"You tell all those white folks in Mississippi that all the scared niggers are dead." So said Stokely Carmichael at the birth of the Black Power movement in the 1960s. The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee organizer wasn't feeling so nonviolent after spending a few years watching police beat civil rights protesters with billy clubs in the South. With the Lowndes County Freedom Organization, Carmichael and other SNCC members tried to overthrow the all-white power structure running that majority-black Alabama county in 1965. They failed, but the group's symbol—a lunging black panther—endured, claws out, teeth sharp, ready to bite.

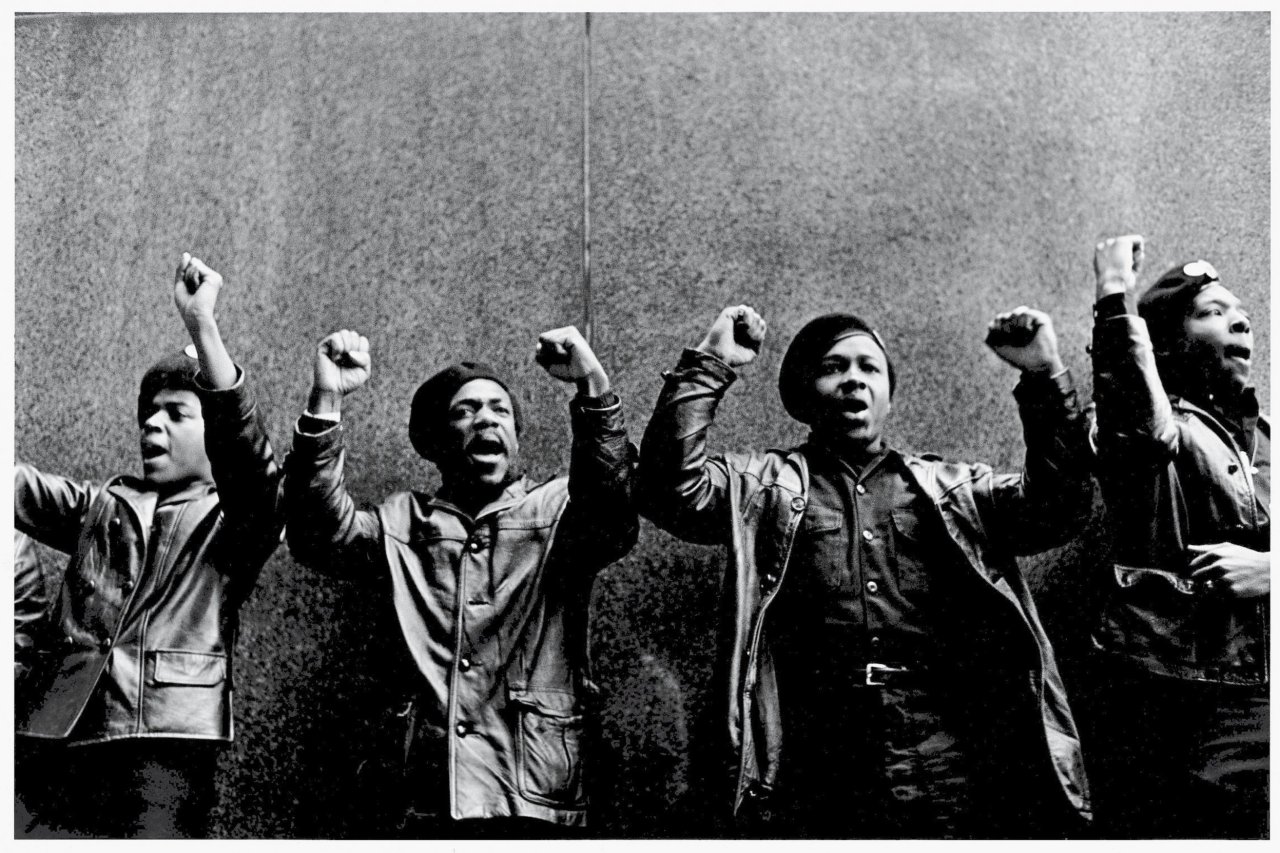

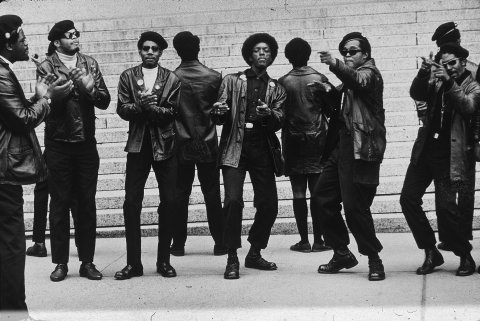

Google "Black Panther" today, and the first hit is the superhero slated for big-screen treatment in 2017. That Black Panther debuted in Marvel Comics' Fantastic Four in 1966—the same year Oakland college students Bobby Seale and Huey Newton founded the Black Panther Party, 50 years ago this October. Both superhero and mortal men took their name from Carmichael's ferocious feline, but the real-life Panthers had more style than the cat in the cat suit. The Afro, the leather jacket, the shades—that look has been referenced in films such as Forrest Gump and in Beyoncé's 2016 halftime Super Bowl show, where she and her dancers freaked out Breitbart News just by donning black berets. But the real Black Panther Party (BPP) was a lot more than superfly costumes. It was a group of utopian visionaries who sought to serve the oppressed and underserved communities not with guns (though they had those) but by demanding food, housing, education and so on. "There have been these blaxploitation cutouts [that stand in for] the way we think of these historical figures," says Alondra Nelson, author of Body and Soul: The Black Panther Party and the Fight Against Medical Discrimination. "These were human beings; they weren't angels. There's lots of complicated stuff. There was gun violence. People were murdered…. This was a complicated organization. But there's still lots we don't know about the breadth of the party."

