American Idol begins its 10th season this week without its star judge, Simon Cowell, who rode a penchant for cutting comments to international TV stardom. Last year Cowell announced he was quitting the show, walking away from one of the most lucrative contracts in broadcast television to run his own talent competition, The X Factor, which premieres in the fall. He'd threatened to leave for years, and Idol insiders say this became inevitable as far back as 2004, when the show's other Simon—Simon Fuller—sued Cowell in a British court.

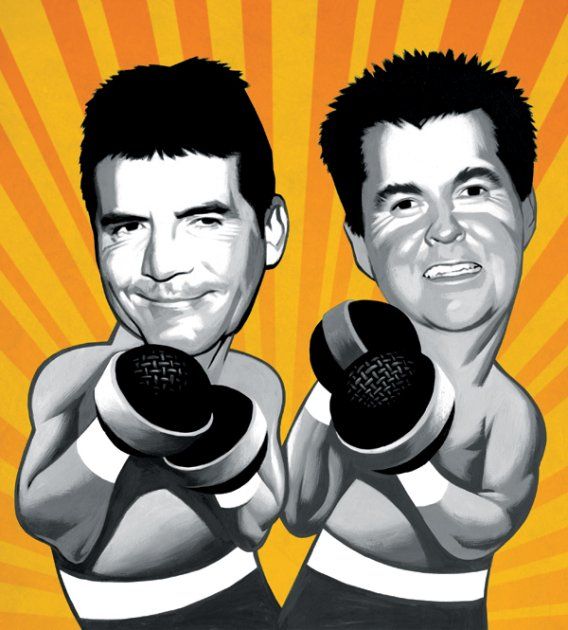

Longtime friends, then wildly successful collaborators, the two Simons are similar in many ways. A year apart in age, both sport flattop haircuts, and both worked at the "pop" iest edges of the U.K. music business. Beyond the shared name and the superficial resemblance, however, the two men are quite different. Fuller—shy, gracious, and wary of the limelight—muscled his way to success as an innovative outsider, building the first truly modern media empire around the Spice Girls, only to be summarily dropped as their manager in 1997.

Simon Cowell was a company man, a traditional A&R rep who rose quickly through the ranks at big record labels by focusing on profits over cultural cachet. While "most of my colleagues were obsessed with signing the next coolest rock or alternative band," he wrote in his 2003 memoir, Cowell scored massive hits with records based on WrestleMania, Teletubbies, and the Mighty Morphin Power Rangers.

But all those successes would be dwarfed by the format that Fuller created starring Cowell: a televised talent search called Pop Idol, then, when it emigrated, American Idol. After its 2002 debut, the American Idol franchise grew to draw tens of millions of viewers, and the show's contestants began selling millions of records. But after American Idol's smash third season, Fuller sued Cowell, alleging that he had ripped off the Idol format by starting the British version of The X Factor. "The battle between Fuller and Cowell that played out in the British courts—this was the undercurrent of everything that went on from the beginning of Idol," recalls a member of the team.

Sitting in his grand but subdued corner-office suite at the headquarters of Sony Music UK, Cowell spoke about the rift that eventually broke up one of the most successful partnerships in entertainment history.

"I didn't steal anything. I just made a new show as he made new shows," Cowell said while sipping ginger tea and dragging on Kool cigarettes. "At the point when Idol was launched, we both needed each other…I couldn't have done it without him, and I don't think he could have done it without me. But we both are people who like running our own businesses…It's been bizarre."

Yet nothing, surely, was more bizarre than the process by which Cowell, a behind-the-scenes record exec who professed he was "obsessed with getting rich," was transformed into an international television star.

It was Fuller who gave him the chance. Having been sacked by the Spice Girls, Fuller in 1999 pitched a talent competition called Fame Search to, among others, the U.K.'s ITV, eventual home of Pop Idol. It rejected the proposal, and Fuller moved on to other projects, but the concept of a massive talent hunt utilizing interactive technology wouldn't leave his head.

At the same time, a different U.K. televised talent competition called Popstars was looking to cast a "mean music critic" for its judging panel. A top choice was an eccentric, bombastic figure named Jonathan King, who was widely known in Britain as a singer, songwriter, producer, talk-show host, newspaper columnist, and novelty act. Unfortunately, when Popstars was in the planning stage, King was convicted of sexually molesting five boys between the ages of 14 and 16 a decade earlier.

Producer Nigel Lythgoe, who would eventually run American Idol, then turned to King's friend who had put up bail after his arrest—a little-known record executive named Simon Cowell. As it happened, Cowell had begun to knock up against the ceiling for an A&R man, yet he turned down Popstars—reluctantly, according to Lythgoe, because of a conflict with his label. But Cowell says otherwise. "I felt uncomfortable being on a show that would show people how the process actually works," he says, "and I didn't really like the idea of being on TV either."

Popstars was a huge hit, but Fuller watched and thought, "I could do this much, much better." His new idea, now called Pop Idol, aimed to let viewers vote on who got the recording contract. But he also wanted to cast a "mean judge." "Simon has been a friend of mine forever," he says. "So I called Simon up and I said, 'Look, I've got this idea. I need a partner in crime here.'?" Fuller and Cowell agreed that the Pop Idol winners would be managed by Fuller's company, 19, while Cowell and BMG would put out their albums. "My real interest at that point was having the acts on my label," Cowell said. "I had absolutely zero desire to be in front of the camera."

Until then, Cowell had made only rare appearances on the margins of the British tabloid culture. But just one month after Pop Idol premiered in 2001, the tabloid Sunday People zeroed in on Cowell under the headline WOMEN FANS FALL FOR MR. NASTY. "The record boss is being chased by besotted women wanting to get to know him better—despite his sarcastic comments and cutting remarks to young wannabes on the hit ITV talent show."

