Brian Wilson, the lumbering savant who wrote, produced and sang an outlandish number of immortal pop songs back in the 1960s with his band, the Beach Boys, is swiveling in a chair, belly out, arms dangling, next to his faux-grand piano at the cavernous Burbank, Calif. studio where he and the rest of the group's surviving members are rehearsing for their much-ballyhooed 50th Anniversary reunion tour, which is set to start in three days. At 24, Wilson shelved what would have been his most avant-garde album, Smile, and retreated for decades into a dusky haze of drug abuse and mental illness; now, 45 years later, he has reemerged, stable but still somewhat screwy, to give the whole sun-and-surf thing a final go.

Before that can happen, though, the reconstituted Beach Boys must learn how to sing "That's Why God Made the Radio," the first new A-side that Wilson has written for the band since 1980. They are not entirely happy about this. Earlier, I heard keyboardist Bruce Johnston, who replaced Wilson on the road in 1965, talking to the group's tour manager about an upcoming satellite-radio gig. "Just so you know," the manager said, "Sirius wants you to perform 'That's Why God Made the Radio' tomorrow night."

"Oh really?" Johnston responded. "And how are we going to do that when we don't know it?"

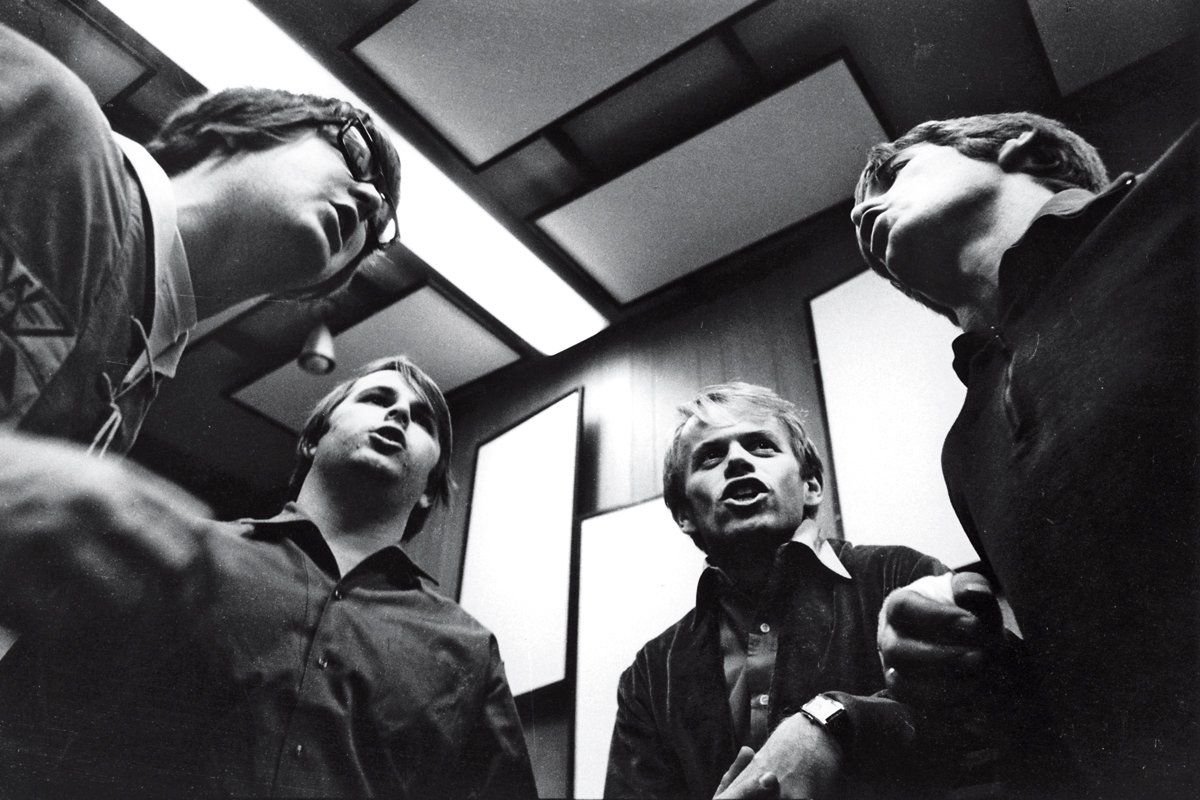

And so the band has gathered, once again, around Wilson's piano. I'd like to imagine that this is how it was when they first accustomed their vocal cords to, say, "California Girls." Except it's not, exactly: back then, in 1965, Wilson was the maestro, conducting each singer as his falsetto floated skyward and his fingers pecked out the accompaniment. Now he stares at a teleprompter and sings when he's told to sing, ceding his bench to one member of the 10-man backing band that will buffer the Beach Boys in concert and looking on while another orchestrates the harmonies and handles the loftier notes. At first, the blend is rough: Wilson strains to hit the high point of the hook; frontman Mike Love and guitarist Al Jardine miss their cues. But after eight or nine passes the stray voices begin to mesh. They begin to sound like the Beach Boys. Close your eyes, shutting out Wilson's swoosh of silver hair and Love's four golden rings, and 1965 isn't such a stretch.

Or it isn't until someone's iPhone rings. Jardine's. He turns away from the piano and presses the device to his ear. "I'm going to have to call you back, because--wait, what?" He hangs up, shaking his head. "Dick Clark just passed away," he says. The room begins to murmur; the makeup lady covers her mouth with her hand.

Over the next few minutes, I watch as each Beach Boy absorbs the news. Love makes light of it, pretending to strangle Jardine behind his back. "You're next, Al," he purrs. Johnston, a former A&R man at Columbia, pitches Clark's death as an angle for my story. "It's kind of ironic to have our television hero in music pass away while we're doing this next big move," he explains

