four years until the statute of limitations expires would appear to offer a plausible end to the stalemate. Last August, Swedish prosecutors were forced to drop their investigation into three of the allegations—two of sexual molestation and one of unlawful coercion—as they ran out of time to question him. However, before the time expires on the final allegation in 2020 there is the possibility that the U.S. will file its own extradition warrant, putting Assange back to square one. Former U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder has previously said officials were pursuing a "very serious criminal investigation" into Assange and WikiLeaks.

The Ecuadorian government has reportedly come up with elaborate ways of their own to get Assange out of their embassy. A document seen by Buzzfeed and Ecuadorian news site Focus Ecuador revealed one option considered was to appoint Assange as Ecuador's U.N. representative, gaining him diplomatic immunity and allowing him safe passage to Ecuador where he has been granted asylum.

Another option was to smuggle him out in a diplomatic bag, while the most audacious plan involved a "discreet exit". "Assange could leave in fancy dress," the document suggests. "Or try to escape across the rooftops towards a nearby helipad, or get lost among the people in Harrods." There is no evidence to suggest that any of the escape plans were ever attempted, but Twitter users still had some fun with the concept.

@asabenn @maitlis @GeneralBoles 'I have no idea who Julian is, my name's Colin and I'm just off to a party' pic.twitter.com/Q4tyI6zEI8

— Elliot Wagland (@elliotwagland) September 1, 2015

There's also the question of the impact continued confinement will have on Assange's health. In September, after Assange complained of acute pain in his right shoulder, the U.K. Foreign Office refused a request filed by the Ecuadorian embassy for him to visit a hospital without being arrested.

"I have a health problem which means that I am in serious pain," Assange says. "I have pain killers for that but my doctors say that I need to have an MRI, which is not possible to do in the embassy."

Medical experts also warn Assange's lack of access to fresh air and sunlight could put him at risk of certain cancers, heart disease and bone conditions like osteoporosis, as well as taking a toll on his mental health. Psychologist Dr. Lesley Perman-Kerr says prolonged confinement in the embassy leaves Assange prone to depression, anxiety and nightmares. "There may also be a huge sense of what has been lost in terms of everyday integration with family and friends," she says. "Psychologically this can manifest itself as depression."

The worst case scenario, for Assange and his supporters, if he does step outside the embassy door would be arrest and extradition to Sweden, followed by extradition to the U.S. where he faces indefinite incarceration and, he believes, torture. His team point to the case of Chelsea Manning, who was convicted in 2013 for violations of the U.S.'s Espionage Act after providing classified documents to WikiLeaks. Manning was subjected to "cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment," according to the U.N.'s special rapporteur on torture, after being forced to spend almost a year in solitary confinement prior to her conviction. Assange would not willingly expose himself to such treatment, says Gavin MacFadyen, director of the Centre for Investigative Journalism in London and a personal friend of the Wikileaks founder. "He would not submit to a decades-long sentence in a U.S. maximum security prison," MacFadyen tells Newsweek. "Murder, gang rape, intimidation and violence are almost the norm [there]."

Could Assange last another four years in the embassy? Or will poor health force him out? "At a certain point he'll have to weigh up whether the risk of torture in the United States is worse than the constant mental torture he's suffering now," Taylor says. "And I worry that balance has already been reached." With no definitive end to the deadlock in sight, Assange—and the legion of powerful adversaries he has amassed—isn't going anywhere.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Anthony Cuthbertson is a staff writer at Newsweek, based in London.

Anthony's awards include Digital Writer of the Year (Online ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.