A favorite film is defined by taste and emotion, the moment in your life when you see it and whether it lingers in your imagination. It is entirely personal. More tangible criteria define a great year in film: total box office, strides in ambition and innovation (whether it's storytelling, cinematography or special effects) and perceived cultural impact. In that regard, you'd have to include 1939, which yielded Gone With the Wind, The Wizard of Oz, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and Stagecoach, among many others. There's 1969 too, when Hollywood began to mirror the nation's deepening cynicism and mistrust of the status quo, as seen in the films Midnight Cowboy, Easy Rider, The Wild Bunch and They Shoot Horses, Don't They?

But is there a greatest year? Brian Raftery makes a good case for one in Best.Movie.Year.Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen (Simon & Schuster). The lifelong movie nerd was a young writer at Entertainment Weekly in 1999 (full disclosure: I was among his editors) when a cover story made that proclamation. After leaving EW, Raftery went on to write about culture for GQ and Wired. He also continued to inhale films, and over the next two decades he came to believe there was something to that cover line. After interviewing over 130 people for his book (among them, David Fincher, Reese Witherspoon and Christopher Nolan), Raftery realized he wasn't alone in believing 1999 to be Hollywood's best ever.

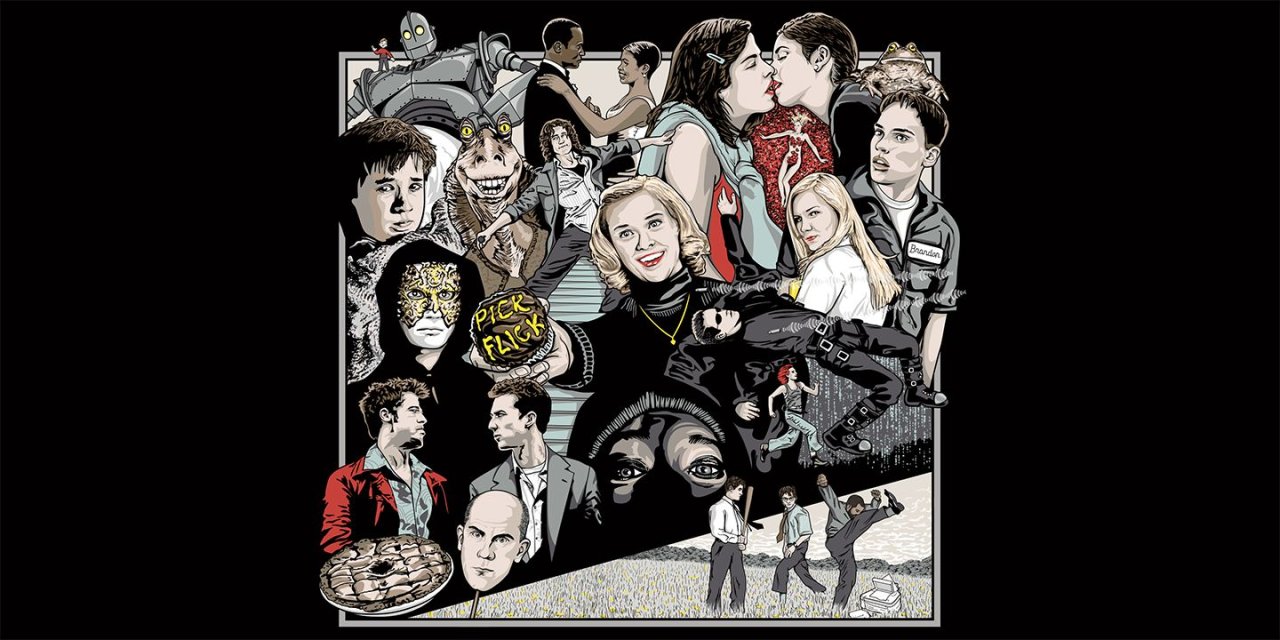

That year saw an astonishing breadth of quality and variety, from indie insta-classics Being John Malkovich (Spike Jonze's directorial debut) and The Blair Witch Project to box-office bonanzas like The Matrix and The Mummy. (It also saw the industry-changing launches of Netflix's monthly DVD subscription and Apple's AirPort technology.) Best.Movie.Year.Ever. is packed with trivia, behind-the-scenes anecdotes from creators, as well as Raftery's sharp, fair-minded and witty analysis—the culmination of over 30 years of an unwavering love for the big screen.

Let's get right to the argument: Why 1999 as opposed to, say, 1939 or 1969?