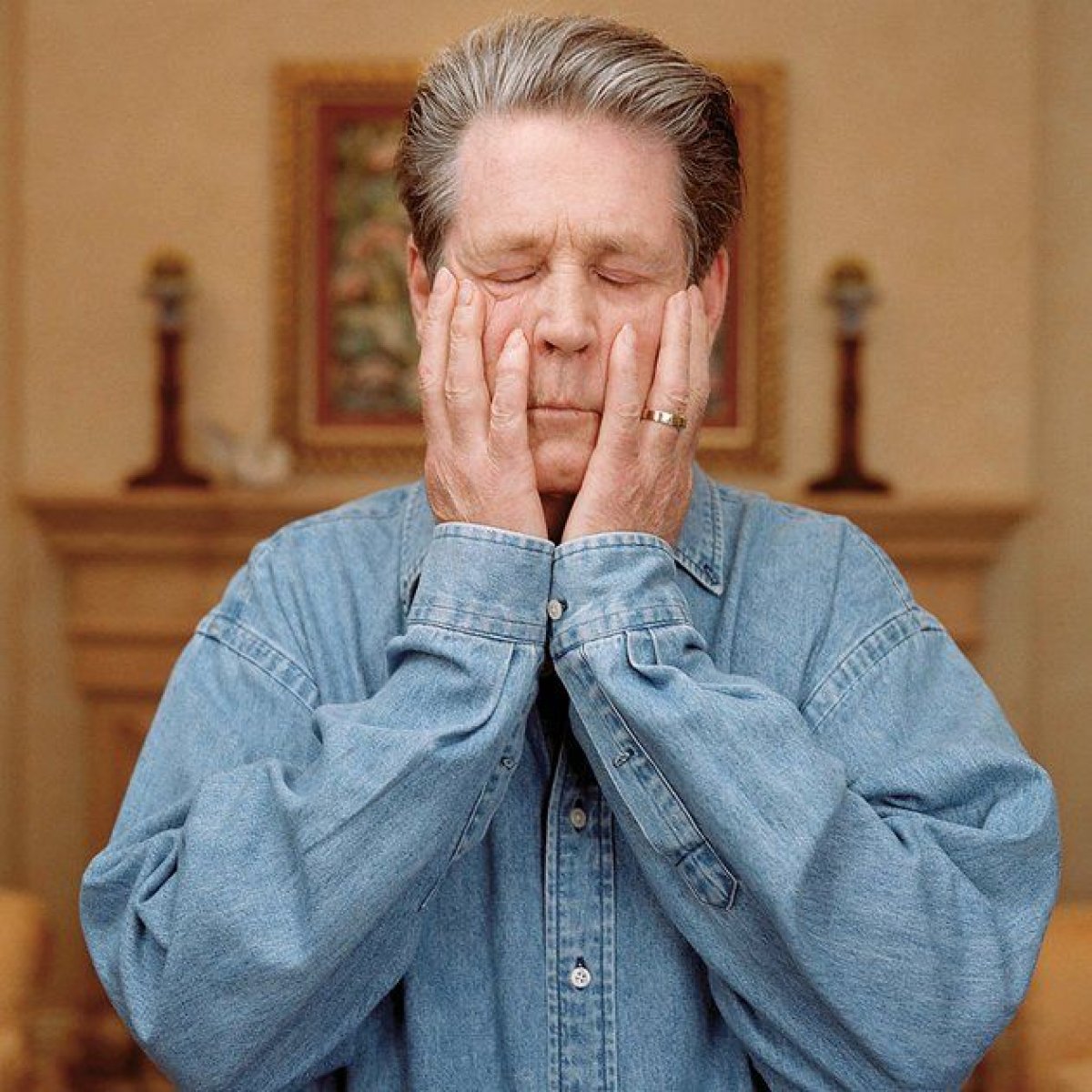

And then there's Wilson—always the conduit, the live wire, the pulsing limbic system of the Beach Boys. As his biographer David Leaf once put it, "Brian Wilson's special magic in the early and mid-1960s was that he was at one with his audience ... Brian had a teenage heart, until it was broken." At first, Wilson says nothing. Then I overhear him talking to Jardine.

"We're 70 fucking years old," he says. "You'll be 70 in September. I'll be 70 in June. I'm worried about being 70."

"It's still a few months off," Jardine says.

"That's true," Wilson mutters. He pauses for a few seconds, looking away from his bandmate. "I want to know how did we get here?" he finally says. "How did we ever fucking get here? That's what I want to know."

It's not a bad question. I have other questions, too, which is why I flew to Los Angeles to meet the Beach Boys in person, then continued on to concerts in New Orleans and New York, then spent weeks listening to their new album, That's Why God Made the Radio (out June 5). Why did we care enough about the Beach Boys to buy more than 100 million of their records? Why do we still care enough to snap up an estimated $70 million in reunion-tour tickets? Should we still care? Or is nostalgia all that's left? Also: what is it like to be America's first 50-year-old rock 'n' roll band? Is it morbid, or is it inspiring? Cathartic or embarrassing? Or is it something else entirely?

But "how did we ever fucking get here?"—that's the place to start. At some point, usually after Wilson appears on stage or on TV, every serious fan has been forced to answer The Question: "Wrong's wrong with Brian?" The suspicious eyes. The slack expression. The mirthless laugh. The slurred speech, often delivered out of the left side of his mouth. Lay people tend to assume he's had a stroke. I usually respond by reciting Wilson's clinical diagnosis: he suffers from schizoaffective disorder—sometimes, he hears voices—and mild manic depression, conditions that may or may not have been magnified and distorted by the LSD and cocaine he hoovered up as a young man and, more likely, the weapons-grade antipsychotics he was dosed with in middle age.

