During its six-year insurgency in northeastern Nigeria, Boko Haram has killed thousands of people and displaced millions in its bid to realize its fundamentalist vision of an Islamic caliphate. In that quest, it has persecuted Nigeria's Christian population and sought to exterminate Christian clerics, including Hassan John, an Anglican pastor from Jos, central Nigeria.

John, 52, is used to living with the perpetual threat of Boko Haram. "Every Christian cleric anywhere has the same bounty on his head," says John, who is currently studying at the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics in the U.K. "If you are a pastor or a priest, from Jos all the way to Maiduguri, you do have a bounty on your head." The price of John's life, according to the militant group, is 150,000 naira ($754)—slightly more than the going rate for an iPhone 6s in Nigeria. The bounty, however, has not stopped him from reaching out to Nigeria's Muslim community in order to build bridges burned down by Boko Haram's violent actions.

The Anglican pastor is currently studying in Oxford, but will return to his hometown of Jos in July, where he works with Muslim communities. Jos, the capital of Plateau state, lies in the central belt of the West African country. Nigeria is roughly 50 percent Muslim and 40 percent Christian, but the vast majority of Muslims are concentrated in the north—the epicenter of Boko Haram's insurgency—while Christians tend to live in southern states. Jos, as John describes it, lies on "the fault line between the two forces."

John has been working for the Anglican Diocese of Jos for roughly six years, the same timeframe in which Boko Haram has wreaked havoc in Nigeria. His main cause is rebuilding Christian-Muslim relations in Jos, which were heavily damaged by a series of interreligious riots in 2001, 2008 and 2010. In the most recent round of rioting, as many as 500 people —mainly Christians—were slaughtered in March 2010 in Dogo Na Hauwa, a village near Jos, in reprisal killings for deadly massacres of Muslims in January 2010. These tensions came just months before Boko Haram detonated a series of bombs in Jos and Maiduguri that killed at least 38 people, an attack the militants said served as vengeance for the deaths of Muslims in the interreligious violence.