That was, in part, by design: Early on, the FBI set out to discredit and destroy the BPP by infiltrating the group and setting members against one another. Drugs, egos and disorganization also contributed to the problem. At times, it seemed the Panthers didn't need any help breaking up the band. "Do you think anyone still cares about the Black Panthers?" I was asked last month at a dinner party in Oakland, California, just miles from Merritt College, where students Newton and Seale came up with the party's 10-point program and flipped a coin to see who would be chairman. (Seale won; Newton became minister of defense.) And this was from someone who had produced a documentary about Mumia Abu-Jamal, the former Black Panther on death row for killing a Philadelphia police officer in 1981. Maybe people don't. Most ex-Panthers are in their 70s now and probably not in your Twitter feed.

As Black Lives Matter is doing today, the Panthers responded forcefully to police brutality (with guns instead of cellphones), but they also fed thousands and opened health clinics for the poor. And as indicated by recent police shootings and protests—Tulsa, Oklahoma, and Charlotte, North Carolina, in September and perhaps somewhere else by the time you read this—their mission remains unfulfilled.

"'Black Lives Matter' is a call to action and a response to the virulent anti-black racism that still permeates the American landscape," Seale wrote last year. Yet some have a hard time figuring out what principles underlie the movement and what, specifically, it hopes to achieve. "I'm not sure what your point is in raising all the names of these people who are dead if you don't have a real plan for what to do," says Elaine Brown, chairwoman of the BPP from 1974 to 1977, about Black Lives Matter. "And they don't seem to have a plan. Our plan was revolution. We had an ideology; it was called revolution."

'Barely Escaped a Lynching'

"A toddler named Huey Newton was spirited from Monroe [Louisiana] to Oakland with his sharecropper parents in 1943," Isabel Wilkerson wrote in The Warmth of Other Suns, her award-winning book about the African-American diaspora. "His father had barely escaped a lynching in Louisiana for talking back to his white overseers. Huey Newton would become perhaps the most militant of the disillusioned offspring of the Great Migration."

