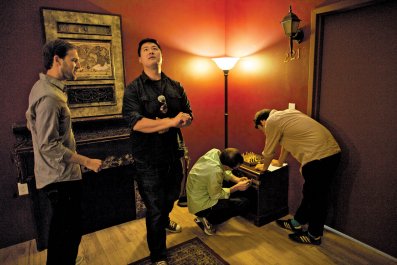

Several Eastern European countries have declared war on child protection agencies in Norway, Finland and the UK, claiming that they are breaking up families based on little or no conclusive evidence.

The issue has come to a head in Lithuania after a television chat show accused the Norwegian child protection services, Barnevernet, of seizing the seven-year-old son of a Lithuanian mother, Gražina Lešcinskiene, earlier this year, after the boy showed signs of "sexualised behaviour".

According to chat show An Hour with Ruta, Barnevernet routinely takes Lithuanian children from their parents as they are a "sought-after commodity" – a claim strongly denied by Norway.

The fall-out has become so toxic in Lithuania that the Norwegian ambassador there has hired a PR company to dispel the negative opinions of Norway being broadcast by the Lithuanian media. "This is a huge issue in Lithuania right now," says Daiva Petkeviciute, a Lithuanian living in Norway, who works for the Oslo-based group Human Rights House Network. "The first thing Lithuanians say when I tell them I live in Norway is, 'How do you still have your kids?'"

Meanwhile, a Latvian child living in the UK was removed from her mother in 2010 after the 21-month-old girl was allegedly found at home alone. The child was then placed with foster parents and is now living with adoptive British parents.

The mother denies her child was left alone and accuses the local authority of "forced adoption". Earlier this month the Latvian parliament issued a formal complaint to the Speaker of the House of Commons about the conduct of British social services. The head of the child affairs cooperation division at the Latvian Ministry of Justice, Agris Skudra, said Britain had failed to notify Latvia that the child had been removed from its parents, thus depriving relatives of being given the chance to care for the child.

"The only thing [the social services] have done is apologise for missing a significant step in the adoption process, but for the mother and Latvian institutions this is not a relief. Apologising and saying we didn't know something is not good enough," Skudra says.

There has also been growing anger in the Czech Republic over a case that occurred in 2011. The two sons of a Czech mother were removed by Norway's child protection agency after the parents were suspected of violence and sexual abuse. They were placed with different foster families. Earlier this year, Czech President Miloš Zeman accused Norway of "behaving like Nazis", and a petition that backs the mother has attracted almost 10,000 signatures. "In the eyes of Europeans, Norway has become a country that takes children away from their parents excessively," says Czech MEP Tomáš Zdechovský.

Wild theories circulating on Lithuanian social media suggest that Russian propaganda could be behind the discord. At the end of last year, the Russian Children's Right Commissioner accused Norway and Finland of "terrorising" Russian families living in Scandinavian nations.

Norwegian ambassador to Lithuania, Dag Halvorsen, says a care order is only taken as a last resort. He blames cultural differences for the crisis, an opinion echoed by Lithuanians and Norwegians alike, who point out that acceptable child discipline differs vastly between different countries and generations.

Indeed, the head of child right protection in Lithuania concurs that culture differences could be affecting cases but that they "understand the concern of the citizens of the Republic of Lithuania about the existing situation".

"With no clear legal regulation between these two states present, Lithuanian and Norwegian nationals have different interpretations of the situations when Norwegian authorities decide to curtail parental rights in their children's respect and to determine third-party custody of minor nationals of the Republic of Lithuania in Norwegian families. Information about cases like these is often published causing social frustration."

However, the Directorate for Children, Youth and Family Affairs in Norway says that they regret the "distortion" they believe certain media in Lithuania have created regarding the Norwegian child welfare system.

"Norwegian legislation is primarily based on one principle: The best interest of the child. The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most rapidly and widely ratified international human rights treaty in history, and Norway ratified the Convention in 1991.

The Norwegian Child Welfare Act's main purpose is to ensure that children who live in conditions that can harm their health and development are given necessary and adequate help and care.

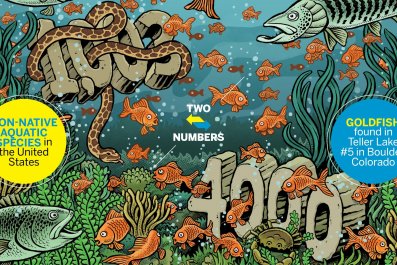

Regarding the Lithuanian population (including Norwegian born children from Lithuanian parents), less than 14 children out of a total of 5,906 children in Norway were placed out of home and 117 received voluntary support in the home."