After 22 years of raising an extraordinary child, I had no illusions about how profound autism could manifest. Until now.

As our family departed to Florida for Thanksgiving, I rejoiced in exposing Zack to the robust sunshine, penetrating heat and expansive pools he so adores. Although his perseverative vocalizations had recently amped with greater volume—"I want bowling, now! Bowling yes! Bowling now!"—I dismissed it as another turbulent wave that would surely subside.

Like the ocean, his autistic behaviors come in tides, some light and playful, some steep and harrowing, some crashing angrily on the sandy shore which quickly recede.

As soon as we set foot in our rental, my beloved son began unraveling before my very eyes into a child I no longer recognized. At 200 pounds of steely muscle, I know the damage Zack's capable of inflicting can be irreparable.

Letting out a piercing shriek, he sprinted over to an unadorned wall and punched it hard, the drywall easily cratering to his velocity as my stomach bottomed out. I tried desperately to coax him towards the pool, confounded by the sudden, unprovoked burst of rage, but Zack glared as if insulted, eyed a sturdy glass table, and rammed his fist squarely down the middle.

The shrapnel lay everywhere—dangerous and prickly shards of glass warned me that we were entering unknown territory. Over the next hours, Zack's rage heightened to the point he couldn't sleep, gripped by rabid insomnia so acute I had to immerse him entirely in a deep bubble bath where he remained for hours upon hours.

Then Zack did something unprecedented, he began recounting snippets of memories going back to his early childhood that only I could decipher. "Elmo show! Movie—yes, no yes!" I stared at him in terror, as a kaleidoscope of memories tumbled upon each other, as if the Rolodex of his memory was flung into air, cards roiling out of order, overlapping and tormenting him. One thing was irrefutably clear—my son had genuinely lost his mind.

Frantic, I paged his psychiatrist who reminded me, "I know you've been resisting this for years but it's time to consider more serious medical intervention."

"No!" I barked back with a strangled sob. My love for Zack is a sacred trust. I know him on a granular level, my knowledge of his idiosyncrasies so intimate, I will only consider the least invasive interventions to preserve his bodily integrity and autonomy. As we hung up I could hear the trace of regret in his voice, but I know what Zack needs, and what he doesn't need.

I know Zack needs serious help, but there's one option I won't consider.

To parent a profoundly autistic child is to operate in a state devoid of clear or correct answers. We managed to get Zack back home, literally kicking and screaming to the horror of fellow airline passengers. Despite being locked into exhaustion, I persuaded Zack to take a long walk on a secluded woodsy trail. I'd already emailed his psychiatrist asking for another emergency consultation but vowed not to interrupt his Thanksgiving holiday, the sole stretch of quietude to which he's entitled from the cascade of desperate parents paging him day and night with emergencies. Surely I can hold on a bit longer.

We arrived at a charming, tiny playground intended for the youngest children. Gratefully Zack leapt onto a swing which provided me with respite enough to obsess over options—Zack had already tried CBD oil, cannabis and antidepressants, all of which he eventually acclimated to before breaking through completely.

I know Zack needs serious help, but there's one option I won't consider.

In the periphery, I caught sight of a toddler, a beautifully dressed little boy who couldn't have been more than 20 months old. A new walker on wobbly feet, joyfully making his way over to the little slide as his mother looked on with beaming pride, pondering those benighted concerns that are the preserve of most parents—shall I jump in and steady him, or let him topple and get back up? I didn't feel even a hint of rancor or envy, just quiet reverence, like watching a fledgling deer stagger towards the milestone of walking.

Did I gaze too long or too adoringly? The next thing I heard was Zack gnarled shriek, "Mommy like boy?!" and in an imperceptible flash, he charged towards the child with his arms raised and a metal iPod clenched in an angry fist—a fist he intended to bring down hard on the child's skull.

The toddler froze, stunned in his little tracks. In his terrorized visage I saw the reflection of my son through his innocent eyes—a monster as real as any featured in children's books. What he couldn't know, what few apprehend, is that Zack is innocent too, held captive to ungovernable impulses, one of many fixtures of profound autism.

My body reflexively sprang into action borne of years of emergency interventions. Against the ambient broth of screams—from Zack, the child, his mother—I intercepted Zack's outstretched arm so the device landed squarely on my spine, the sharp blade of metal piercing me like a dagger. Tripping over my feet I tumbled to the ground where I lay hobbled, crippled and disoriented, my vision gauzy and wet, certain only of one truth—if I was awaiting a sign, surely this was it.

Like a strike of lightning, it was a sober realization—no half-measures will work. I wasn't helping Zack. I paged his doctor and asked him to immediately call in the antipsychotic which I'd pick up in an hour.

And now I have betrayed myself. I'm doing that which I'd sworn I would never, no matter how dire the circumstances. But I am unrepentant. My child is gone, buried under afflictions of autism, so if radical measures are the only way to rescue him, then radical measures will be taken. All along this turbulent journey, I have never felt as clear-eyed as I do now, and I'm suddenly grateful for that certainty. Sometimes it helps to hit bottom, nothing brings greater clarity.

