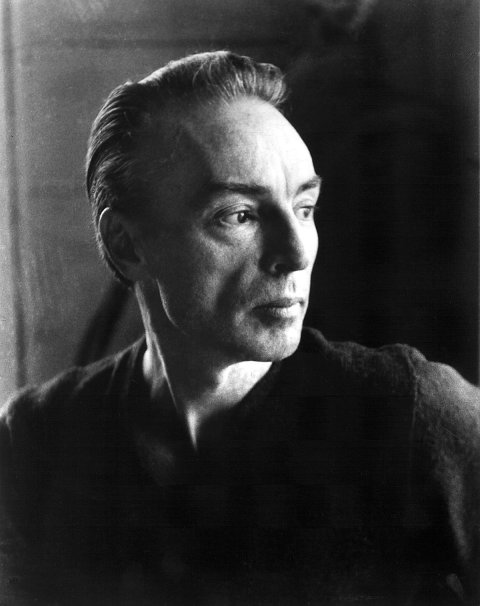

The greatest ballet choreographer of the 20th century had a favorite coffee shop, across the street from New York's Lincoln Center at the Empire Hotel. "Mr. B," as many called Russian émigré George Balanchine, would order a cup of coffee, or maybe a Beck's beer. It was here that he first told Jacques d'Amboise, then a principal dancer at his company, the New York City Ballet, about a work inspired by visits to the jewelry store Van Cleef & Arpels, called "Emeralds"—one of the three short ballets that would eventually make up the full-length Jewels. "You know, it's French countryside, like you see the impressionists paint—beautiful, warm, gentle and calming," Balanchine told his leading dancer.

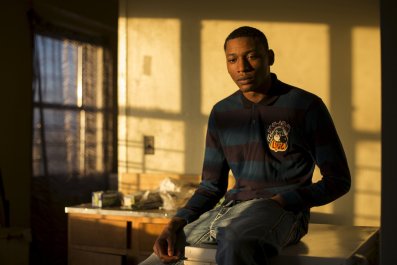

D'Amboise is telling me this 50 years later—complete with Balanchine's Russian accent and grammar quirks—from his office at the National Dance Institute in Harlem, which he founded in 1976. White-haired and brimming with energy, the 82-year-old continues his recollection: "And you know, second part of Jewels will be New York, 42nd Street at midnight, full of lights from the city, the blinking lights. And jazz, jazzy." That would be "Rubies," set to music by Igor Stravinsky, Balanchine's fellow émigré and frequent collaborator. ("Emeralds" is danced to a score by Gabriel Fauré.) Of the third and final movement, "Diamonds," with music by Peter Ilyich Tchaikovsky, Balanchine said, "It is the imperial court of the czar in Russia, St. Petersburg," the city where Balanchine studied dance and music and began his career. "Very elegant and grand."

This summer, the Lincoln Center Festival celebrates the 50th anniversary of Jewels with a historic production in the same theater where it had its premiere on April 13, 1967. In a historic collaboration, the New York City Ballet will share the stage with the Paris Opera Ballet and Moscow's Bolshoi Ballet for five performances (July 20 to 23). On opening night, the Paris Opera will perform "Emeralds," NYCB will take "Rubies," and the Bolshoi "Diamonds."

