Want to bring down Donald Trump?

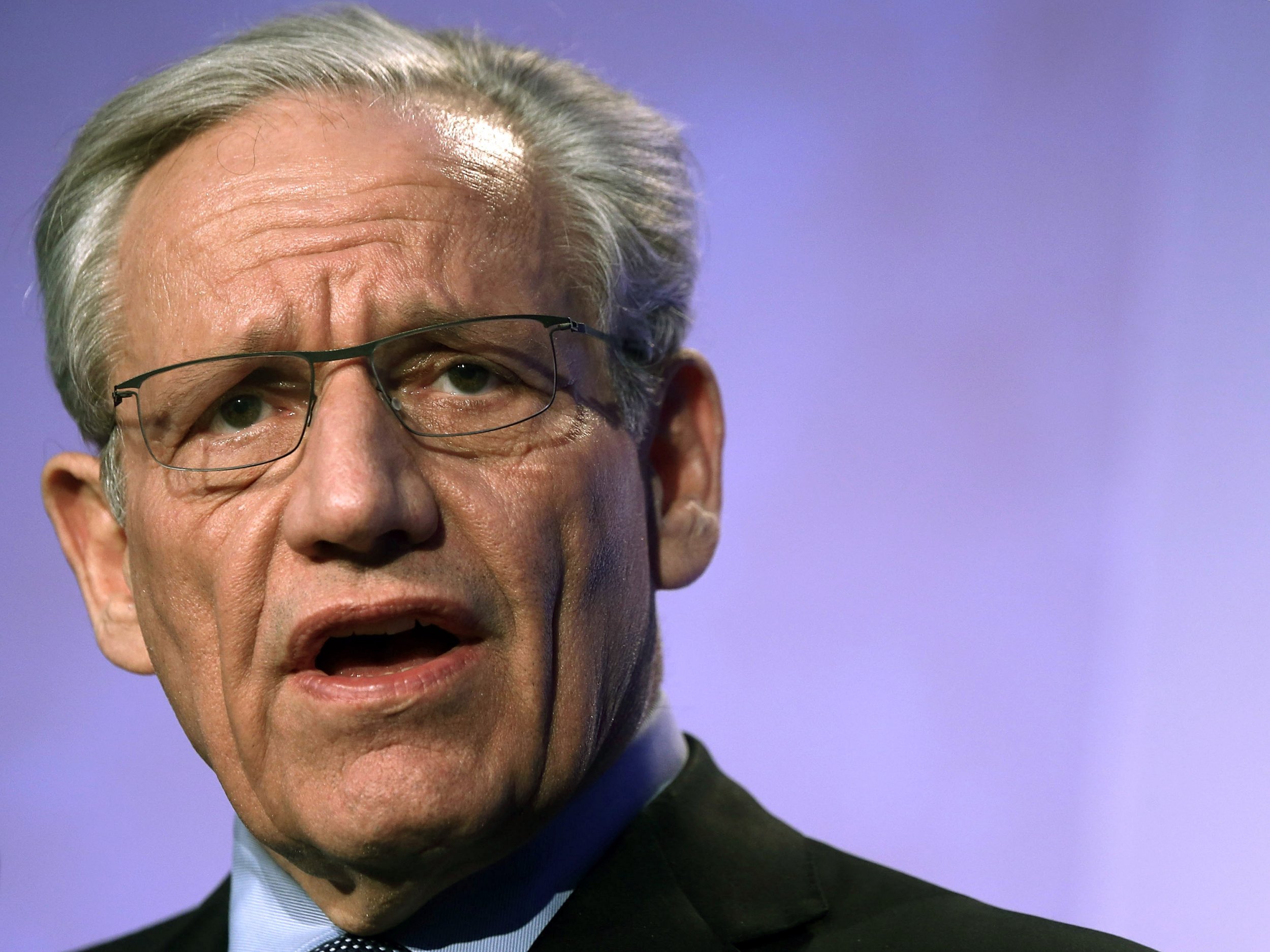

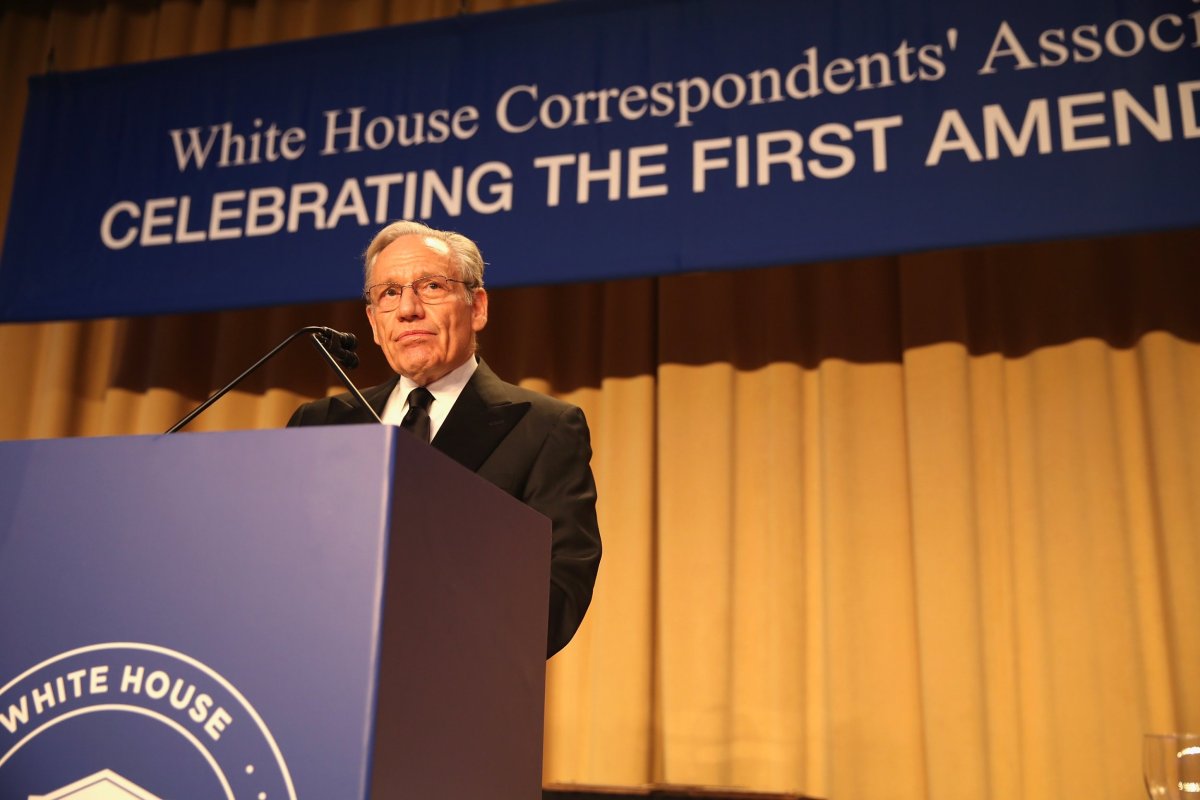

Don't count on Robert Mueller. Forget Congress. Learn to do investigative journalism. And you might as well study with one of the only living people who really did help oust a president: Bob Woodward.

He's best known for his historic work covering the Watergate revelations for The Washington Post with reporting partner Carl Bernstein. Woodward, still a Post journalist 45 years later, is now spilling his secrets by teaching a MasterClass (an online MasterClass.com workshop) on reporting. The timing couldn't be better: Donald Trump's various scandals, coupled with movies like Spotlight and The Post, have awakened a national interest in investigative journalism, and he is historically well-suited to offer insight.

But Woodward would chasten you for approaching the work with a political agenda. "It's important to get your personal politics out," the 74-year-old journalist says. "The emotion should be directed at doing more work."

In one MasterClass lesson, Woodward has this advice for journalists conducting interviews: "Shut up…and just listen." I tried. We talked about journalism, Trump, Richard Nixon and a lot more.

The work that you've done is remarkably difficult and laborious. Is it possible to teach someone to be an investigative reporter?

I've done it now at The Washington Post since 1971—that's 47 years. And [I gained] lots of experience from Watergate. I tried to make the point in the class that technique is so important. Patience is important. It's very much against the impatience and speed of the internet reporting world. One of the great problems is that secret government gets more and more secret. If you're in a hurry or try to do interviews via the internet or email—or even the telephone—you're not showing up to meet people and trying to build relationships of trust.

Do you have any faith that investigative journalism can survive the shifts that have occurred in journalism?

