On Friday at noon, America will bid farewell to Barack Obama's presidency as Donald J. Trump becomes the 45th president of the United States. Newsweek's first cover story on Obama, the man who would become the 44th U.S. president, described the newly elected U.S. senator as "a rising star who wants to get beyond blue vs. red," and as the man who would help his party relocate its moral core. The following story first appeared in Newsweek in its January 3, 2005 issue, and is republished here in honor of Obama's last day as president of the United States.

The Audacity of Hope

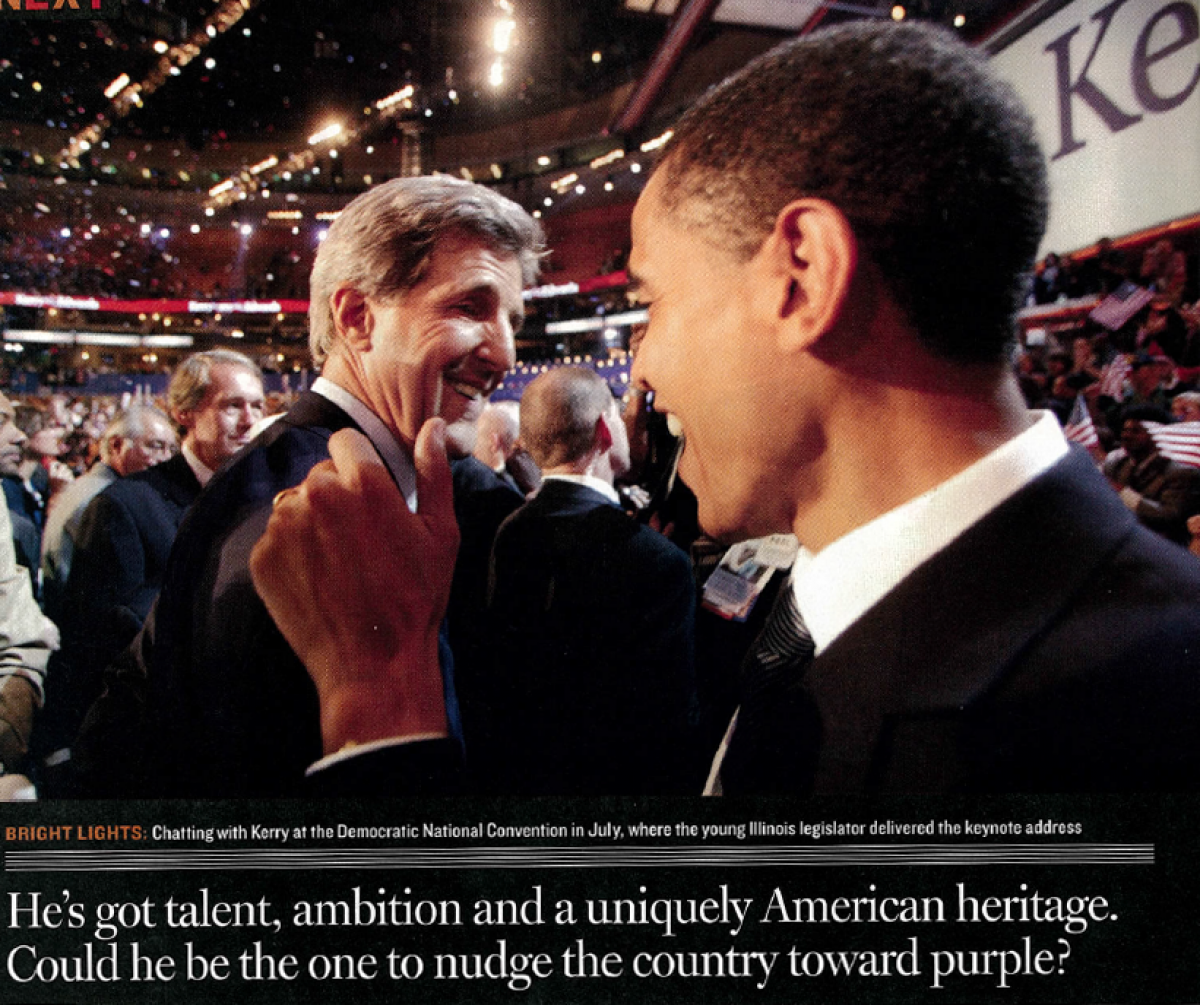

He's got talent, ambition and a uniquely American heritage. Could he be the one to nudge the country toward purple?