Still, after years of studying his past and obsessing over his music, I can't help but think that psychiatry and chemistry don't fully explain why Brian Wilson is the way he is. The reasons run deeper. My own theory is that he was never able, never quite allowed, to become a full-fledged adult—and that this, more than anything else, has been the story of his life, and of his band.

***

Set aside the biopic childhood of father Murry's relentless verbal and physical abuse, which left its own scars, and start instead with the just-as-formative musical adolescence that Brian lives through and mines, in real time, with the Beach Boys themselves. At 19, he writes his first song. It is not "Surfin'," the rudimentary ditty that the Beach Boys—cousin Mike Love on co-lead vocals; youngest brother Carl Wilson on lead guitar; middle brother Dennis Wilson on drums; high-school friend Al Jardine on rhythm guitar—will later offer a small L.A. label at their first recording session. He starts out far beyond that. Driving his '57 Ford to a Hawthorne hot-dog stand, Brian "puts [himself] to the test": can he can construct a melody solely in his head—no playing it on an instrument, no singing it out loud? He is surprised how easily it comes; he feels like an antenna picking up a distant signal.

An hour and a half later, he completes "Surfer Girl"—chords, harmonies, lyrics—at home on his piano. It is one of the most sophisticated first songs anyone has ever written: a kind of inverted doo-wop hymn full of minor sevenths and passing sixths that culminates in a swooning falsetto coda a half-step up from the original key. Still, for whatever reason--perhaps because of its unmanly lyrics, in which Brian imagines all the things he "would" do with a girl he can nonetheless never have—the Beach Boys wait two years before releasing their own version.

