Scientists have analyzed the stomach contents of a coach-sized prehistoric whale, known as Basilosaurus isis, for the first time, finding that it was a fearsome apex predator in its day.

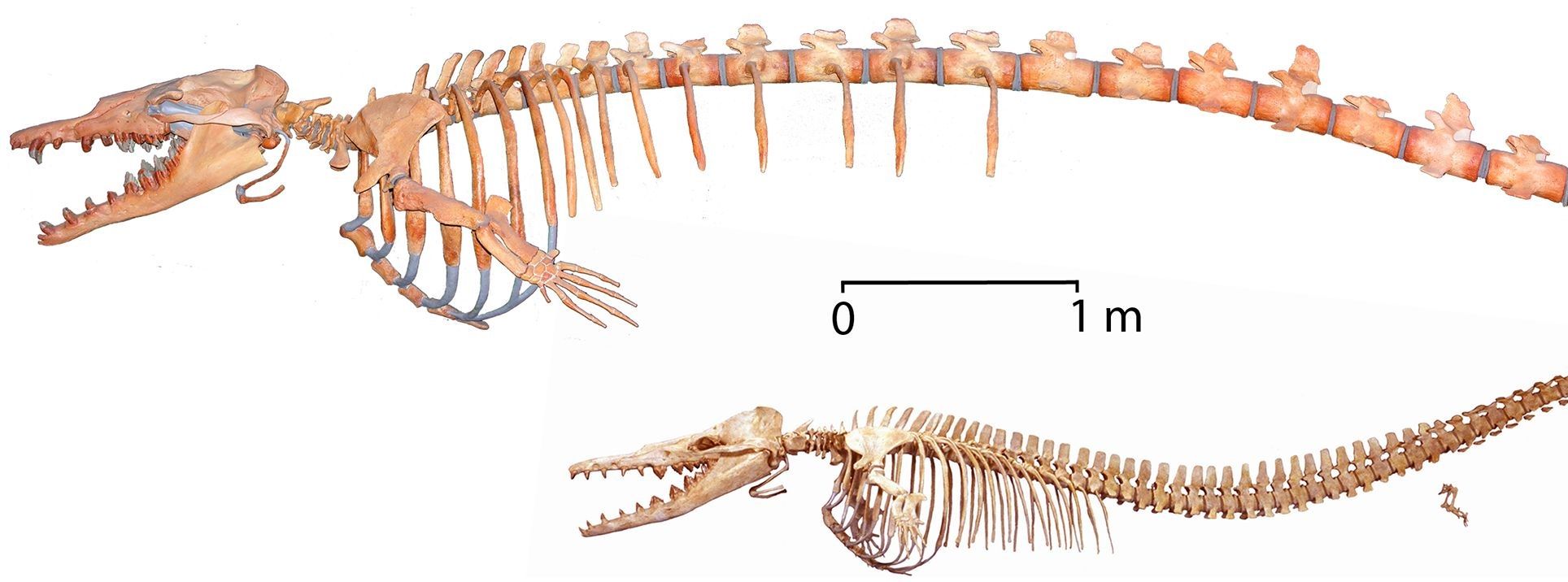

Now extinct, B. isis roamed the ancient seas between 38 and 34 million years ago when it would have been the largest whale of its time—alongside its sister species Basilosaurus cetoides—measuring up to 18 meters in length.

In 2010, researchers from the Museum für Naturkunde Berlin, Germany, discovered an intriguing adult specimen of B. isis at Wadi Al-Hitan, an important paleontological site around 90 miles southwest of Cairo.

Read more: Japan rejects ban on commercial whale hunting after 30 years despite international outcry

The UNESCO World Heritage Site—which was once a shallow sea— is known as the "Valley of the Whales" due to its extraordinary abundance of high-quality marine fossils, the remains of a wide range of ancient animals including rays, crocodiles and some of the earliest forms of whale.

Within the body cavity of the B. isis specimen, the German team found the bones of sharks, large fish and juveniles of a smaller species of prehistoric whale known as Dorudon atrox, many of which showed signs of breakage or bite marks.

In a study published in the journal PLOS ONE, they suggest that, given the available evidence, these bones represent the remains of animals that B. isis ate, indicating it was an apex predator that hunted its prey and not a scavenger.

"The find represents the first stomach contents found in B. isis, and as such reveals the first direct evidence for diet in that species," lead author of the study, Manja Voss, told Newsweek. "[This confirms] a long-suspected predator-prey-relationship of the two most frequently found fossil whales in Wadi Al-Hitan: 15-18-meter-long B. isis and 5-meter long D. atrox."

According to the study, several pieces of evidence led the team to this conclusion:

- The prey remains were clearly associated with the B. isis skeleton and found within the body cavity where the stomach could have been.

- Bite marks matching B. isis teeth were found on the head of the prey, an area of the body that the ancient whale preferred to attack.

- B. isis itself had a long snout and was armed with pointed incisors and sharp cheek teeth, indicating that the animal actively hunted.

"Apex predators live at the top of an ecological pyramid, preying on animals in the pyramid below and normally immune from predation themselves," the authors wrote in the study. "Apex predators are often, but not always, the largest animals of their kind."

"Lions, tigers, and large bears are commonly cited as apex predators on land," they wrote. "Orcas and great white sharks are commonly cited as apex predators in the sea. Most are large and achieve their dominance preying on smaller relatives."

According to the study, B. isis and B. cetoides were the largest known predators in the time that they lived, and they also rank among the largest of all the animals in the wider period between 66 to 15 million years ago, according to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History.

"Large body size, wide geographic range, and demonstrated predation on juvenile D. atrox, taken together, mark Basilosaurus as an apex predator in oceans of the late Eocene," the authors wrote.In light of their findings, the researchers propose that Wadi Al-Hitan was once a calving site for D. atrox and so it was likely a prime target for B. isis. This behavior is very similar to modern orcas which target humpback whales during their calving season.

This article was updated to include additional comment from Manja Voss.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Aristos is a Newsweek science reporter with the London, U.K., bureau. He reports on science and health topics, including; animal, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.