Those are extraordinary years! But 1999 felt like the culmination of everything that had come before, as well as a sneak preview of the future. Hollywood was in a strange place: Movies were still massive, but audiences were tiring of uninspired franchises, sequels and TV adaptations—like the infamously awful Batman & Robin. The big studios' momentum had also been eclipsed by the decade's indie-film boom. Even that movement was getting predictable, though. I worked in a video store in the '90s, and I can't tell you how many wannabe-cool, quirky dramas and lamestain Gen X comedies were pumped out then.

In 1999, you see executives, just as they did in 1939, start pouring tons of money and big stars into original, inventive, gotta-see-it-to-believe-it spectacles like the Wachowskis' The Matrix, David Fincher's Fight Club and even Stanley Kubrick's last film, Eyes Wide Shut. But they also turn to younger outsider voices—just like they did in 1969—which leads to David O. Russell's Three Kings, Sofia Coppola's The Virgin Suicides, Spike Jonze's Being John Malkovich and Alexander Payne's Election.

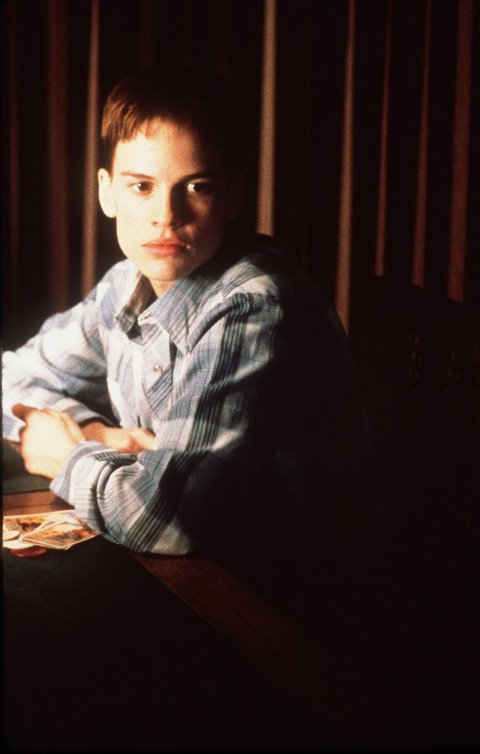

Mostly, though, I think of 1999 as a very idea-driven year, with the movies digging deep into pressing cultural and social problems, some of which we were just beginning to reckon with—like the thrill and terror of technology and our struggle with our identities and bodies. Some of them left you feeling pulverized, like Fight Club, or anguished, like Kimberly Peirce's Boys Don't Cry. But they were all trying hard to connect with the viewer on a very personal level.

Looking at the list of 1999 films, even the "lesser" offerings were satisfying and watchable, including Girl, Interrupted (with Angelina Jolie's Oscar-winning performance), Bowfinger and Dick. Julia Roberts had two big romantic comedies, Notting Hill and Runaway Bride. Someone out there is probably a Big Daddy fan.

Big Daddy is huge! It's still Sandler's biggest non-animated film. I had to exclude or cut many worthy movies for lack of space, including the documentary American Movie, The Straight Story, Dick, The Talented Mr. Ripley, the South Park movie and Deep Blue Sea—one of the last great big-budget B movies. There just wasn't enough room to properly explore super-smart sharks chomping Samuel L. Jackson in half.

Even further down the slate, you find things like Ravenous, this gnarly little western-slash-horror-movie that I remember being really wicked and smart.

You describe 1999 as a "culture rupture." Did that have something to do with it being the year before a new millennium?

Some of these movies—like Boys Don't Cry, The Matrix or Being John Malkovich—had been in development since at least the mid-'90s, so not precisely. But I also don't think these movies arrived at the same time by accident. Even though the last few years of the '90s were prosperous, the internet and 24-hour news contributed to a sense that we were radically speeding up, and that led to some anxious searching, like, "Wait, who the hell am I, exactly? What's my place in the modern world? Do I even have a place?" The "culture rupture" came about as a result, with concerns about how we live spilling into what we watched. It's why Cameron Diaz dives into John Malkovich's head, for example. The new millennium gave everyone an unconscious deadline for figuring their shit out.

You use the chapters to delve into industry trends. Were you aware of them at the time, or were they revealed as you watched all the films again?

I didn't fully put together just how many of 1999's movies were about white-collar dissatisfaction. It's not just Office Space—a breezy movie dealing with very real existential frustration; it's in The Matrix, Fight Club, American Beauty. Even Malkovich has this idea of escaping from the day-in, day-out drudgery of cubicle culture. That complaint might seem quaint in the era of WeWork and remote offices, but being overly defined or trapped by your job still resonates.