In the meantime, Brian churns out more than 20 Top 100 singles, many of which follow the beachy formula of "Surfin'." Mike enjoys writing lyrics about cars, girls, and surfing; as he will later put it, he is "into success." But success—the constant pressure of producing and performing—-begins to wear on Brian. He wants to grow. He tells a fan magazine that "probably my greatest motive for writing songs is an inferiority feeling, [like] I'm lacking in something." He says he often "feel[s] like an ant" and "must create something to bring [him] up on top."

On a flight to Houston, Brian suddenly starts to cry; soon he is "screaming and yelling" into a pillow. "I dumped myself out of the seat and all over the plane," he later says, as if he somehow left his body and floated through the pressurized cabin. He breaks down 15 times the next day, then flies home to be with his mother, Audree, who drives him to the now-vacant house where he was raised. There, he rants for three and a half hours, "dump[ing] out a lifelong hangup" and telling Audree "things [he'd] never told anyone." Neither of them will ever say what he revealed that afternoon. Days later, Brian decides to stop touring with the Beach Boys.

Subliminally, Brian has always channeled his apprehensions into his music; his "teenage heart" could never help it. "Don't Worry Baby" is supposed to be a song about drag racing, but it's actually a song about being afraid of drag racing, at least until "she makes love to me," as Brian puts it, and repeats the title phrase. The tidiest summary of Brian's genius might be the way the entire track shifts, imperceptibly, into a higher, happier key at that very moment, comforting the listener just as the singer's girlfriend comforts him.

But now, at home in Beverly Hills, away from the band, he deliberately writes songs about the changes he's going through. One, called "When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)," explores his anxieties about adulthood, with a contrapuntal coda that insists each passing year ("27, 28") "won't last forever." Another, "In the Back of My Mind," describes the downside of being "blessed with everything": that is, being "afraid it's going to change," too. Brian worries that his label and bandmates will balk, so he cuts some retro Beach Boys tracks, with Mike Love lyrics about the grooviness of amusement parks and Salt Lake City, just to keep everything copacetic.

And then, while the Beach Boys are on tour, Brian finally breaks free. He starts smoking pot. He tries acid, too, and hears voices. He stops; the voices don't. New, hipper friends filter through the house in Beverly Hills, and he hires one, a young, urbane copywriter, to be his lyricist. The ad man chooses the words, but Brian dictates the themes: the end of youth, the beginning of adulthood, that uncertain time in between. His new music, meanwhile, sounds more like "Surfer Girl" than "Surfin'," but it elongated, somehow, into these rapturous, revelatory shapes. "I'm gonna make the greatest album...ever made!" he tells his wife.

He recruits the finest session musicians in Los Angeles, and supplies them with the strangest instruments: bass harmonica, Theremin, banjo, water jug. He invents new, hybrid tones by taping two different instruments striking the same notes at the same time: a piano-guitar, an organ-bass. When the Beach Boys return to L.A., all that's left to do is sing. Still, on some songs, Brian records over his brothers and cousin so he can harmonize with himself; the blend is even more perfect like that. The album is called Pet Sounds. It begins with two lovers longing for marriage ("Wouldn't It Be Nice") and ends with a lament for a young girl's lost innocence ("Caroline, No"). It is the first LP of original Beach Boys material since 1963 not to go gold.

In time, the Beach Boys will come to appreciate Brian's grownup music, but they worry, at first, about its commercial appeal. "Who's gonna hear this shit?" Love says when Brian insists on rerecording something for the 30th time. "The ears of a dog?" And yet Brian forges ahead. His next project is Smile: a symphonic suite of interlocking songs and song fragments about Manifest Destiny, with Lewis Carroll-esque lyrics by another young hipster composer, Van Dyke Parks. The album's centerpiece is a plangent ballad about a "broken man" who escapes from the adult world—"the pretentiousness of everything," as Brian describes it—when he hears "a children's song." They call it "Surf's Up," as if to mark how far the Beach Boys have come since their own adolescence.

Brian's music is weirder than before, and so is his behavior. One day, he transforms his living room into a Bedouin tent; the next day, it is an exercise studio. The voices get louder: both the ones in his head telling him he's "going to die" and the ones in his band saying Smile won't sell. "Don't fuck with the formula," Love reportedly snaps. At a movie theater, Brian hears the characters onscreen speaking to him. Increasingly insecure and paranoid, he decides that it would be safer to shelve Smile than to knit its scattered threads into some sort of coherent whole. And so Brian Wilson's Sgt. Pepper--the album that would have established him as an adult composer—is locked in the vault, seemingly forever, and Brian himself is suspended between who he was and who he wanted to become. He will never be the same again.