Billy X. Jennings was Newton's aide in the early 1970s and is now the party's unofficial historian; his website, It's About Time, is a clearinghouse for all things Panther. Jennings's parents were from Anniston, Alabama, where locals torched a Freedom Riders bus in 1961. "First thing we did when we came to California was my dad had to buy my mom a TV," says Jennings. "Every day, we'd watch Walter Cronkite breaking down what's going on, and my mother used to get so mad at Bull Connor and the rest of those racists, she would get up and turn off the TV, boiling mad. She'd look at me and say, 'Boy, don't you never let nobody treat you like that!'"

The Panthers were born at a time when police violence went largely unreported, and political assassinations were as much a staple of the daily news as shootings at schools and malls are today. Small wonder these guys wanted to take up arms. "I was highly influenced by Martin Luther King at first and then later Malcolm X," Seale said in 1988. (He declined to be interviewed by Newsweek; Newton was murdered by a member of a drug-dealing gang in 1989, not far from where he grew up in Oakland.) "Largely, the Black Panther Party came out of a lot of readings." Armed with guns and law books, Seale and Newton began "police patrols": They and other members of their nascent party would drive around Oakland's black neighborhoods and pull over to observe cops who had stopped citizens, often without cause. (Both Keith Scott in Charlotte and Terence Crutcher in Tulsa were shot by police who stopped them and believed them to be armed.) "The guns [were] loaded," Seale recalled. "They're not pointing at anyone because we also know [under] California Penal Code [that] constitutes assault with a deadly weapon." Their interventions were dramatic and began to win the Panthers respect in the community. "Ultimately, they made a law against us, to stop us from carrying guns," Seale said. "That's how legal we were."

On May 2, 1967, a contingent of about 30 Panthers went to the state Capitol in Sacramento to protest legislation to ban the public display of loaded weapons—a bill inspired by those armed Black Panthers. Governor Ronald Reagan was on the lawn in front of the building, talking to a group of parochial schoolchildren when the Panthers arrived. Reporters quickly abandoned Reagan and the kids to photograph the armed revolutionaries strolling toward the Capitol steps. "Who in the hell are all these niggers with guns?" a security guard asked, and after the Panthers marched into the assembly chamber, their rifles pointed toward the ceiling, some legislators took cover. The group was ordered to leave, and many of the Panthers, including Seale, were arrested for "disturbing the peace."

The sight of those gun-toting black men and women only helped the legislation get passed: The Mulford Act (aka the "Panthers Bill") had the support of Reagan and the National Rifle Association, and California still has some of the strictest open-carry laws in the nation. But the Panthers were never really about the guns; their 10-point program demanded jobs, housing, health care and control over the institutions that affected black people's lives. Though the sight of armed black men in the streets of Oakland was a real conversation starter, guns were not going to awaken people to what the Panthers saw as institutionalized racism, let alone win the revolution.

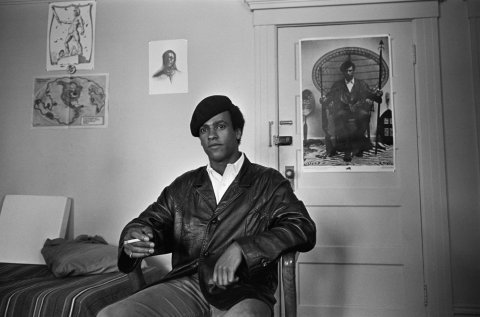

"If we had pooled our guns together from all over the country and were prepared to fight, we would not have won a battle against the LAPD," says Brown. (The Los Angeles police engaged in a four-hour shootout with six Panthers in 1969; though they ultimately surrendered, and no one was killed that day, the news footage of half a dozen men battling 200 cops, not to mention the nation's first SWAT team, made an indelible impression.) And while the defiant image of the group resonated with a lot of young people (a poster of Newton in a rattan throne, a spear in one hand and a rifle in the other, adorned many a dorm room wall), it clearly scared the hell out of the authorities. "If you talk about revolution against the state," says Peniel Joseph, author of Waiting 'til the Midnight Hour: A Narrative History of Black Power in America, "the state responds accordingly!"