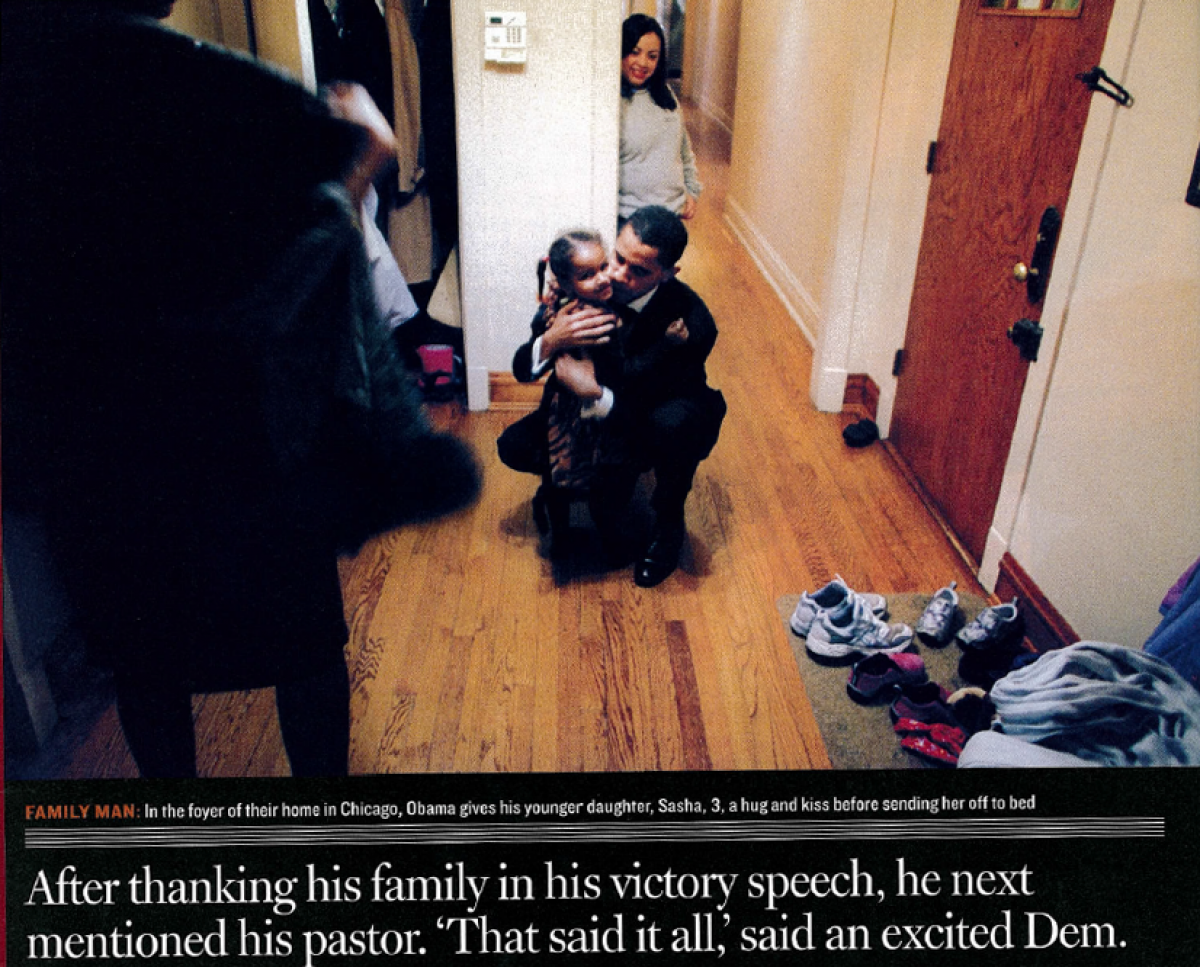

That first weekend after the election, Barack Obama and his wife, Michelle, decided to go see "Ray" at the movie theater in their Hyde Park neighborhood on Chicago's South Side. As they settled into their seats, a friend called out, "Barack!" and the audience turned around and began clapping. A few days later, when the Obamas went to another movie, this time with their daughters Malia, 6, and Sasha, 3, it happened again--sustained applause for the new junior senator from Illinois.

Anyone who has ever seen a senator in public knows that this kind of thing just doesn't happen outside of staged campaign events. In fact, when they show up at ball games, politicians are often booed. Obama--the self-described "skinny kid with a funny name" and first African-American male Democrat elected to the U.S. Senate--is unlikely to stay so popular, but he's already in a different category of fame.