***

"It's actually a miracle, to tell you truth, that the five of us are together and liking each other's company," says David Marks, who was the Beach Boys' guitarist for most of 1962 and 1963, and who has also joined the reunited band. "The chemistry picks up right where it left off."

This is the line Marks has been feeding to all of the journalists who have trekked out to Burbank to report on the Beach Boys reunion. Now the journalists are gone, and it's clear that Marks is only half-right. A miracle? Sure. But the chemistry still needs some work.

Watching Wilson rehearse, it's obvious that he is not used to performing with the Beach Boys yet. When the 50th Anniversary festivities were first announced, hardcore fans assumed that he had been forced, somehow, into reuniting with his old band: by his wife, by his accountant, by God knows whom. But the truth is that Wilson made the first move. While touring Australia in January 2008, he called Joe Thomas, the Chicago musician with whom he'd collaborated on his second solo studio album, 1998's Imagination. Thomas was shocked; they hadn't spoken in years. But Wilson had an idea. Back in 1999, Brian came up with a clever chord progression and gave it a memorably kooky title, "That's Why God Made the Radio"; Thomas and two other songwriters went on to add some lyrics and melody lines. They never finished the track, but Wilson "liked it so much," Thomas says, that he reserved it for the Beach Boys, just in case. Now he was wondering what it would be like to record it with them. When Thomas played "Radio" during a drive out to Palm Springs, Wilson "got really excited," according to the producer. By late 2010, the pair had coaxed an "incredible" offer out of Capitol Records for a new Beach Boys album. Love signed on first, and the rest of the band followed his lead.

Still, Wilson's original plan was to reassemble in the studio; the road is a more demanding commitment. Earlier, I asked if he had any misgivings about the reunion. "I was worried that I might not know how to talk to the guys, you know?" Wilson said. In what sense?"It's just a whole thing being with the Beach Boys," he mumbled. "It's a whole trip."

Now I can see what Wilson was getting at. The vibe in Burbank is collegial, but each Beach Boy is locked into his own orbit. Wilson and Love tend to communicate through the musical directors they've retained from their respective touring bands; Jardine, Johnston, and Marks hover on the margins. Over lunch, Jardine tells me he's been urging Love to open the second half of the set with "Our Prayer," the hushed choral prelude to Smile, but so far, Love has been brushing him off. "With him, you never know if it's confrontational or uncomfortable because he's able to mask any kind of negativity," Jardine says. "You never know if you've fucked up or not." When I mention "'Til I Die," a stark Wilson solo composition from 1971, Johnston, who's sitting nearby, insists that it was "the last Brian Wilson recording. Ever. The career ended for me right with that song." But why?"Because he was still 100 percent," Johnston explains. "Now, he's ... you know, a senior guy."

He's also a sphinx: stone-faced, inscrutable, cracked here and there. After five or six full-band passes at "That's Why God Made the Radio," Wilson changes the line "feel the music in the air" to "feel the Mu-ZAK in the air." The group's videographer laughs. "That's classic," he says. I've heard Wilson can be so passive that his aggression is almost imperceptible. Is that what's happening here? Is Wilson mocking the glossy new Beach Boys single? Or is he just being silly? Later, when the band decides to re-do "Good Vibrations," Brian objects. "I think we should move on," he says. But then, without warning, he begins to sing the song again, by himself. The band fidgets. "Brian Wilson unplugged, ladies and gentlemen," Love says. Finally, after a half a verse, Wilson's musical director intervenes. "Hold on, Brian," he says. "No one's with you." It feels like something I shouldn't be seeing.

The backing band sounds spectacular—no vocal or instrumental acrobatics are beyond them--and the Beach Boys themselves can still hit most of their notes. But they are tense enough when they're together, and inconsistent enough when they play, that it always feels as if they're about to fall short. The following weekend, the Beach Boys headline Jazz Fest in New Orleans. It's a blinding afternoon, and thousands of shirtless revelers fill the main lawn, reclining in beach chairs and sipping Miller Lite. I strike up a conversation with Pat "Estelle" Ritter, a 55-year-old restaurant worker. "I wouldn't have come if Brian wasn't involved," he says. "Otherwise, it's just a Beach Boys cover band, playing casinos. Brian Wilson is the Beach Boys." It's a nice sentiment, but over the next hour and a half, Ritter watches, with growing discomfort, as Wilson limps through the set. The giant video screens flanking the stage show him in various stages of distress or disengagement: kneading impassively at the piano; closing his eyes and swallowing between lines, as if continuing is chore; sitting out an entire verse of "Radio." When Wilson sings the famous "I want to go home" line from "Sloop John B," Ritter leans over and taps me on the shoulder. "Well," he says. "That kind of sums it up, doesn't it?"