In the early hours of October 28, 1967, Newton and another Panther were stopped by Oakland policeman John Frey; Newton produced a law book and, after Frey insulted him and struck him in the face, a gun. Frey was killed in the melee, and a wounded Newton nearly became the BPP's first martyr. Newton was convicted of voluntary manslaughter. "Free Huey" became the movement's rallying cry, and in 1970 his conviction was reversed on appeal. (Another Panther who'd been on the scene took the Fifth when asked if he might have "by chance" shot Frey.) By then, the BPP had grown to over 50 chapters, boasting thousands of new members. And while many of those new recruits came for the guns, they stayed for the ideology.

Jamal Joseph was 15 when he entered a BPP office in Brooklyn, New York, in 1968. Joseph was an honor student who had been radicalized by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. and was eager to join the Black Panthers. "My friends had told me I'd have to prove myself and probably have to kill a white dude, if not a white cop," he recalls. "Jumping up in the meeting, not really listening to someone explaining the 10-point program, I said, 'Choose me, brother! I'm ready to kill a white dude!' The whole room gets quiet. The brother that was running the meeting calls me up front and looks me up and down, real hard. He was sitting at a wooden desk and reaches into the bottom drawer. My heart was pounding, like, Oh my god, he's gonna give me a big-ass gun!' And he hands me a stack of books: The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Soul on Ice by Eldridge Cleaver, The Wretched of the Earth by Franz Fanon, the famous Little Red Book [Q uotations From Chairman Mao Zedong ] we all carried.

"And I said, 'Excuse me, brother, I thought you were going to arm me.' And he said, 'Excuse me, young brother: I just did.'"

America's Scariest Breakfast

Ideas are far more dangerous than guns; sometimes, so are pancakes. The communist ideas Seale and Newton had discovered in college fit with their view of racial oppression in America; they were also anathema to most of "the Greatest Generation" and (not coincidentally) of renewed interest to their kids. (The Panthers made money selling Quotations from Chairman Mao Zedong to University of California, Berkeley, students for a dollar, after buying them for a quarter.) But to reach deep into the black community, the party needed to be more than just articulate and well-read; they needed to provide safety, education, food.

"The germ of the social programs was always in the party's original imagining of itself," says Nelson. In January 1969, the Panthers started serving breakfast for kids at St. Augustine's Church in Oakland at no charge; the Free Breakfast for Children program went national and was soon feeding 10,000 kids a day. The press loved it, and people liked seeing Panthers serving pancakes. Not all people, of course.

The FBI had already infiltrated the BPP, and much of the internal strife that finally tore the party apart was stoked by informants—and obsessively monitored by J. Edgar Hoover, who called the Black Panthers "the greatest threat to the internal security of this country." It was in the early '70s that Cointelpro, the bureau's secret program to disrupt revolutionary groups, was most active. "What Hoover feared about the BPP the most was not the berets and the guns," says Jamal Joseph. "It was the Panther breakfast program. He thought this was the most subversive program in America…. He was right in that it was a formidable organizing tool because we used the breakfast program to point out to kids that not only do you have the right to eat, but what kind of country do you live in that you have to go to school hungry?"

And breakfast was the least radical of the group's demands. Revised in 1972, the 10-point platform says, "We want completely free health care for all Black and oppressed people," and starting around that time the Panthers began pushing for that in their communities. "The Panther encouraged all their social programs, but didn't provide resources to develop them," says Nelson. "They had to figure it out for themselves…. They had to find their own volunteers and doctors, nurses, medical supplies." The idealistic medical personnel they recruited were inspired by the example of the Medical Community for Human Rights, a group of doctors who'd participated in 1964's Freedom Summer. And the DIY clinics that sprang up in storefronts and trailers in cities across the country, where people would come for emergencies or to be screened for sickle cell anemia, were part of a larger trend. The Haight-Ashbury Free Medical Clinic in San Francisco had opened in 1967 to treat residents for crabs and bad acid trips, while the Boston Women's Health Clinic begat the feminist health bible, Our Bodies, Ourselves.

"I think it would be impossible today to do what the Panthers would do, which would be to go to a storefront, take some equipment and some doctors, or people with training, and set up a clinic," says Nelson. You'd need to have the existing health care structure utterly decimated—as it was in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in 2005.