I think it is surviving! My own newspaper, the Post, New York Times, Wall Street Journal, some of the networks—CNN, NBC—have done some very important stories on the Russia investigation and Trump.

Smaller papers have been facing tough times, though. Are you optimistic about the future of journalism despite all the frightening trends?

Some of the trends are frightening. But I think people still want good information. I'll go back to the lockdown, the secrecy. There are inappropriate questions to ask people, according to the White House press secretary. That is an environment that requires lots of patience and willingness to spend time against the problem. Talk to 20 people. 40 people. Not just two or six. The key to unlocking what's secret is a lot of concentrated reporting.

You've described the Trump presidency as being a "test" for the news media. Do you think the media is failing the test?

First of all, journalists can always do better. Myself at the top of the list. I don't think journalism is failing at all in the Trump era. But we have a lot of work to do. A number of reporters have at times become emotionally unhinged about it all, one way or the other. Look at MSNBC or Fox News, and you will see those continually either denigrating Trump or praising him. I think the answer is in the middle, and in this class I talk about how it's important to get your personal politics out. It's destructive to become too politicized. The emotion should be directed at doing more work, not some feeling or personal conclusion.

What's your biggest regret from your own career?

Janet Cooke made up a story that won a Pulitzer Prize, and I was one of her editors. I should have spotted it. About an alleged 8-year-old who did not exist. If I'd been more aggressive, I would have discovered that he didn't exist. I personally was not aggressive enough on looking at the evidence of weapons of mass destruction before the Iraq War. I wrote stories saying there's no smoking gun evidence, and I should have realized if you don't have smoking gun evidence, you don't have hard evidence. If you don't have hard evidence, you really don't have it.

Do you think the comparisons constantly drawn between Trump and Nixon are accurate?

Well, we're going to see. Nixon resigned, and we learned from thousands of hours of his secret tape recordings the depth and level of his criminality. The piston driving him and his politics was hate. We don't have that kind of evidence in the Trump case.

Do you think this will end how the Nixon presidency ended?

No one who works on Trump as a reporter would say "X is gonna happen" or "Y is gonna happen." You never know in Trump world. I think it's possible. He has the authority to make sure that the special counsel is fired or out of office.

There has been an enormous amount of renewed interest in Watergate over the past year.

People look back at old scandals, and I think that's reasonable. [During Watergate], there was a clear crime. A burglary. No one said, "Oh, to look into that is a witch hunt." Nixon didn't like it. But it was clearly a crime. There were secret tapes that showed the nature of the criminality and the extent of it. That kind of evidence—it certainly has not yet emerged in the Trump investigations.

How do you think Nixon would have used Twitter?

[Laughs.] Easier to describe the creation of the universe. He probably wouldn't have used Twitter! He would have delegated it. In a sense, his secret tapes are his tweets. And they're appalling in the revelation of abusive power and criminality.

And the prejudice. The anti-Semitism is pretty remarkable.

Yes, it is. When Nixon resigned, he gave a speech. You're too young, I'm sure. How old are you?

I'm 27.

[Chuckles quietly to himself.] OK, this is back in '74 when he resigned. He called his staff and friends and Cabinet to the East Room and gave a speech. It was unscripted. He was sweating. He talked about his mother, his father. At the end, he waved his hand like, "This is why I called you together." He said: "Always remember, others may hate you. But those who hate you don't win unless you hate them, and then you destroy yourself." Think about that. He identified hate as the poison that destroyed him in his administration. And it did.

That's a really telling quote.

I remember sitting there at the time—I was 31—and just going, "Wow." He got it! The diagnosis was exactly right. It was hate! And it destroyed him.

I don't think President Trump has that level of self-awareness.

Well, that's an interesting question. I'm doing a book on Trump now. I'm going to stick to my reporting, which is still ongoing.

Related: Jodi Kantor, the reporter who helped bring down Harvey Weinstein

Have you seen the movies Spotlight and The Post? What do you think of the way they depict investigative journalism?

Spotlight is a great movie about that process. The nitty gritty. You've got to go into the night. It is a longtime effort to win trust with people. [Spotlight producer] Steve Golin bought and is gonna make a movie of my last book, The Last of the President's Men. The Post I thought was also excellent. I thought Meryl Streep played Katharine Graham [Woodward's onetime publisher] superbly. As did Tom Hanks as Ben Bradlee [the editor-in-chief who pushed to publish Woodward and Bernstein on Watergate].