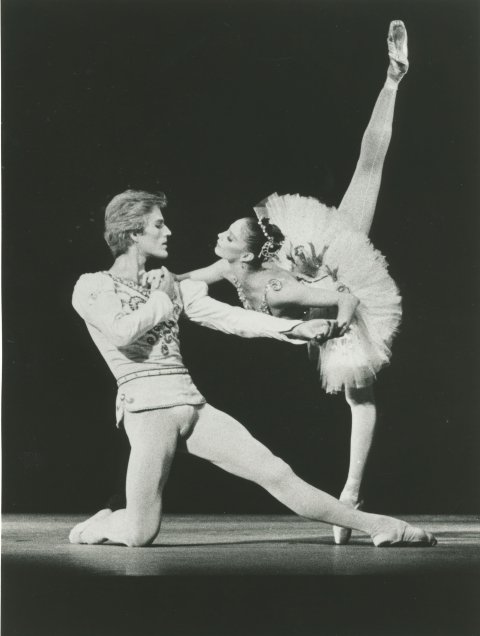

D'Amboise was the first to dance the lead in "Diamonds," alongside one of Balanchine's muses, Suzanne Farrell. He unfolds himself from his chair and, moving tentatively between his many bookshelves in a pair of scuffed white sneakers, marks the approximate motions of the main couple's entrance and of a variation that has since been cut. Later, he kneels to retrieve a diary marked "1967," flipping to the notes he'd scribbled down on April 12 and 13 of that year, tilting his head as he struggles to read his handwriting. "Stravinsky section was terrific, so is the rest of it I think.… Dress rehearsal. It was very good. Balanchine drooling at the mouth over Suzanne."

Jewels premiered unceremoniously on a Thursday night: There was no title in the program, just a blank space, because Balanchine had yet to finalize the name of the ballet. But the response to Jewels was momentous. "What Mr. Balanchine has here created is literally too beautiful for words," Clive Barnes wrote in The New York Times the day after the premiere, adding, "This ballet without a name is also without a story, and as such must be the first multi-act plotless ballet ever created."

Balanchine had revolutionized ballet; for the first time in a full-length work, the dance was all that mattered. "It's so much part of what we now assume about ballet that it's hard to go back there and say this was new then, because we now take it so much for granted," says Nigel Redden, director of the Lincoln Center Festival.

Peter Martins, current artistic director at NYCB, learned the lead in "Diamonds" from d'Amboise and first performed it in January 1968. The Danish dancer began performing as a guest artist just a few months after Jewels's premiere and joined permanently as a principal in 1970. He has his own story about the Empire Hotel coffee shop, this one involving tuna fish sandwiches, a glass or two of Aquavit and playing hooky from a "Diamonds" rehearsal. "You've done it forever, you don't need to rehearse," Balanchine told Martins.

Martins, who took over the company after Balanchine's death in 1983, considers Jewels to be "Mr. B's statement on classical ballet" in all its forms, including the romantic of the 19th century ("Emeralds"), the classical of Marius Petipa ("Diamonds") and the neoclassical ("Rubies"). Although Balanchine was a pioneer of the last form, he was a master of all three, with Jewels simultaneously a spectacle, an evocation of three captivating worlds that have clear moods (if not stories) and a primer in the history and styles of ballet.

The largely forgotten story of Jewels is that it was choreographed during the Cold War, when Russian and American relations were dangerously unstable. Ballet, with no language barrier, became a vital tool of cultural diplomacy: The Bolshoi arrived in the U.S. to great fanfare in 1959, and NYCB made its first trip to the Soviet Union in 1962 on a State Department–sponsored tour during the Cuban missile crisis. Balanchine possibly saw that potential in creating a ballet that featured a Russian and American story. With Jewels, "he proved that art has no borders," says Aurélie Dupont, a former principal who is now director of dance at the Paris Opera Ballet.

Five decades after the creation of Jewels, with the world facing new tensions, "there's an enormous importance in exchange," says Redden, who sees unlimited benefits to Russian, American and French dancers being able to share if not a language then a passion for ballet and Balanchine, as well as the stage.

Megan Fairchild, an NYCB principal dancer, will perform the lead in "Rubies" on opening night, and she believes this collaborative version will feature the "ideal cast [looking] its best ever." On opening night, she will head to the stage and test out a few turns and steps with her partner, Joaquin De Luz. Stravinsky is notoriously difficult to count—she says the "Rubies" score was mind-boggling when she was learning the piece—but she'll listen for the piano melody that serves as a marker, then run straight to center stage, where De Luz will lift her high.

Redden believes it will be one of those moments in an evening people never forget. And those who don't get in, he predicts, are "going to lie and say they did."