Why had I been withholding this medicine needed to address Zack's dysregulation? Was it to protect him, or me? I know Zack is autistic but he's not that autistic, right? It's slowly dawning on me that my inner turmoil was not about the efficacy of the medication but my refusal to admit that my son is capable of life-threatening behavior.

Beneath the very real pride I have in Zack, I'd erected an impenetrable façade of pride in myself, too—my success in getting him past phobias, my unwavering dedication to his growth, my need to believe I could handle any distress without resorting to potent medicine. My hubris that my son wasn't so impaired deprived him of the medicine he needed to safeguard his life. Raising him on an antipsychotic is not stigmatizing, it's imperative to allow him to access the world on his own disabled terms. So now I cross the Rubicon, and we wait.

I'd been warned that it could take several weeks for the medicine to build up in Zack's system to therapeutic levels. I lay awake by his side all night and the following day as he slept, and by the very next evening the fever broke. Calm, restored, coherent, Zack leaned over towards me with a sleepy smile, "Thank you Mommy," he whispered, "Hi Mommy, are you ok?"

Tears flooded my eyes and coursed down my cheeks, "Zack!" I gasped, astonished at the sudden reversal, "Are you back?"

"Yes Mommy, Zack is back. Zack is back."

With that, he cuddled into the arc of my arms as I melted deliriously in relief and gratitude. Parenting a child like Zack means letting go of presumptions or absolutes, needless pride, or concern that others may judge or vilify my choices.

Sometimes we parents get so bogged down by reason that it blinds us to common sense. I did right by my child. I know it because my son is restored to his glorious, profoundly autistic self. My prince is no longer suffering in anguish he cannot articulate. My prince is safe.

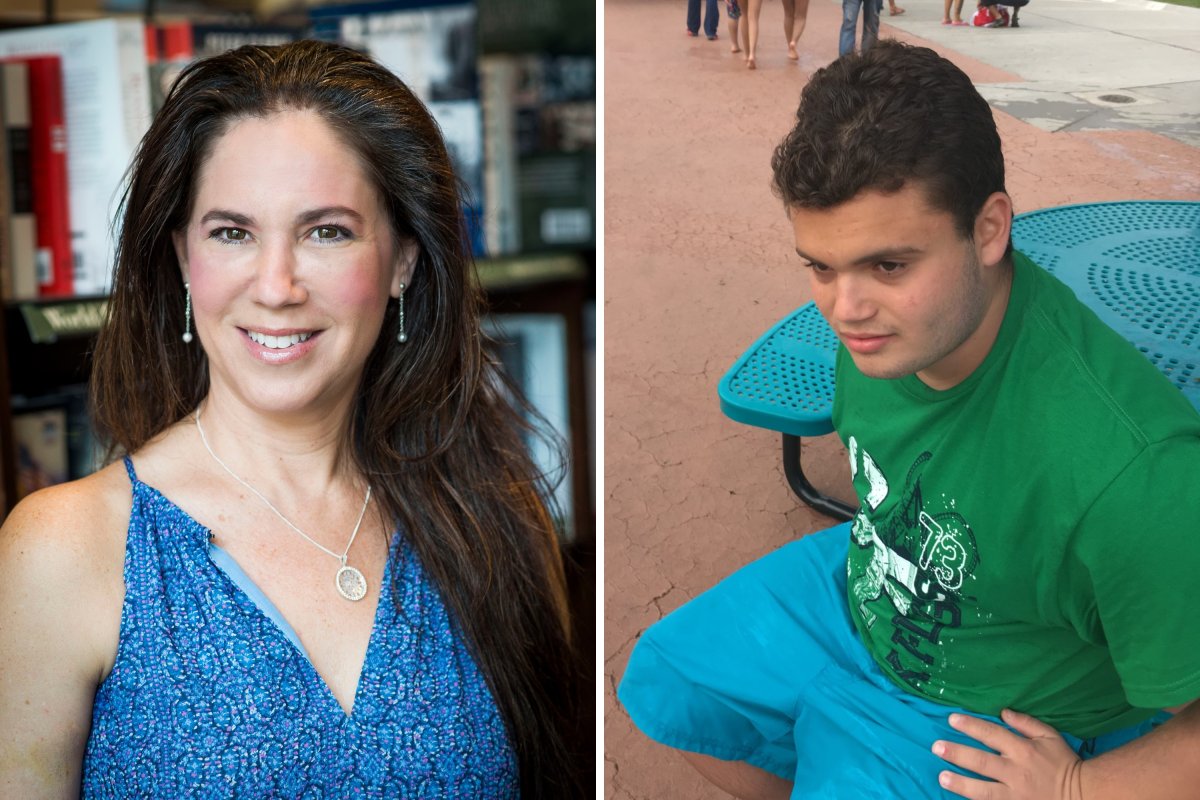

Whitney Ellenby is a former U.S. DOJ Disability Rights Attorney, author of the award-winning nonfiction memoir, Autism Uncensored: Pulling Back the Curtain (2018), and proud mother of a 22-year-old son with profound autism.

All views expressed in this article are the author's own.

Do you have a unique experience or personal story to share? Email the My Turn team at myturn@newsweek.com

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Whitney Ellenby is a former US DOJ Disability Rights Attorney, author of the award-winning nonfiction memoir, Autism Uncensored: Pulling Back ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.