A Tiger Woods category. A David Letterman and "Will & Grace" category (Grace said in a fall episode that she dreamed she was in the shower with Obama, who was "Ba-racking my world!"). A Robert F. Kennedy or Hillary Clinton comes-to-the-Senate category, where the national publicity upon their election exceeds that received by most senators in their entire careers. "I'm so overexposed I make Paris Hilton look like a recluse," Obama joked at Washington's Gridiron Club dinner in early December. "I figure there's nowhere to go from here but down, so tonight I'm announcing my retirement from the United States Senate."

Of course there's another direction to go than down, and desperate Democrats--viewing Obama's electrifying speech at the Democratic convention and landslide victory as about the only good news in a dismal election year--are already talking about him on the ticket in 2008. Although he will inevitably make most shortlists for vice president (and at 43, he's the same age JFK was when he was elected president), this speculation is almost comically premature for an incoming senator. But it does allow Obama to use what his Harvard Law School classmate Ken Mehlman, soon to be chairman of the Republican Party, calls his "star power" to work with the GOP on bridging Red-Blue divisions and getting some things done. The son of a black economist from Kenya and a white teacher from Kansas might be uniquely qualified to nudge the country toward the color purple.

"One party seems to be defending a moribund status quo, and the other is defending an oligarchy," he says coolly. "It's not a very attractive choice." Obama's a Blue State Democrat, all right, and by most standards a liberal one. But Illinois Rep. Rahm Emanuel, an architect of President Clinton's "Third Way" approach, sees him as a bridge from the left to the center of the spectrum: "Not just a phenomenal writer--he wrote that convention speech himself--but incredibly pragmatic."

Some party constituencies might be in for a surprise. Obama may be the only African-American in the Senate, but this is not a man who wants to be seen as the leader of black America. When he spoke at a Congressional Black Caucus reception recently, Obama graciously thanked several caucus leaders by name, then concluded with a short but telling statement: "I'm looking forward to working with you on behalf of all Americans."

But first he wants everyone to know that he'll be 99th in Senate seniority and "sharpening pencils" for a while. "I'm feeling very much like the rookie and looking for guidance from those who've been there for 15 or 20 years," Obama says with a ritualistic modesty he knows is expected of him now. He makes a point of saying that he'll be "listening and learning" from people like Ted Kennedy and Joe Lieberman, who know how to get things done in the minority.

To make sure he's concentrating on serving Illinois, he's turned down more than 200 speaking offers from around the world. Michelle doesn't mince words about the need for supporters to tamp down their inflated expectations of her husband, from unemployed workers in downstate Illinois looking for decent jobs to villagers in Kenya who think he'll bring them new schools. "Shoot, let people get disappointed right now," she says with a philosophical chuckle that owes more to her well-grounded upbringing on the South Side than her own years at Harvard Law. "They have to stop and think what's realistic."

Yet for a guy who a year ago was running fourth in some polls in the Democratic primary, "realistic" is a relative concept. Obama isn't cocky but he is confident, and fully prepared to step into a leadership role for the Democrats. Incoming Senate Minority Leader Harry Reid, who calls Obama "a gentleman and a scholar," expects him to travel abroad as a member of the Foreign Relations Committee and fit in well in the clubby Senate, where Obama has hired defeated Senate Minority Leader Tom Daschle's chief of staff to run his office.

That's the inside game. But Reid's wife noticed something on election night that helped the minority leader think about this new young senator in a broader way. After thanking his family in his victory speech, Obama next mentioned his pastor, the Rev. Jeremiah A. Wright Jr., of the Trinity United Church of Christ on the South Side, the African-American minister and community leader who first introduced Obama to "the audacity of hope." "That said it all," Reid concludes. "People don't know where he stands on issues, but they know he's an honest, God-fearing man."

It wasn't always so in the Obama family, as chronicled in his lyrical (if, by his own admission, overly long) 1995 memoir, "Dreams From My Father," now reissued and a best seller. Barack's paternal grandfather, a Luo tribesman who was raised wearing nothing but a goatskin loincloth, worked as a servant for British colonialists in Nairobi and converted to Islam before returning to farm on the shores of Lake Victoria. But the new senator's father, Barack Sr. (the name means "blessing from God"), had no discernible religious convictions. After growing up herding goats, he became the first African student at the University of Hawaii, where in 1959 he met an 18-year-old white girl from the mainland, descended from Cherokees, Baptists, Methodists, Kansas abolitionists and, indirectly, Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederacy.

Desperate Democrats--viewing Obama's electrifying speech at the Democratic convention and landslide victory as about the only good news in a dismal election year--are already talking about him on the ticket in 2008... this speculation is almost comically premature for an incoming senator.