It's also striking how many of the movies deal with identity and the desire to literally be someone else. Obviously, that's in Malkovich, but it's also in Boys Don't Cry, Anthony Minghella's Ripley and smaller films like David Cronenberg's eXistenZ. That's why I can't buy that it was a coincidence that these movies showed up at once. Some communal unease was circulating, even if we couldn't articulate or recognize it then.

Puzzle box master Christopher Nolan brought his debut, Following, to Slamdance in 1999. And two other sanity-stretchers, as you call them, grabbed the glory at Sundance: Doug Liman's Go and Tom Tykwer's Run Lola Run. What made time-shifting so appealing?

I agree with Nolan's own theory that the advent of VHS, and later DVD, made viewers more comfortable with the idea of pausing and restructuring a story. But I also think the success of Quentin Tarantino's Pulp Fiction [1994]—not the first movie to futz with chronology but the first to make $100 million and earn a bunch of Oscar nods for doing so—gave filmmakers permission to screw around with narrative norms. And in the case of Go, Following and Lola, it helped that the directors weren't simply breaking up the narrative for fun: All of that timeline shifting helped it sprint along, especially in Lola; the storyline doesn't merely fracture, it starts all over again. It really teased the possibility of reinvention at a time when the idea of new beginnings was on a lot of people's minds.

Alan Ball's American Beauty won best picture that year, proving once again that the Oscars, at least in terms of legacy, are a crapshoot; Beauty, which also won original screenplay and best actor for Kevin Spacey, is widely considered one of the worst choices now. But you make a smart case for why it's better than people might remember.

I wasn't a fan when it was released—and made that clear in very obnoxious ways at many a holiday party that year. Later on, there was a lot of sneering: "Oh, this is just a big-screen TV movie." But having rewatched it several times, I've come to believe that the things that worked against the movie then have a posthumous power: A movie about a skeevy middle-aged guy and his Nazi-next-door neighbor might have seemed a bit much in 1999, but it's almost too timely now.

Speaking of timely, was there one film that, 20 years later, seems particularly prescient?

A few, actually. The not-so-soft misogyny that Tracy Flick [Reese Witherspoon] suffers in Election is something we're all more attuned to nowadays. Malkovich really gets at where we are with the internet: We can live vicariously through someone else, or even hijack their existence to a fairly terrifying and self-destructive degree. And the shits-and-giggles mayhem wrought by Fight Club's space monkeys reminds me of the way online harassment works: destructive, points-scoring battles with no ideology behind them, other than to bring something down.

But none were as forward-looking as The Matrix. The idea of taking the red pill versus the blue pill—one of which dropkicks you into reality, the other one shielding you from it—is something we do every day: Do I click on this story that I know will make me scared or angry, or do I click on the picture that will distract me? And the movie's notion that our machines are slowly overtaking us and draining us of energy—I feel that right now.

What other films did you come to appreciate?

It's more that the lens through which I viewed these films has changed. I loved The Insider when it came out, but I was mostly responding to it as a young movie nerd who wanted to watch Al Pacino and Russell Crowe butt heads. And also, probably, because it was a newsroom thriller—one of my favorite genres. Twenty years later, I appreciate the warnings it was raising about corporate malfeasance: It starts as a takedown of the tobacco industry and ends as a cautionary tale about the dilution of journalism by higher corporate powers. It was hard not to think of that while watching HBO's Theranos doc [The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley] and listening in as Elizabeth Holmes's lawyers tried, and failed, to intimidate a reporter.

The same applies to The Sixth Sense: In my 20s, it was a very cool mystery with good twists. As a parent, I see how much of it is about the primal fear we have about our kids: that, no matter what we do, we can't protect them or even fully understand their concerns.

So many of the movies of 1999 dealt with complex, existential concerns, and you grow along with them.

Including the teen movies. You devote a chapter to four box office hits—including the franchise-creating American Pie and Cruel Intentions. I can't imagine they were top of your list at the time.

Right. I was out of college and so not terribly interested in 10 Things I Hate About You or She's All That. But in researching the book I realized they all came out the same year as Columbine. These movies were, for the most part, very kind-hearted, empathetic and encouraging, and all were released at a time when being a teenager must have seemed terrifying. Sure, American Pie had a guy boinking pastry—and that will always be a draw!—but another reason might be that it reassured young viewers. "Don't worry, it's still okay to care about breakups and prom dates and getting laid."

Why a chapter on The Mummy? Yes, it made a lot of money, but is it groundbreaking or even good?

It's actually a pretty fun movie, but I paired it with Eyes Wide Shut because they both help exemplify a key reason why the Hollywood of 1999 feels so distant now: This was the era of the superstar actors who guaranteed huge opening weekends; because of that, they were granted massive salaries and power. Nowadays, the franchises are the marquee names. I like the cast of the new Star Wars movies, but if Episode IX only starred Gilbert Gottfried and a piece of toast, it would still clear $250 million in its first weekend.

