For the past two years, while he was languishing in Tehran's Evin Prison, the world seemed to forget Iranian billionaire Babak Zanjani. But he returned to the headlines on March 6, when an Iranian court sentenced him to death.

Zanjani's story is that of a man who came from nowhere and amassed mind-boggling wealth providing illicit services to Iran's government, in the biggest publicly known money-laundering scheme in the country's memory. His demise was quick and brutal.

Zanjani had a solution to one of Iran's biggest problems. For years, he helped the government evade international sanctions against its nuclear program and sell oil on the global market. When the West imposed sanctions on him, his venture ended abruptly. After a change in government, he was arrested and accused of withholding $2.7 billion in state money. In early March, he got the death sentence for "corruption on earth," a catchall phrase for the most serious crimes against the state. Executions are usually conducted by hanging in Iran.

After his arrest in late 2013, I spent months tracing Zanjani's dealings, using Iranian media reports backed up by interviews with business sources, analysts and diplomats in several countries, including Iran and Malaysia. He also operated in Tajikistan, the United Arab Emirates and Turkey. In 2013, at 39, prior to his arrest, he bragged to an Iranian magazine, Aseman, that he was worth $13.5 billion and controlled a business empire of over 60 companies, including banks, airlines and cosmetic companies. Zanjani was not the only Iranian sanctions buster. But he was probably the best.

"In a way, this guy defeated the sanctions and helped keep Iran afloat in a very difficult set of economic circumstances. What he did was brilliant. He did it better than anyone else, he did it faster than anyone else," says Emanuele Ottolenghi, a senior fellow with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, who has studied Zanjani for years.

To some Iranians, Zanjani symbolized the cronyism and corruption permeating Iran's higher echelons. He paraded egregious wealth in a country where modesty is a virtue. While his countrymen choked under international sanctions—one week the currency dropped 40 percent; in another, the price of milk doubled—Zanjani flaunted Rolex watches and luxury cars and posed for photos inside a private jet.

Too young to have proved himself in the 1979 revolution or the 1980s war with Iraq, Zanjani took the only other available way to prominence and riches: cultivating close ties to Iran's Revolutionary Guard, whose grip on the economy tightened during Mahmoud Ahmadinejad's presidency. Weedy-looking and, by all accounts, affable, he mingled with a shady squad of characters that included Hassan Mirkazemi, a brutish regime insider known for beating Green Movement protesters in 2009, and Saeed Mortazavi, a former prosecutor accused of torture and murder.

Some saw Zanjani as a hero. He softened his braggadocio by sharing some of his wealth, providing million-dollar loans to struggling film directors and investing in a soccer club. Branding himself an economic basij—the name of Iran's paramilitary militia—Zanjani said he was doing God's work. In 2013, readers of two Iranian newspapers voted him third in Person of the Year polls, trailing only the new president, Hassan Rouhani, and the foreign minister. "Everything I did was with the help of God," Zanjani told Aseman magazine. "Miracles were happening in my life."

He was raised working class in the southern, traffic-choked part of Tehran, where motorcycles and taxis vie for space with street hawks and carts peddling vegetables and dried fruits. He became a jewelry seller in the bazaar, then a driver for the central bank governor who entrusted Zanjani with dealing currency in the bazaar. In the 1990s, with huge discrepancies between the market and official rates for foreign currency, this trade provided many young men with small fortunes.

Zanjani used these earnings to open an import business. But once established, he decided he would do greater things than trading in instant coffee and toothpaste. He has said his breakthrough came when he used his international connections to help Khatam al-Anbiya, an engineering company run by the Revolutionary Guard, receive orders of up to $90 million in oil sales. That got the attention of, among others, Iran's then oil minister, Rostam Ghasemi. With sanctions against Iran intensifying, the minister needed people who were able to move money, and willing to tie themselves to the government of the increasingly controversial Ahmadinejad. "This is especially a thorny issue since at least four major authorities during the Ahmadinejad administration, including the oil minister, central bank chief and economy minister, gave permission to Zanjani to sell oil, and they have remained mum about the issue," says Farideh Farhi, an Iran scholar at the University of Hawaii.

