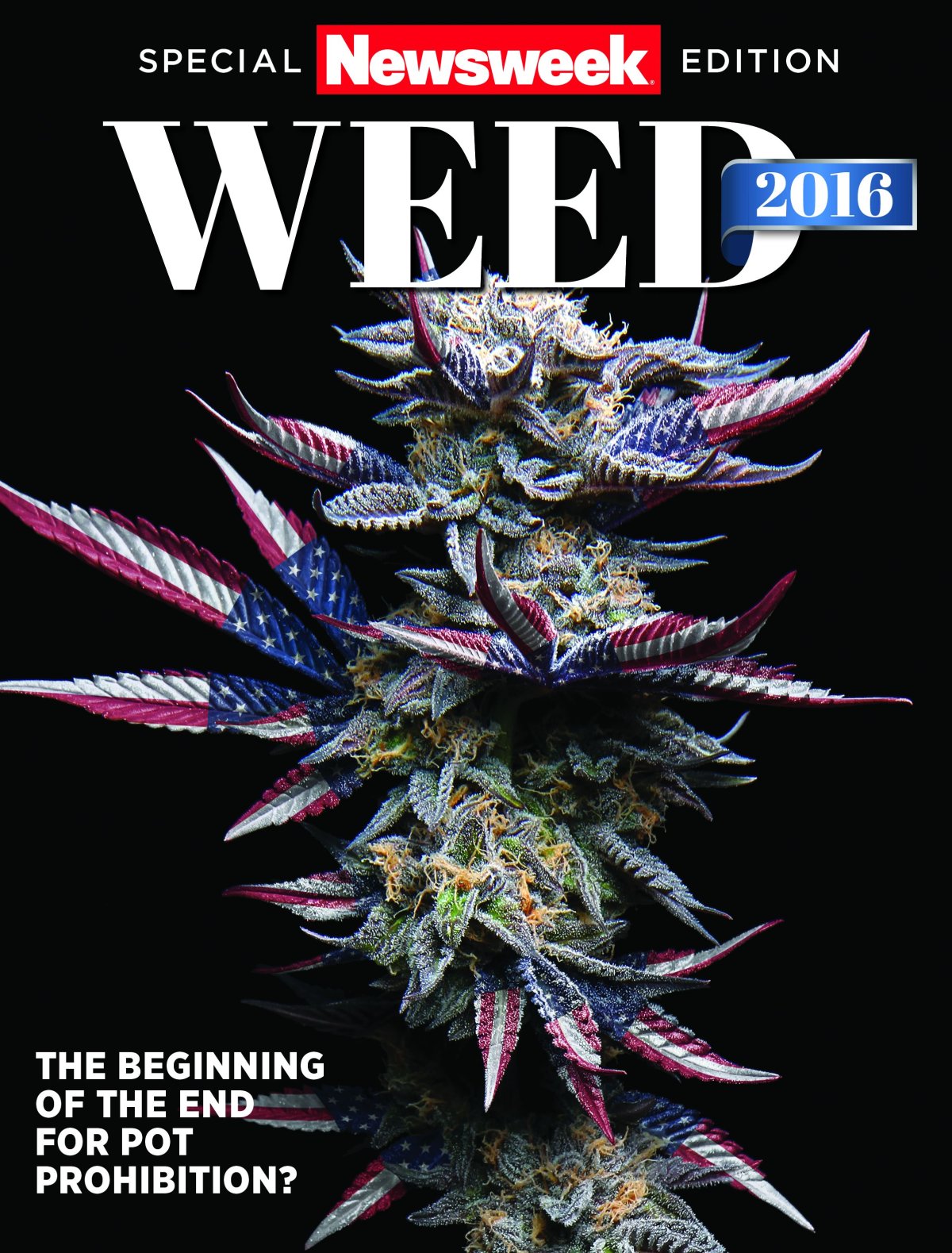

This article, written by Assistant Editor Alicia Kort, was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition, Weed 2016: The Beginning of the End for Pot Prohibition.

In the 1980s, scientists working for Pfizer set their sights on developing a drug for the pharmaceutical giant that would relieve hypertension and help save the lives of those suffering from angina. After years of tireless research by some of the best scientific minds money could buy, Pfizer created the chemical compound sildenafi l citrate in 1989. The company poured more money, time and talent into putting its new drug through clinical trials, only to discover sildenafi l citrate wasn't very effective in treating heart problems. However, men taking the would-be heart medication reported increased erections, and Pfizer decided to spin the drug's side effect into its main purpose. On March 27, 1998, the FDA approved sildenafi l citrate for public consumption under the brand name Viagra. Sale of the little blue pill swelled Pfizer's bottom line, with the company reporting more than $2 billion in revenue in 2012, almost 15 years after the medicine's market debut. The story of Viagra stands as one of the biggest successes in the history of commercial pharmaceuticals. With companies marketing drugs directly to consumers promising cures for almost anything, an increasingly destigmatized cannabis seems a likely target for the industry's next game-changing medicine.

But while the state-by-state legalization of medical (and recreational) cannabis has led to prescription-wielding patients availing themselves to strains of Purple Kush and Skywalker OG, significant obstacles discourage pharmaceutical companies from devoting the money and manpower needed to develop a marketable, patentable drug to take the plant's place. Cannabis sits on the federal government's list of Schedule I drugs—substances the government has deemed to have no medicinal value. For those tasked with creating new pharmaceuticals, this makes the already-laborious process of research and clinical trials even more arduous. The FDA, DEA and U.S. Public Health Service have to approve the release of cannabis to outside parties, and every bit of the plant has to be accounted for and secured, adding to the headache for those wanting to rake in a profit from pot. Even if a company created a drug, protecting the fruits of its labor with a patent is a dubious prospect at best. "You can't take a plant and patent it," Kenneth Kaitin, director of the Center for Drug Development at Tufts University, told Healthline in April 2015. "You'd have to have some sort of a process for isolating the active compound. But once you get away from product patents, the patent strength starts to diminish. Patents are progressively less and less of a protection because it's a lot easier to reproduce a compound using a slightly different process."

A few pharmaceutical companies outside of the United States have dipped their toes into turning cannabis into a product customers could find on the shelves of drugstores, most notably the British-based biofirm GW Pharmaceuticals. GW grows its cannabis in the U.K., where the legal restrictions have less of a stranglehold on researchers, and is in the processes of creating medicines based on that crop. Currently, the company's cannabis extract mouth spray Sativex is in the final clinical trials in the U.S. for cancer-related pain. Sativex received a patent from the United States Patent and Trademark Office in 2013, in part thanks to the federal government not officially considering it cannabis (even though the spray contains both THC and CBD). If approved and marketed, Sativex would follow in the footsteps of Marinol, a pill containing THC that doctors have prescribed to AIDS and cancer patients suffering from loss of appetite, which the FDA approved in 1985. But getting Sativex into the hands (and mouths) of patients is still years away, and the broader market for medicinal marijuana products lies untapped. Whether anyone will brave the inhospitable business climate and hazy legality of cannabis to create the next Viagra remains a mystery.

This was excerpted from Newsweek's Special Edition, Weed 2016: The Beginning of the End for Pot Prohibition, by Issue Editor James Ellis. For more on Marijuana in 2016, pick up your copy today.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.