As his public profile rose, Cowell took action to manage his image. Over 40 when Pop Idol began, Cowell had had a handful of semipublic romances with singers and model types. However, his lack of a permanent partner, his friendship with imprisoned pedophile King, and a certain campy mise-en-scène—heavy on the famed skintight T shirts and high-waisted pants—all raised questions about Cowell's sexuality. Cowell hired a prominent public-relations specialist "for protection," he told The Guardian. But those questions have never gone away, and have only been fueled over the years by suggestive banter between Cowell and American Idol host Ryan Seacrest.

Not that it mattered. Pop Idol was the biggest thing anyone had seen since, well, the Spice Girls. And just days after the season finale in 2002, it was announced that Idol was heading to America—with its star judge. "We had seen footage and of course we knew for sure that Simon Cowell had to be there," says Mike Darnell, Fox's head of alternative entertainment. But Cowell nearly backed out, worried that his harsh persona would not translate to the more politically correct U.S. airwaves. "Then a friend of mine…called me and said, 'I think you're making a big mistake,'?" he says. "Because if it's a hit you'll wish you were on it, and if it's not a hit, you'll think you could have made it a hit.'?"

American Idol's season-one co-host Brian Dunkleman admits to having been extremely freaked out the first time he saw Mr. Nasty tell someone they should never sing again. "It's one thing to watch it on television, but then you spend time with these kids and you have to look at them right in the eyes, and then their mother is looking at you, like, 'What just happened?'?"

But Cowell's value was instantly clear. "I still didn't know what the hook of this show was—all these kids come out and sing," stage manager Debbie Williams remembers of her first day on the set. "Until he spoke, and then I said, 'OK. I get it now. That's the hook.'?" Simon would be the bad cop. Paula Abdul would be the good cop, and producer-musician Randy Jackson the amiable tie-breaker.

The American show, on Fox's 2002 summer schedule, was an immediate hit, and as the audience continued to grow over subsequent seasons, Cowell's putdowns grew richer, his metaphors ever more colorful. Joining his traditional "lounge singer" dismissal, he added "cruiseship singer," "wedding singer," and "rodeo singer" to his repertoire. "We were looking for spaghetti Bolognese and that was sweet-and-sour chicken," he told one befuddled contestant.

But it was soon clear that Cowell was not content to simply be "the talent." Looking back on those first seasons, he says, "It was hard, and that's the point, I think, where you have to say, 'Look, am I just a judge, or am I going into TV as a serious business?...I just didn't want to be a paid judge for the rest of my life."

When his X Factor launched on British television in October 2004, Cowell had two years remaining on his Idol contract. "The only thing the two talent shows have in common is Cowell," said Cowell about Fuller's copyright-infringement lawsuit against him. Casual observers, however, could be forgiven for noticing a more than passing resemblance between the shows. Like Idol, The X Factor began with regional auditions, building up to a series of live elimination rounds before three sharp-tongued judges. But there were major differences too. The X Factor was open to groups and to a much wider age range than Idol. More important, judges were not to serve as neutral overseers but as active mentors to the contestants, to the point of living with their charges during the show. The X Factor became a hit, and Cowell began talking with Fox about bringing it to the United States.

In the year that followed, Idol's fourth season, Cowell and Fuller went about their business, exchanging nary a word. And for a little while, there was some doubt as to whether—with the lawsuit unsettled—there would be a season five.

A leak to The New York Times from Cowell's camp in November 2005 stated that Cowell would leave Idol to start The X Factor for a rival network were his demands not met. Nine days later the parties in the lawsuit reached an agreement. Cowell was given a slightly larger stake in Idol; Fuller took some shares of The X Factor. Sony BMG, Cowell's label, would continue to own and produce Idol's albums. What's more, in exchange for Cowell continuing with American Idol, Pop Idol would be pulled off the air, conceding the United Kingdom entirely to The X Factor. London's Independent newspaper quoted one senior music executive as saying, "It has come out 75/25 in favor of Cowell. He is the star. He had all the aces."

But there was a catch, and a very big one indeed. In exchange for winning the airwaves in the United Kingdom, Cowell forfeited his dream of bringing The X Factor to the United States. In agreeing to serve as judge for another five years on American Idol, Cowell would spend the next half decade as just "talent" in America.

In the summer of 2009, with one more year left on Cowell's contract, there was a showdown with all the parties involved. Fox was represented by Rupert Murdoch himself, who offered a staggering deal: to continue his services on Idol as well as to bring The X Factor to America, Cowell would be paid in the neighborhood of $130 million a year.

The offer was so overwhelming, Cowell initially said yes. But he just couldn't do it. The desire to be the man with the name on the door was too great. "That's the time you find out that's who you really are, I guess," he says, looking back. "I used to say it's about the money…Suddenly, when you're in that position, loyalty comes into it, all sorts of emotions."

Finally, in January 2010, a visibly shaken Cowell appeared before the Television Critics Association meeting in Pasadena to say that he and Fox had reached an agreement that morning. "Where we have come to," he said, "is that The X Factor will launch in America in 2011, with me judging the show and executive-producing the show, and because of that, this will be my last season on American Idol."

At the Idol finale on May 26, 2010, a wistful Cowell looked out over the crowd one last time. "It felt very weird," he says, remembering the moment. "When you're standing there in front of 5,000, 6,000 people and you feel this warmth and emotion; that's when I felt more emotional than I ever thought I would feel. We've had this amazing run."

Excerpted from American Idol: The Untold Story by Richard Rushfield. Copyright © 2011 Richard Rushfield. Published by Hyperion. All rights reserved.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.