Zanjani operated through Sorinet Group, a conglomerate of some 60 businesses. When I investigated his companies in Tehran, I found some that were legit; others were plainly fronts. Few, though, seemed to be of a scale befitting a billionaire claiming to employ 17,000 people. One of Zanjani's sisters runs VIP Sorinet, an upscale restaurant serving Western indulgences like coq au vin—without the vin. She ignored my requests for an interview. When I drove to the outskirts of town, to an address listed for the Sorinet-affiliated Zanis Group, I found a three-story residential home with a simple metal gate and rusty water tank. From the balcony, a man in a singlet shouted he had never heard of the company. Other companies were little more than websites with crude illustrations and postings in broken English.

Sanctions-evasion networks are complex and opaque to obfuscate the identity of those in charge, says Ottolenghi. But perhaps Zanjani's smokescreens were always intended to also embezzle government money. "Zanjani may have used the same shell game designed to cover Iran's tracks from the prying eyes of the international community in order to blindside his Iranian paymasters," Ottolenghi says.

In early 2014, I traveled to the axis of Zanjani's empire: Labuan, a Malaysian island little known to outsiders. Its clientele probably prefers it that way, judging from the many lone businessmen and the solemnity of the streets, which look out over oil tankers sloshing in the waves offshore. It is the kind of tax haven where people don't ask too many questions. At the mention of Zanjani, many industry people nodded knowingly, but few divulged information. One industry source described Zanjani and his cohort like this: "It is a damn mafia."

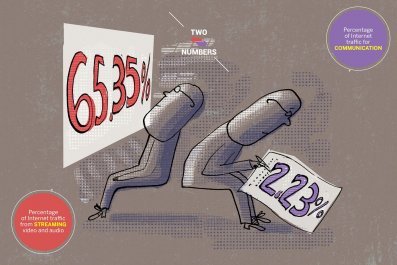

According to a Reuters investigation, Iranian ships in Labuan would transfer millions of barrels of oil in the dead of night to tankers sailing under other countries' flags. For the money part, Zanjani acquired stakes in the Malaysia-based First Islamic Investment Bank (FIIB). Iran was banned from using the Society for Worldwide Interbank Financial Telecommunication (SWIFT), the prevailing international banking system.

But Zanjani and Iranian officials could use FIIB's SWIFT codes to circulate money from Asia through Malaysia and onward to, for example, Tajikistan, where Zanjani had used a Turkish company to buy a bank. Onward to Turkey, where the money was converted into gold and smuggled into Iran, often via Dubai. There might have been other, similar schemes. In total, Zanjani has said he facilitated sales of 24 million barrels of oil.

Investigating the Iranian-linked businesses on Labuan constantly results in dead ends. In some cases, oil tankers were leased by a company called Glammarine, which according to Reuters was linked, by way of another shell company, to the National Iranian Oil Co. I tracked down a trust officer from the law firm ZICO, which represents Glammarine. He spoke on condition of anonymity. When I asked whether Glammarine had any physical offices, he said, "Not that I'm aware of." Asked if the firm had any employees, the officer said, "Not that I'm aware of."

Things began to unravel for Zanjani in late 2012 when the EU placed sanctions on him, FIIB and Sorinet. In April 2013, the United States followed suit. Constricted from moving money, Zanjani couldn't pay the government for oil he was handling. When the political winds in Iran changed, his luck finally dried up. In August 2013, Hassan Rouhani was inaugurated as the new president, after sweeping the reformist vote with promises that included battling corruption. Three months later, Zanjani was arrested and later charged with stealing over 2 billion euros.

He insists he has tried to pay the money back. His lawyer, Zohreh Rezaee, says the government gave Zanjani a year to settle his debts but arrested him four months before the due date. "It looks like a minister's promise is not valid in Iran. They may change their minds overnight," she tells me, calling the indictment "politically motivated."

"The fact here is that Mr. Zanjani was just a banker and businessman providing services to all Iran governments since the last 20 years," Rezaee says.

Zanjani's indictment is also part of a perpetual political power struggle in Iran. Zanjani serves as a fall guy for the current government's attempt, at least in public, to break with the cronyism of the Ahmadinejad era. However, Rouhani might not have intended the death sentence for Zanjani. The judiciary doesn't do the president's bidding. Zanjani's inability to pay his debts seems genuine. Zanjani himself may have been "sacrificed by the people who ended up with the money that cannot be traced, and used that money for other purposes," says Farhi.

Executing Zanjani won't get the Iranian government its money back. But it might put a symbolic end to an era. The sanctions that made Zanjani rich have now been lifted. On the same day Zanjani received his sentence, the first shipment of post-embargo Iranian oil reached Europe.