Were you fond of the movie that was made about Mark Felt last year?

I don't think it worked.

Why not?

Oh boy. It had too many characters from the FBI that you couldn't differentiate. It had the subhed The Man Who Brought Down the White House. He was a source—and helpful. But he was not the one who brought down the White House. We—Carl and I—were not the ones to bring down the White House. It was a series of events in the press and investigations from Congress and the special prosecutor and the Supreme Court ordering Nixon to turn over his tapes.

Some of the biggest stories in journalism lately have been the result of the Harvey Weinstein revelations. Publications have been devoting major investigative resources to covering sexual misconduct scandals.

I think it's absolutely appropriate. They nailed it. They nailed the Harvey Weinstein case. There were just so many examples.

Why did it take so long for that to come out?

Jeff Bezos once asked me, "Could we have learned what Nixon was about—this hate-driven man—could we have learned before he became president?" I said, I think we could have done better. But I don't think we could have gotten to the bottom of who he was. We now know this anger and hate was standard for Nixon. Why did it take so long? It's a hard process. You need good sources. What The New York Times and New Yorker did with Weinstein, I remember reading those stories and saying to myself, "This is a revolution of sorts." But like all revolutions, it's the old way. It's the technique of building those sources.

We've seen other reported stories that haven't received the same level of journalistic technique. Did you read about the Aziz Ansari scandal?

About who?

Aziz Ansari, the comedian?

Just a little bit. But Harvey Weinstein was the producer of producers. He was the No. 1 person. You could read that story and say, "Aha!" You could see that this was not an isolated case, as we now know.

Have you read about the current turmoil that Newsweek has been embroiled in?

I have a little bit. I don't have any facts about it, but it sounds like some people are really upset and there seem to be grounds for being really upset. What do you think?

Well, it's disturbing. The short version is that our owners' finances are under DA investigation. Our own journalists began reporting on the story. Some employees were subsequently fired for reporting on our company.

If that's all true, that's appalling. That's a form of corporate leverage that is the height of corruption, in my view.

It also seems destructive to the separation of the journalism side and the business side.

For decades, The Washington Post owned Newsweek. I know how Katharine Graham ran it. And how the editors ran it. It was a superb, tough, independent organization. Obviously, it's lost some of that. It's too bad. When people look back, you would be a casualty of the internet era. Is that correct?

Well, it's hard to sell a print magazine in this era. One concern of many journalists is that media companies that are flourishing are ones that have the backing of a billionaire, like Jeff Bezos.

Yeah, yeah.

Do you find it concerning that so many major journalistic organizations rely on billionaires for funding?

The Post is supposedly making money now. Bezos, who owns it personally, not through Amazon—he's put lots of money into it, hired many more reporters. And in the great tradition of Katharine Graham, [Bezos is] what I call "mind on, hands off." He does not put his hands on the product at all and say, "This is what editorial should be." He leaves that up to the professionals. The people at the Post who I know and still work with would not tolerate that.

The Post has gotten many scoops in the Trump era. What is the secret to its recent success?

Hard work. Persistence. You have to try to talk to everyone who might know about something. That takes weeks, months. Back in the Watergate era, Carl and I could work for weeks on a story before it was published. We would be interrogated by editors. They would say, "We need more. Get better sources. Get more concrete information." The culture of patience has once again arrived in the Washington Post newsroom.

Are there any other veterans at the Post who were there when you were reporting on Watergate?

You mean, am I the senior person still there?

Well, that's another way to ask the question.

Yes, it is. I don't know. I'm sure there are people who go way back.

Do you plan to continue reporting much longer?

Yes. I'm doing this book on Trump. I've done [reporting] for so many decades, I kind of expect to do it as long as I can still type. Being a reporter is the greatest job in the country. You get to make momentary entries into people's lives when they're interesting. And then get out when they cease to be interesting.

Are you and Carl Bernstein still close?

Yes! We are. In fact, we have to do a CNN show tonight. I'll be seeing him tonight.

Do you two hang out socially as well?

We do, occasionally.

What do you do to wind down when you're not working?

You mean with Carl? Well, we're both married and we take our wives to dinner. Or he and Christine, his wife, will visit here. I teach a journalism seminar at Yale. Once a week. So it's, at this point, a very work-filled life.

How would you like history to remember you?

I'm not heading to the grave, to my knowledge. So I don't really know. That's for others.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.