Over the objections of their families (the white side was more accepting), they married, but when Obama was 2, his father left Hawaii, first for Harvard, then back to Kenya, where he worked for the government and was later killed in a car accident. He returned to Hawaii to see his son only once, when Barack was 10.

Barack, often called "Barry" inside his family, was raised in a secular home: "My mother saw religion as an impediment to broader values, like tolerance and racial inclusivity. She remembered churchgoing folks [in Kansas and Texas] who also called people niggers. But she was a deeply spiritual person, and when I moved to Chicago [after graduating from Columbia] and worked with church-based community organizations, I kept hearing her values expressed in the church." That tapped into "the hurt and pain" he felt as a fatherless biracial child and spoke to his sense of "the fragility and power and mystery of life."

The Democrats, Obama believes, need to speak to that power and mystery, too. He stops short of calling for a "religious left" to counter the political power of the religious right, but he wants the party to reconnect to what he sees as its roots in a moral imperative: "This shouldn't be hard to do. Martin Luther King did it. The abolitionists did it. Dorothy Day [of the Catholic Workers] did it. Most of the reform movements that have changed this country have been grounded in religious models. We don't have to start from scratch."

But Obama does call for a "new narrative" that simultaneously offers fresh solutions for problems like outsourcing (he hastens to add that he doesn't have them yet) and restores "timeless values." Unlike many liberals, he readily admits that a faction of the Democratic Party during the 1960s twisted the American tradition of individualism into "licentiousness" and rejected the party's older values of family, community and faith. Ever since, he says, the Republicans have caricatured the Democrats for ignoring these values, a line of assault that has proved especially effective because communal and moral values were exactly what gave the Democrats their advantage in the mid-20th century.

"In a recent 'Will & Grace' episode, Grace dreamed of being in the shower with Obama, who was 'Ba-racking my world!'

"They attacked our strengths," Obama says. When Democrats lost these deeper moorings, their economic message rang hollow: "People figured, 'At least with Bush, I can go hunt with my friends and my wife can go to church'," he says, adding that for men who remember hunting with their dads, say, or women who enjoyed going to church with their grandmother or granddaughter, these cultural concerns become family issues that cut deep.

Obama doesn't believe that John Kerry lost because of "moral values." It's much more complicated than that. But he knows that the cultural divide and issues like gay marriage and abortion played a role, and that Kerry actually lost among his fellow Roman Catholics. The task now, Obama says, is not to back off on any particular issue but to at least open these cultural subjects for discussion again--and for Democrats to "reclaim and reassert in very explicit language that our best ideas rise out of communal values."

Obama began that process in his now famous keynote speech at the convention ("We worship an awesome God in the Blue States, and we don't like federal agents poking around our libraries in the Red States"), which showed that an upbeat "One America" message still resonates. Running in the primary against white candidates, he did extremely well in heavily white areas. The experience of being cheered in Cairo, Ill., once among the most racist towns in America, was a breakthrough moment. This is not about "diversity" (a word he recognizes as horribly overused) but about embracing our hybrid origins and transcending our often narrow-minded past.

Even so, Obama's own rethinking of where the country should go still contains more questions than answers. How to respect entrepreneurship without allowing corporations to run roughshod? How to balance jobs at home with the benefits of globalization? In a new preface to his memoir, he's better able to describe what he's against than what he's for: "The hardening of lines, the embrace of fundamentalism and tribe, doom us all." Softening those lines won't be easy in today's fractious media culture, even with a unifying spiritual appeal.

And Obama remains concerned about how some Democrats may go about finding religion. "It's dangerous to try to engineer this in some synthetic way through the party. If it's not organic, it comes off as phony. People can sniff it out," he cautions. "Democrats have to say to themselves, 'What are the values we care most deeply about?' then do the hard spiritual work ahead of time. You can't every once in a while just throw in the word 'God'."

It's that idea of hard internal work--"soul-searching, no pun intended," he says--that seems to animate Obama. Even his most external qualities--his campaign-trail sociability and affable dealmaking--seem more the learned skills of a methodical thinker than the natural instincts of a backslapper. "He doesn't want to be this messianic figure carrying stone tablets," says David Axelrod, his campaign manager. "He understands he has to do the work."

Except for a couple of embittered slacker years at a Honolulu private school, this fits with his whole life story. Becoming the first African-American president of the Harvard Law Review--the pinnacle of distinction for law students--was not the product of affirmative action or popularity but of academic candlepower and unrelenting work. Hill Harper, an actor now starring in "CSI: New York," was a law-school classmate of Obama's who remembers his competitiveness on the basketball court and humility off it. He didn't carry himself like the big man on campus that he clearly was, though he remained confident enough to accept an offer to write a memoir when he wasn't yet 30. For everyone else, the point of getting on the law review was to build their resumes. Not Obama. "He could have easily gotten a Supreme Court clerkship and six-figure salary from any law firm," Harper says. "But he was committed to doing the work he wanted to do"--back in Chicago, back in the community.