Later that night, I run into a member of Wilson's band on Canal Street. "Good show," I say. "It was OK," he replies. "Brian was having a bad day." Apparently, Wilson woke up with a black eye that he couldn't remember receiving, then got his shoelaces caught in an escalator and fell "flat on his face." "It was the last thing this guy needed," the band member continues. "So we had to step in. Brian's the quarterback, and we're like the linemen. We have to protect him." You did an amazing job, I say; the harmonies were impeccable. He nods. "When my friends hear I'm touring with the Beach Boys, they're like, 'Oh, so you're doing fairgrounds and stuff?'" he says. "And I'm like, 'No, we're with Brian Wilson.' But, you know, when we performed Pet Sounds and Smile, that was art. That was Brian. Now we are kind of at the fairgrounds."

***

After Smile, Brian supplies the Beach Boys with the occasional song, usually two or three per album. They are always intriguing, but they are not like his old songs: not as ambitious, not as cohesive. Brian isn't in charge anymore; in fact, he's no longer sure he wants to be a Beach Boy. When the record label visits his house, he paints his face green. He gives away all of his gold records, "removing himself," as a friend will later put it, "from his own past." One afternoon in 1969, he bursts into the studio in his pajamas, waving a document in the air: a five-way contract that would change the band's name to "Beach." "We're not 'boys' anymore, right?" he says. "We're men! So why do we want to call ourselves Beach Boys?" The rest of the group refuses to sign it.

There are moments of clarity amid the confusion. In 1969, Brian writes a song called "'Til I Die." He ranges over his piano, searching for the right chords by keeping his thumb and pinkie in a set shape and moving only his middle fingers, internally. The progression he discovers seems to float between keys--an attempt, he says, to "emulate in sound the ocean's shifting tides and moods." Over three haiku-like verses, Brian compares himself to a cork on the ocean, a rock in a landslide, and a leaf on a windy day—small, helpless objects battered by vast, unfathomable forces. He thinks "'Til I Die" is the most personal thing he's ever written, but when he presents it to the Beach Boys, Love shrugs. Brian is devastated. He shelves the song for months.

Much of the 1970s, however, are a blur. Brian moves out of his Bel Air home and into the chauffeur's quarters; he rarely bathes or cuts his fingernails. He adds cocaine and heroin to his diet of drugs, which he ingests in bed for days on end. Most mornings he eats a dozen eggs and an entire loaf of bread; his weight soon tops 300 pounds. When Paul McCartney visits, Brian sobs softly to himself, refusing to leave his room; he forces Iggy Pop to sing "Shortening Bread" so many times that Pop flees in fear. After Brian's wife hires a celebrity "psychiatrist" named Eugene Landy, he gets stable enough, and thin enough, to rejoin the Beach Boys, who mount a massive "Brian is Back" PR campaign to capitalize on his return. But his sobriety is tenuous—during a Rolling Stone interview, he begs the reporter for cocaine—and his voice, now a croaking echo of his once-boyish tenor, is shot. On stage, he slouches at a piano, barely singing or playing, looking sweaty and scared. He manages to write and produce one real album, The Beach Boys Love You, a naked document of his neuroses. But the band rejects his (tellingly titled) follow-up, Adult Child, and he retreats, yet again, to his bedroom.

In Brian's absence, Love seizes control, transforming the Beach Boys into a pep-rally nostalgia act. They accept an endorsement deal with Chevrolet, rerecord "Good Vibrations" for a Sunkist commercial, and hire cheerleaders to dance on stage. Carl briefly quits, announcing that he'll only rejoin the group when "1981 means as much to us as 1961"; two years later, Dennis, drunk and depressed, drowns in the shallow waters of Marina del Rey. When Brian disappears for days, the band re-enlists Landy to look after him. The psychologist saves his life, but he also takes it over, dosing him with antipsychotic drugs, moving into his house, awarding himself composition credits, and writing himself into his Brian's will. At one point, Brian attempts to kill himself by swimming out to sea. And then, after eight years, a Santa Monica court orders Landy to stay away. "I can do anything I want to now," Brian says.

