A highly unusual album was among Monday night's Grammy nominees in the world music category: Zomba Prison Project, recorded by 14 men and women incarcerated in a filthy, dilapidated maximum-security prison in the impoverished nation of Malawi, and two of their guards. They sang about the life lessons learned and meted out by murderers, robbers and rapists, and went up against far better-known performers in the world music category.

The Zomba prison band didn't win the Grammy, but the mere fact that their voices caught the attention of the global entertainment industry was music to the ears of author Baz Dreisinger, who spent two and a half years visiting nine of the world's prisons, including some of its bleakest, and has just published a book called Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World (Other Press, February 2016).

In New York, Dreisinger runs the Prison-to-College Pipeline program at John Jay College. She has led restorative justice workshops in prisons in South Africa and Rwanda, started a creative writing workshop in a Uganda prison and co-led a drama workshop at a Thailand prison. She talked to Newsweek about her world prisons tour and what she found.

Monday night, Malawi's Zomba prison band was nominated for a Grammy. There's a rich history of prison music. Where does it come from?

From slave spirituals to chain gang work songs, right up to the music of artists like Lead Belly and the prison blues of Johnny Cash, music and prison have a long history of being intertwined in this country, in part because oppression demands an emotional release and music is the ultimate release. I've heard of music being used as a form of healing or therapy in countries ranging from Norway and Jamaica to Israel and India.

There's an acknowledgment that music not only promotes self-awareness and reduces anxiety but also is conducive to peer bonding and cohesive group dynamics. Certainly, art and music possess tremendous healing power and transformative capabilities, especially in a prison context. Studies have shown this, and I witnessed it. I visited a prison music program in Jamaica, where a makeshift reggae studio was a tiny bastion of sanity in what was otherwise a hellhole. Incidentally, one of the products of that music program—the Jamaican artist Jah Cure, who has been out of prison and making beautiful music for nine years now—was nominated for a Grammy last night too.

How did you select the prisons you visited?

I selected these countries because they were in some way representative of a particular issue I wanted to take on, whether philosophical questions around forgiveness and reconciliation (Rwanda and South Africa); questions about the role of the arts in prisons (Uganda and Jamaica); the crisis facing incarcerated women (Thailand); the ills of solitary confinement (Brazil); the vexed dynamics of private prisons (Australia); the dilemma of prisoner re-entry (Singapore); or, finally, larger visions of what justice might look like (Norway). I was especially interested in finding pockets of progressive thinking in what seem to be unexpected places, like Singapore and Uganda.

You did not include American prisons. Why?

As the founding academic director of the Prison-to-College Pipeline program at John Jay College, where I teach, I spend a lot of time in American prisons, teaching and working with people coming back to the community. So American prisons are very present in the book, as the backdrop against which all of my observations and ideas are set. I constantly use my work in U.S. prisons as my reference point, and this makes sense considering the American prison model is so globally influential and so massive: We hold 25 percent of the world's prisoners, with only 5 percent of the world's population. In many respects, the American model is the one that has been foisted upon the world, so we can "see" America in all of the world's prisons.

Which of the prisons you visited was the worst and why?