Michelle, who met Barack in Chicago after law school, goes so far as to say that her husband "is not a politician first and foremost. He's a community activist exploring the viability of politics to make change." She and Harper both emphasize that there's nothing inevitable about Obama's running for president or even staying in the Senate if he doesn't feel he's making a difference.

Although he's emerging suddenly on the national stage, Obama has actually devoted himself to social change for nearly 20 years, first as a community organizer in housing projects, then as a civil-rights lawyer, constitutional-law professor and director of a huge voter-registration drive. There have been setbacks. In 2000, four years after being elected to the Illinois state Senate, he challenged incumbent Rep. Bobby Rush, a former Black Panther, for the House. This was a mistake, and Obama's support from white contributors outside the district didn't help. He lost with 30 percent of the vote.

But when Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. decided not to run for the U.S. Senate, Jackson became one of Obama's earliest supporters. (Jackson's sister Santita was a bridesmaid for Michelle.) After some early concern that he was aloof and "too white," suspicions of Obama in the Chicago black community have faded. It was no surprise that Alan Keyes, the black right-winger imported from Maryland to run against him in the general election, went nowhere. "Some people [still] say, 'The brother ain't gonna hang, he ain't gonna hold'," says Rep. Danny Davis. "But he has continued to express the needs of disadvantaged people."

"I'm so overexposed I make Paris Hilton look like a recluse," Obama joked.

Obama is realistic about the challenges of being in the minority party in Washington, but he got a lot accomplished in Springfield, even though the GOP was in control of the state Senate for six of his eight years there. Figuring that the Republicans were bent on tax cuts, he made sure the working poor got a big tax credit, too, and reached across the aisle to push through the first campaign-finance reform in 25 years in Illinois. "It really required someone who could set aside partisan differences and look for consensus," says Cindi Canary, director of the Illinois Campaign for Political Reform.

Later, in what he calls his biggest accomplishment, he sponsored a landmark bill that made Illinois the first state in the nation to require the videotaping of police interrogations. Emil Jones Jr., the Democratic president of the Illinois state Senate (and a man who confesses to crying during Obama's convention speech), says it was Obama's quiet legislative craftsmanship that broke the logjam with Republicans. The bill does more than eliminate the problem of coerced confessions. The admissibility of the videotapes in court helps "free the innocent but also convict the guilty," Obama notes, an example of the "win-win" ideas he hopes to pursue on Capitol Hill.

During the primary, Obama's expert grasp of foreign policy helped him bolt from the pack. He was an early opponent of the Iraq war, but made it clear he was against "this war, not all wars." (He supported the invasion of Afghanistan.) He focused on the growing problems of veterans and will also serve on that committee in the Senate. On domestic issues, his voting record will likely be to the left, which will presumably alienate some of the conservatives who told him over the summer how much they liked his speech. Certain alliances that were critical to his winning (for instance, a timely teachers-union endorsement) may make it harder for him to challenge Democratic Party orthodoxy.

The Obamas will be among the least wealthy families in the Senate. Barack says he must be one of the only members to prepare his own taxes (an incentive, he says, to work on tax simplification). Michelle, who launched the Chicago office of Public Allies, an innovative nonprofit that provides leadership development, now works for the University of Chicago Hospital and won't relocate to Washington just yet. Amid important meetings after the election, the Obamas found themselves at the hospital at 5 a.m. when one of their daughters couldn't stop vomiting. "They're working hard to be both good parents and providers," says Cindy Moelis, a family friend. "It puts them in touch with what most parents are going through."

Michelle's got it all figured out: "Giving a good speech doesn't make you Superman"--and she's willing to enumerate a few of Barack's faults. He started smoking again under the stress of the campaign, and still leaves his dirty socks on the floor. But that's about it. He's got a smaller ego and a greater appreciation of family these days, she says. After his major opponents in both the primary and the general elections dropped out amid sex scandals (though Obama would probably have won anyway), "people always ask, 'What's he got in the closet?' Well, we've been married 13 years, and I'd be shocked if there was some deep, dark secret."

His secret is of a different kind--not dark, not light, and maybe a tad intellectual for a country that doesn't like its politicians too smart. But it will soon be even more audible, from the well of the Senate and beyond. Some day it might even "Ba-rack the world."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.