What Brian wants to do, it seems, is make music. As the Beach Boys splinter—Al leaves; Carl dies of lung cancer; Mike sues for unpaid royalties and exclusive rights to the group's name—Brian regains his footing, releasing several albums of original songs and performing Pet Sounds live with his crack new band. He still hears voices, but he "combat[s]" them "by singing really loud" and "play[ing] my instruments all day." In 2004, he finally completes Smile. It is hailed as a masterpiece. "I swear you could see something change in him," his engineer will later say. "And he's been different ever since." Asked about the Beach Boys, Brian doesn't mince words. "My new band is so much better," he says. "They play better and they sing better, too. I have much better time with them anyway."

***

There is a reason all these aging rock stars keep reuniting and touring: we keep shelling out for tickets. The Beach Boys are no exception. In 2011, Bon Jovi, U2, Take That, and Roger Waters topped the box-office charts with joint receipts of $821 million, and so far, 2012's live bestseller list—Black Sabbath, Bruce Springsteen, Van Halen, Madonna—isn't much fresher. Meanwhile, surveys suggest that the vast majority of all downloaded music is stolen, and album sales are half what they were at the turn of the century. We're witnessing a massive shift in revenue from new recordings to live music—and in large part it's live music that was originally released more than 20 years ago. The record industry is no longer a record industry. It's a touring industry for geezers.

This makes a certain kind of sense. Live shows are the last irreproducible, undownloadable experience a music fan can have, and the biggest ones will usually revolve around bands from back when bands could actually get big—that is, before our culture fragmented into a billion little niches. Still, the Beach Boys' performance in New Orleans raises some vexing questions. Is it enough for our favorite rock legends to show up, alive, and emit faithful renditions of their old recordings? To be there in the room with us, in person, as we enjoy a familiar soundtrack? Or should we expect more? Should we expect to be moved in ways that their CDs and MP3s can't move us? At JazzFest, there were plenty of Tommy Bahama-clad boomers who were happy to sing along to "Surfin' USA" and "Barbara Ann"—and even more happy to be able to say, afterward, that they had "seen" the reunited Beach Boys. But if you know the band's story, and if you care about Brian Wilson, then you want the Beach Boys to be more than a human jukebox. You want them to be a band again. And if Wilson isn't there—if he's off in his own head somewhere—then they can't really be reunited, can they?

A week later, the Beach Boys arrive at New York's Beacon Theater. I'm not sure what I'm expecting. Not much, at this point. The same cardboard nostalgia they conveyed at JazzFest; the same sad void where Brian Wilson should be. I'm quickly proven wrong. For the first few songs—"Do It Again," a bunch of the early surf tracks—Wilson looks as distant as ever. But then, on "Surfer Girl," something shifts: for the first time, at least that I've heard, he nails every note of that longing solo. He doesn't sound 19, but he comes closer, at 69, than anatomy would seem to allow. The crowd roars and leaps to its feet. It turns out that's all the encouragement Wilson needs. He launches into "Please Let Me Wonder," then "You're So Good to Me," then "When I Grow Up (To Be a Man)"—each lovelier and more alive than the last. Suddenly, he improvises a soulful little vocal riff: a signal, it seems, that he wants to play "Marcella," a rarity from 1973. "Thank you, Brian," Love says. "That was cool." After Johnston sings "Disney Girls," his only original in the set, he glances across the stage. "I learned it all from that guy: Brian Wilson," he says. Wilson beams back.

The high point, however, is "I Just Wasn't Made for These Times." Not because it is perfect—Wilson can no longer hit the highest notes, and he knows it—but because it isn't. When Brian wrote the song in 1966, it was about his budding ambition ("to look for places where new things might be found") and his fear of letting himself down ("each time things start to happen again... what goes wrong?") But now, 46 years later, "Times" sounds more ragged than before, and in its fragile beauty, it seems to be saying something new, something that every grown-up eventually discovers: that even when things go wrong—when your youthful ambitions don't pan out—you can still find your way back. The applause begins before the last note fades away. "Thank you," Wilson says, laughing. "Thank you. That's enough!"

Who knows what happened between New Orleans and New York. Maybe it was riding with Love in his Prevost bus, listening to '50s radio. Maybe it was all the massages his band members gave him, and all the times they said, "You're sounding great." Maybe it was seeing his wife, Melinda, in the audience. Again, who knows. But Brian Wilson was there at the Beacon. And so were the long-lost Beach Boys.