Two days after Katrina ripped through the city, when bodies were still floating in the flooded streets and President George W. Bush was flying overhead, former Black Panther Malik Rahim started the Common Ground Clinic, says Nelson. "When asked, 'How in the world are you going to do this when the city is destroyed?' he'd say, 'We did this when we were Panthers.'"

Chairman Mau-Mau

"History doesn't repeat itself, but it does rhyme." While there's no evidence Mark Twain actually said that, it's the sort of expression historians use to explain similarities and differences between then and now, and groups as diverse as the Panthers, which took root in the ghetto, and Black Lives Matter, born on the internet.

By 1970, the Panthers had achieved celebrity status, and their fundraisers for the Panther 21 (New York members arrested on charges of planning bombings throughout the city) were held in some of Manhattan's swankiest apartments. Tom Wolfe attended one at Leonard Bernstein's home and lampooned the proceedings in the New York magazine article "These Radical Chic Evenings": "'I've never met a Panther,' one of the attendees told Bernstein's wife; 'this is a first for me!'… never dreaming that within forty-eight hours her words will be on the desk of the President of the United States." (Richard Nixon shared Hoover's obsession with the Panthers and the white liberals who supported them.)

Almost 50 years later, members of Black Liver Matter were invited to the White House to meet with President Barack Obama, who later criticized the group for not moving beyond protest. "Once you've highlighted an issue and brought it to people's attention and shined a spotlight, and elected officials or people who are in a position to start bringing about change are ready to sit down with you, then you can't just keep on yelling at them," Obama said.

This was December 2014, while there were people protesting police shootings in large numbers across the country, shutting down roads and malls in the run-up to the holiday season. When one of those in attendance said they felt their voices weren't being heard, Obama said, "You are sitting in the Oval Office, talking to the president of the United States."

"It felt like that meeting was, 'Come and sit down, and let's figure out how we can get back to business as usual,'" says Ashley Yates, a Black Lives Matter activist from Oakland who was there. "I don't know how helpful it was, but it did feel like in that moment we were seen," she says. "But it also felt like Obama was taking that moment to tell us to go slower, something we talked about later. A little bit of both, a little bit of politician double-talk—'It's a long fight, guys, and since it's a long fight, you might want to save your breath.' And we're like, 'We have enough to go hard.'"

Call it another of those rhyming-history moments: President Lyndon B. Johnson said something similar to King during the civil rights struggle, sometimes in that same room.

One obvious difference between then and now is that Obama is our nation's first black president; another is that today's Black Lives Matter movement has less clear goals than ending segregation (such as "dismantling the patriarchal practice that requires mothers to work 'double shifts'" and "embracing and making space for trans brothers and sisters")

"I think just the declaration 'Black lives matter' is everything that the Panthers were about," says Yates. "Just saying that black people are worthy of defense, that black people are worthy." The 31-year-old spokeswoman has history with the BPP. While a member of the Legion of Black Collegians at the University of Missouri, Yates brought Fred Hampton Jr. to speak on campus. Hampton, son of the Chicago BPP leader murdered by Chicago police in 1969, was in his mother's womb at the time of the shooting; today, he is chairman of the Prisoners of Conscience Committee, which bills itself as "a revolutionary organization."

"I don't think we have the analysis as a movement at large that the Panthers did around imperialism, internationalism, international solidarity and what it really means to push against the American empire," Yates says. "My generation and this movement have just started to see that [for us], one of the largest forms of oppression is not Cointelpro; we talk about diversion tactics, divide and conquer, but what we're really trying to raise [is] the tactic of imprisonment as a tactic of oppression." Their issues may not fit easily on a placard, but the image of Michael Brown's body—lying uncovered on the street in Ferguson, Missouri, for hours after he was shot by a white policeman—proved as galvanizing as that of Huey on the throne.

Chicago Police Killed the 'Black Messiah'

The idea of "community" has morphed since the Panthers' time and even Obama's days as a community organizer in Chicago. "I think Black Lives Matter is absolutely connected to the larger civil rights–Black Power period," says Peniel Joseph. "It's rooted in the same fight, but things have changed because the black community has become much more stratified, much more geographically separated than it was 50 years ago."