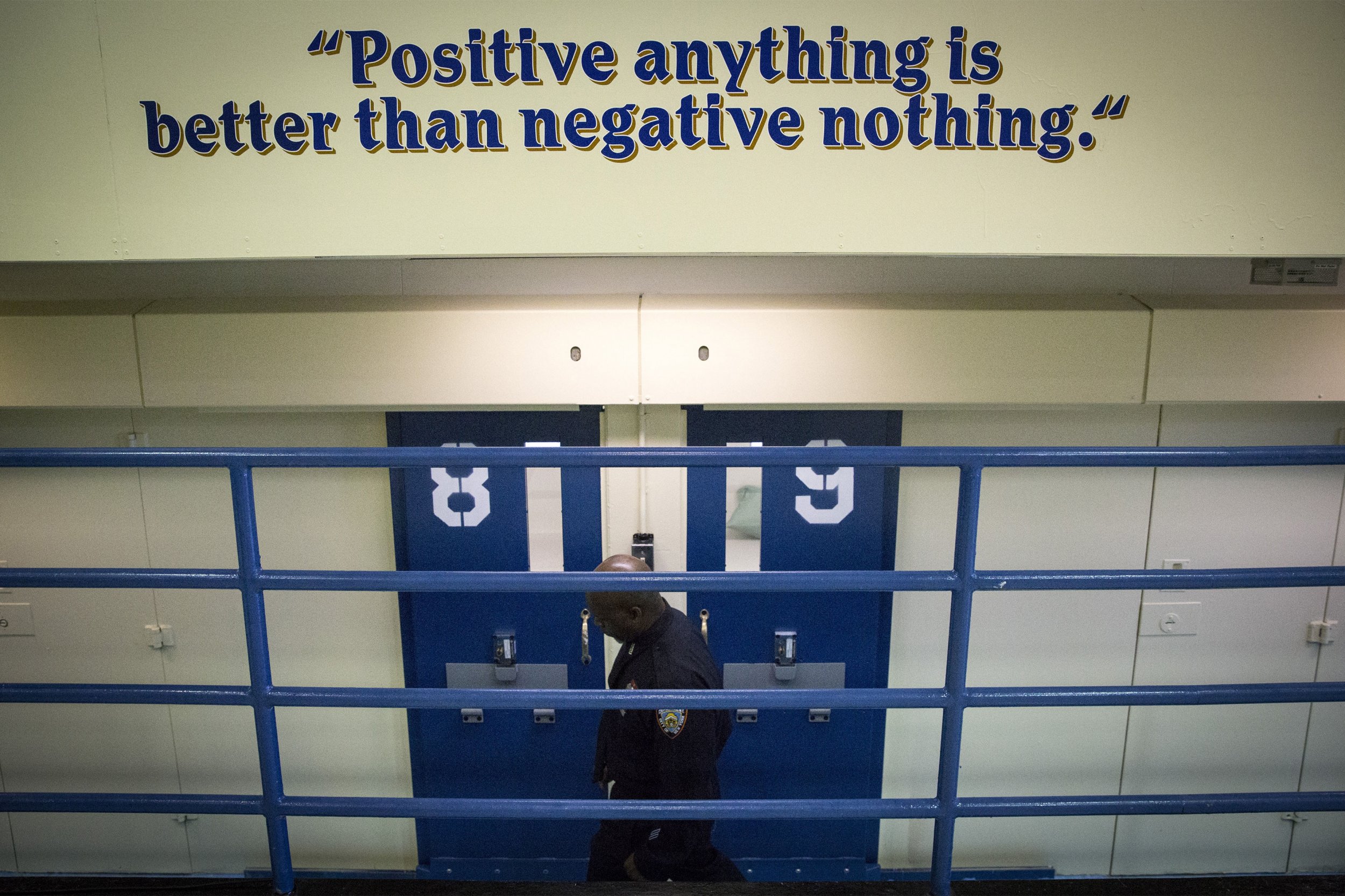

I try not to talk about best and worst, both because it's unfair to quantify pain—prison is prison, anywhere in the world, and all prison is pain—and because in many respects it's all relative; prison conditions often mirror, or are doppelgängers of, the societies in which they live. But I will say that two prisons remain seared in my memory as particularly painful. First, Jamaica's dreadfully overcrowded, frighteningly chaotic General Penitentiary, because I have spent a lot of time in Jamaica—it's a second home to me—so seeing the palpable suffering behind bars there was particularly haunting. And second—I don't explicitly visit it in the book, although my previous visits there are mentioned—Rikers Island, because it is a terrifyingly unsafe, ineffective human rights atrocity that thrives smack-dab in the middle of one of the most liberal, progressive places on earth.

Tell us about a single incarcerated individual who haunts your memory, and why.

At Pollsmoor Prison in South Africa—one of the largest prisons in Africa, where Mandela did time—I was part of a profound restorative justice workshop. I worked closely with a young man who was an avowed gangster, a member of the notorious Numbers Gangs. Over the course of the week, he came to grapple with the ripple effects of his actions; tried to reconcile with some of the people he had deeply harmed, including family members he hadn't seen in years; and also recognized the ways in which he has himself been victimized by structural racism, poverty and the legacy of apartheid.

I will never forget him or the growth he experienced. It's evidence of how much restorative justice can do in the name of justice, if we allow it to. He also haunts me because he reminded me so much of my incarcerated students in America: not some evil criminal but rather the product of systemic inequality, racism and poverty.

What does solitary confinement do to people, and can they recover?

I visited a federal supermax prison in Brazil, where most men were in solitary for 23 hours a day. It was one of the most frightening experiences of my life. I witnessed men going flagrantly mad, being traumatized by such an inhumane practice. Multiple studies have shown how deeply solitary damages the psyche in ways that are often unalterable; that is certainly part of why we are seeing so much attention paid to it now, particularly by President Obama, who has banned it for juveniles in federal prisons.

But I say solitary is a practice that needs to go across the board, not simply for juveniles. It has not been shown to make prisons safer—quite the contrary, actually—and it is a glaring example of cruel and unusual punishment. Like many broken aspects of our justice system, it's used it, I think, because we are lazy. And there is no room for laziness when it comes to something as profound and far-reaching as justice.

America's incarceration rate leads the world. What does that say about us as a nation, and what is the solution?

I think America has an allegiance to punishment that in many ways transcends logic. It's enmeshed in our capitalist ethos: an emphasis on "I" above "we" that produces a callousness, an excessive individualism and most of all a stubborn belief in the power of individual agency over and above systems and structures. This last notion allows us to tolerate extreme forms of punishment because we imagine that everyone has the power to make law-abiding, healthy choices, ignoring the fact that for centuries, certain populations have essentially been conditioned for crime, even manufactured for prisons.

Extreme individualism and a capitalist ethos produce many great things in the realm of creative innovation. But they also foster the very opposite of the communitarian spirit I witnessed in Norway, which has no room for mass incarceration and excessive vengefulness. It's no accident that the birth of the U.S. coincides with the birth of the modern prison; our identity as a capitalist democracy manifested in the growth of the prison system.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Nina Burleigh is Newsweek's National Politics Correspondent. She is an award-winning journalist and the author of six books. Her last ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.