***

After the show, I return home and slip on my headphones. I received an advance copy of the new record, That's Why God Made the Radio, a few days ago, but I've been reluctant, until now, to listen. One reason is that Johnston already told me not to get my hopes up. "We're not here going, 'Oh, the album is going to go to No. 1," he'd said out in Burbank. "You listen to it and think, 'This is going to be great.' But it's not necessarily going to work out that way."

There are other red flags as well. None of the Beach Boys seemed very invested in the thing, for one. They'd recorded all of their parts in separate sessions; no huddling around the microphone, 1966-style. "All I had to do was sing, learn the songs," Johnston told me. "I didn't even have to write anything." The Beach Boys didn't choose the tracks, either—that was left to the executives at Capitol, who selected 12 of the band's 15 submissions. Many of the songs, meanwhile, were written way back in 1998 or 1999—leftovers from the first album Joe Thomas made with Wilson, and scraps from its unfinished follow-up—then culled from 800 hours of tape that had been moldering at Thomas's studio in Illinois. If it took Brian more than a decade to revive them, how good could they be?

But then "Think About the Days" begins, with its melancholy a cappella preface and arching falsetto line. It's gorgeous. When Thomas showed Wilson the chords, he devised the whole vocal arrangement on the spot, dictating each singer's part directly into Thomas's tape machine. "I could have played those progressions for 500 other people and nobody would have come up with that melody," Thomas says. It's a fitting start for the record: the first time the reunited Beach Boys gathered at L.A.'s Ocean Way studios, ostensibly to remake 1968's "Do It Again" as a trial run, Wilson sprung "Think About the Days" on them. Two hours later, the recording was complete. "Everybody walked out of there going, 'There's no chance we can't do this," Thomas says. "It was magic."

Nostalgic escapism dominates the first side of the record, largely because of Love. "Isn't It Time," one of the LP's five brand-new tracks, exhorts listeners to "dance the night away... just like yesterday"; "Spring Vacation," a rewrite of gospel number originally intended for Imagination, declares that "we're back together," "singing our songs" and "having a blast." Both lyrics are Mike's. "It was just like he told me 'California Girls' was," says Thomas. "Brian went, 'How about a title that's like "Spring Vacation, easy money?"' And within five minutes, Mike had polished it off." The other retro rocker, "Beaches in Mind," had a similar genesis.

The rest of Radio, however, isabout confronting the present rather than escaping it—and it is mostly Wilson's work. His finest songs—"Strange World," "From There to Back Again" (another new composition), "Pacific Coast Highway," "Summer's Gone"—close out the second side. According to Thomas, they form a suite of sorts: a "reflection of California from the standpoint of a guy who's almost 70 years old, driving down the Pacific Coast Highway and thinking about his life." I can hear echoes of vintage Brian, but more than anything else, this sounds like Brian Wilson now: "realiz[ing]" his "days are getting on"; "thinking about when life was still in front of" him; acknowledging that "old friends are gone."

Wilson's suite is so strong that it's tempting to dismiss the earlier, Love-inflected beach songs, and many critics will. But this is a Beach Boys album, not a Brian Wilson solo project. More than four decades ago, the band splintered because Wilson wanted to engage with adulthood and Love wanted to keep on celebrating adolescence. By doing both, and doing them well, Radio may represent a deeper reunion than anything that's happening on stage.

And it may not be the end. When Wilson wrote "Summer's Gone," back in 1999, his plan, says Thomas, "was to make that the last song on the last Beach Boys record." He even wanted to call the album Summer's Gone, in case anyone missed the point. But Wilson "had so much fun with Mike and the guys," Thomas explains, "that he insisted on changing the title. He didn't want the stigma that it had to be [the final LP]." Thomas claims that Wilson has more than enough material for another album, including "10 to 12 vignettes" that were edited out of the closing suite but "fit completely perfectly" together. "I'm hoping someday that it will come out in its entirety," he says. "The whole suite, as it was always intended."

As I restart Radio, I'm reminded of something Wilson once said about the voices in his head. "I can still hear things like, 'I'm going to kill you,'" he confessed. "Just usually negative thoughts or negative—"

The interviewer cut in. Ever hear them while you're singing?

"No, not when I'm singing, no."

When you're writing?

"No, not then, either."

When, then, would you hear them?

"When I'm not singing or writing."

If only he never had to stop.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.