Born in the wake of the Trayvon Martin shooting, Black Lives Matter went from a hashtag to a national movement in the summer of 2014 with the sometimes violent protests that followed the shooting of Brown. Social media allows the movement and its most recognizable figures to remain in touch in ways the Panthers could hardly have imagined. Black Lives Matter spokesman DeRay Mckesson, for instance, posted a video on Periscope of himself getting arrested in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, following the police shooting of Philandro Castile, in July 2016.

"All we had were transistor radios and walkie-talkies, mimeograph machines," says Jennings of the Panthers' early days. "It took until 1994 and Rodney King getting his ass kicked for people to believe that there was really police brutality going on. And look at all the thousands of people who took ass-kickings way before that time!" (Forty-six years after it was recorded, Gil Scott-Heron's "The Revolution Will Not Be Televised" remains prophetic, if somewhat ironic: "There will be no pictures of pigs shooting down brothers on the instant replay.")

Though the methods for distributing cellphone, dashboard and body cam videos have made the outrage more instantaneous (and incontrovertible), some ex-Panthers feel there's no substitute for organizing. "It's almost like we have too much information," says Jamal Joseph. "People spend so much time on their devices, reading on their laptops, that we're not getting in the same room the way we did." (Or as Yates says, "It's a lot easier to establish yourself as an expert who has done things in the movement when you're sitting at home tweeting." )

Joseph was one of the Panther 21 (who were acquitted of all 156 charges in 1971) and later, the Black Liberation Army, which ambushed police in the '70s. He served time in Leavenworth for his involvement in the 1981 Brink's robbery in which two security guards were killed and earned two college degrees while inside. Today, he is a professor at Columbia University, "of which I used to say, 'Let's burn this damn place down!'"

He is often called upon to speak to young black activists. "When I talk about it, I get a little dismayed," he says. "I give a pretty good speech, a pretty good pep talk. They take it to heart, and then they leave and get right back on their news feed, you know what I mean? 'Panthers were cool,' they tweet, and then go back to what they were doing."

Political process is less stimulating than protest, but it's where many revolutionaries end up after trying to change the system from without. By the early '70s, the Panthers were shifting from agitating to campaigning. Seale ran for mayor of Oakland in 1972 and lost in a runoff; Brown ran unsuccessfully for City Council twice before managing the campaign of Lionel Wilson, who became Oakland's first black mayor in 1977. Black Lives Matter's Mckesson, currently the interim chief of human capital for Baltimore City Public Schools, ran for mayor of that city this year. "An outside-only strategy is not a strategy to win," he says. "The Black Panthers serve as an important model for a way to organize and have inspired activists and organizers in continuing to develop new ways of organizing as tools change and the context changes."

The Panthers will have a chance to inspire more people in Oakland this month; the Oakland Museum is opening an exhibition called "All Power to the People: Black Panthers at 50," and there will be reunions of both party members and people from affiliated groups, such as the Brown Berets, the Young Lords and a largely forgotten white group from Chicago called the Young Patriots, who had met with Fred Hampton, the charismatic leader Hoover privately feared was the "black messiah" who would unite the disparate revolutionary groups of the '60s.

"They organized the same way the BPP did, around tenants' rights," recalls Brown, even though they were not the most natural of allies. "Some of them would have jackets with a Confederate flag sewed on them, and they were working with the BPP to the point where, when Fred Hampton was killed, many of them were calling him Chairman Fred. I'm talking about tobacco-chewing, teeth-missing, no-shoe-wearing, call me 'nigger' [guys]—that's what I'm talking about. I'm not talking about the SDS [Students for a Democratic Society] white people who went to school in Berkeley. I'm talking about some serious white people."

Brown believes that if the Young Patriots had survived, "these people would not be voting for Donald Trump." But maybe revolutionary groups are built to fall apart. "The goal of the BPP was not to have every member of the black community become a Panther," says Joseph. "The goal of the party was to show people the possibility of struggle, the possibility of fighting for your freedom.

"We wanted to make ourselves obsolete."