In 1999, the big draws were stars like Mel Gibson, Harrison Ford and Tom Cruise, who was so valuable he could put all of Hollywood on hold for two years while he made Eyes Wide Shut with Kubrick. Or someone like Julia Roberts could make two $100 million–grossing movies in one summer. Studios were worried about actors getting too powerful, not to mention expensive. The focus became finding younger, more affordable talent. That's how you get Brendan Fraser, who had gone back and forth between indies and studio films in the '90s, being handed a massive summer blockbuster like The Mummy.

Twenty years later, how has the business of movies changed the most dramatically?

I'm probably the millionth person to point this out, even just today, but: There's no middle anymore. It feels like you have to make a film for either $1.5 million or $150 million. That's a simplification, of course, but the kind of system that could sustain $20 million to $70 million movies like Three Kings or Election hardly exists anymore. With so many viewing options available, and no more DVD market to help offset losses, the major studios need recognizable franchises and reboots—the movies people will go to on opening weekend, both here and overseas, and especially in the now huge market of China.

A few years ago, this was starting to get me down; it felt like the films that steer the cultural conversation were disappearing. But Jordan Peele's Get Out, Greta Gerwig's Lady Bird [both 2017], or deeply personal smaller movies like Paul Schrader's First Reformed—my favorite movie of 2018—prove there's still room for singular artists. And when franchise-moviemaking yields something like Black Panther, Mad Max: Fury Road or the last few Mission: Impossible films, it's deeply satisfying. I just miss the days when a filmmaker could get tens of millions of dollars for a completely new idea.

Are there 1999 films that wouldn't or couldn't get made today?

Nearly all of the major movies would have trouble getting that kind of funding. When Fincher was originally talking to Twentieth Century Fox about Fight Club, he said there were two ways of doing it: the supercheap "anarchist cookbook"–style version and the sleeker, big-star style, which is the one he wound up going with. Were Fight Club being adapted for the screen in 2019, it would be that scaled-down version. Maybe indie studios like Blumhouse would make it, or A24 or Annapurna, or maybe no studio would touch it, given the subject matter.

Or they would be made but not as movies. I could see Boys Don't Cry as a limited FX series; or Election—a really detail- and character-packed novel—as an HBO miniseries; or The Blair Witch Project as some sort of found-audio podcast experiment. People still crave these kinds of stories, they're just not always seeking them out in theaters anymore.

Right, so 1999 was significant for another reason: It saw the beginning of the creative shift to TV, with the debut of David Chase's The Sopranos on HBO. Turned out being able to say fuck on cable—among other things—would produce a golden age of the small screen. And that's evolved into an even smaller screen, and the only screen, of a new generation. I just binged Natasha Lyonne's Netflix series Russian Doll; it offers a radical pleasure similar to the films of 1999. Does it matter that it's not a movie?

I don't think it matters at all to younger viewers—many of whom, as you note, simply categorize everything that comes to them via a screen as the same species of content and don't have any TV-versus-movie hang-ups. I am crazy about television, and 20 years later it has definitely replaced movies as the higher power of popular culture. That said, I don't think any medium can be quite as immediate and impactful as film. A lot of the 2018 movies that knocked me out—Eighth Grade, Minding the Gap, Burning, Shoplifters—stayed with me for weeks, if not months. So as much as I fall into long relationships with TV shows I love, there's nothing like disappearing into a movie for two hours and never fully re-emerging.

What would be your pick for best picture of 1999?

I love Malkovich, American Movie and, even though it sends up a lot of red flags for some people—and not without reason—Fight Club, which was equal parts scarring and hilarious, a rare thing. But I vote for Election. I could give you a million specific reasons, from the script to the performances, but it's simply because it feels perfectly executed, in every way possible. And for what it's worth, a lot of the people I interviewed, including David Fincher and Sofia Coppola, put it at the top of their list, or very near it.

Desert island question: What five films from 1999 could you rewatch forever?

These aren't necessarily my top five, but for pure replayability: the South Park movie, because it's so catchy; Election, because it always feels like it was made yesterday; Malkovich, because it makes me laugh; Three Kings, because I find it so exciting—and because it's also stuck in a desert; and, I kid you not, the reviled-at-the-time Star Wars: Episode I—The Phantom Menace. I will be debating and rethinking that movie for the rest of my life—even if I'm all by myself.

And you know I'm going to ask: What's your worst movie of 1999?

To quote Dru Hill: I'm going straight to Wild Wild West.

Brian Raftery'sBest.Movie.Year.Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen will be published by Simon & Schuster on April 16. You can buy it here.