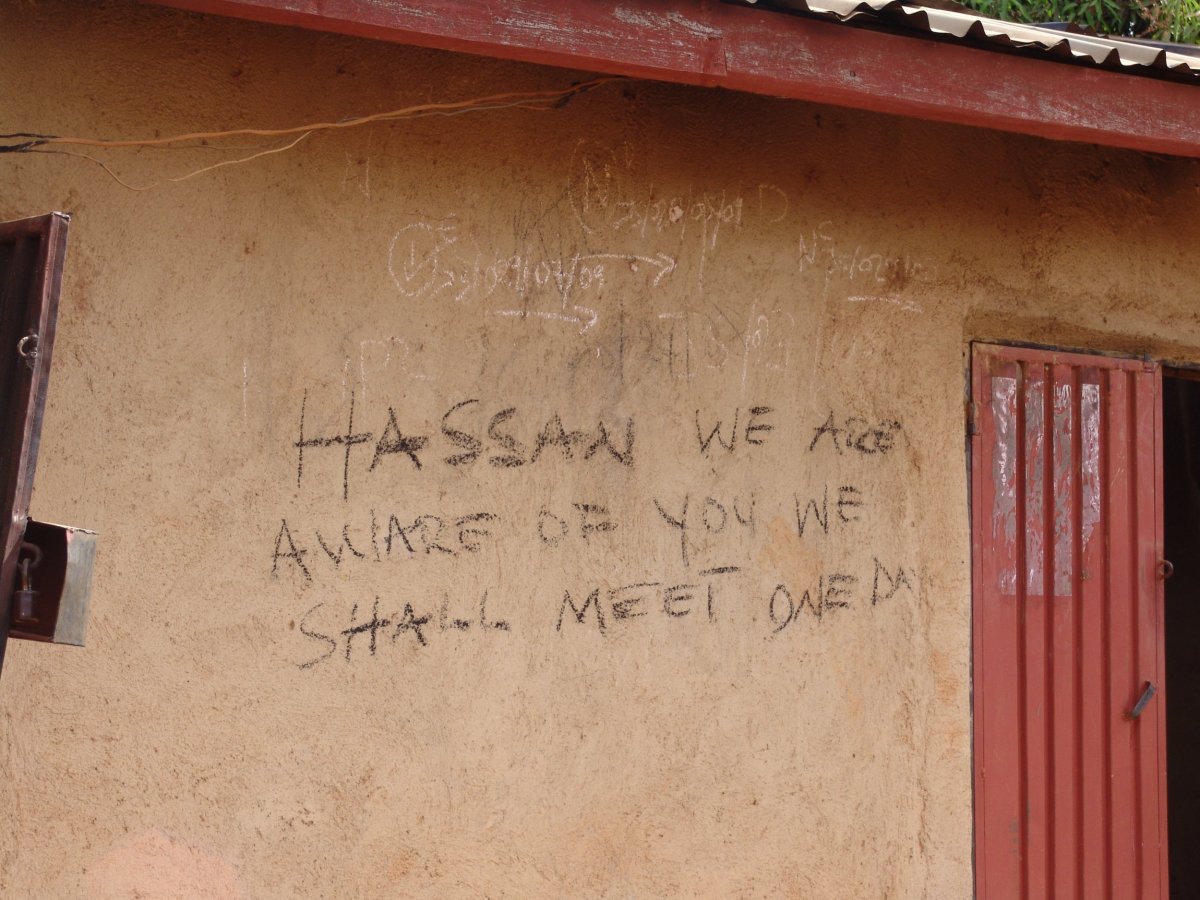

John has been documenting clashes between Christians and Muslims, as well as the results of Boko Haram attacks, in and around Jos. A former journalist with a government-run Nigerian broadcaster, John estimates he has visited the sites of 80 attacks in the past five years. His work in the media, coupled with his positive agenda for Christian-Muslim relations—pairing Muslim widows with Christian mentors to learn handicraft and trade skills—has made him a target for Boko Haram. John recalls one occasion, in April 2010, when he visited the village of Byei, south of Jos, which had just been subject to a suspected Boko Haram attack. The pastor discovered graffiti, which he presumes was left by the militants, warning him that he was a marked man: 'Hassan we are aware of you. We shall meet one day.'

"The first time I saw that I was terrified. For months, if I drove to work on this street [where the graffiti was], I didn't take the same street coming back, I took a different route," says John. He also says he has been subject to anonymous, threatening phone calls, and has even been shot at in the street, both by Nigerian soldiers and unidentified militants. "You really don't know whether you will be next, at any time."

Despite his fears, and the growing nature of the threat from Boko Haram, which is reportedly expanding into other West African countries, John says he has not been discouraged from his work. "I think I have a responsibility to make sure that things work out between the Christian and Muslim communities," he says. "Boko Haram is a factor and we can't deny that, [but] the poison that goes into the Christian and Muslim communities is something that we have to find a cure for. It can't go on forever."

The defining moment of Boko Haram's insurgency came in April 2014, when 276 schoolgirls were kidnapped from their boarding school in Chibok, in the northern state of Borno. Most of the girls remain missing, despite an international Bring Back Our Girls campaign aimed at finding and liberating the girls. John, who visited Chibok in the weeks after the attack, does not hold out much hope of the girls being found alive and says they may have been sold into slavery or married off to Boko Haram fighters, as reportedly threatened by the group's leader, Abubakar Shekau.

"At this stage, I do not see the possibility of the girls being returned. I do not think Boko Haram would have kept them...as a group for all this time. They'd have been too much of a burden," says John.

The Nigerian military has stepped up its campaign against Boko Haram since President Muhammadu Buhari came to power in March. Buhari has pledged that all Nigerian territory currently under the group's control will be liberated by the end of December. Nigeria is also the leader of the Multi-National Joint Task Force , an 8,700-strong military combining Nigerian troops with those of its neighbors Chad, Niger, Cameroon and Benin. In the face of this pressure, Boko Haram has increasingly resorted to guerilla-style attacks, using suicide bombers to sow fear and havoc. A recent suspected Boko Haram attack, on a Chadian island in Lake Chad on Saturday, killed around 30 people as three suicide bombers detonated their devices.

In the unlikely event that the Nigerian army are likely to quash Boko Haram completely by the end of the year, the effects of the insurgency will remain devastating. The militants have slaughtered some 17,000 people since 2009 and displaced around 2.5 million others, according to AFP. Children have been scarred after having the group's violent ideology forced upon them and families have been broken; in the case of the Chibok girls alone, though 57 have returned, hundreds of mothers remain separated from their children.

Despite the group's horrendous—and ongoing—legacy, John says he is compelled to work for reconciliation and even forgives the fighters responsible for the destruction. "As a pastor, of course [I feel] forgiveness towards them [Boko Haram]. I know they strongly believe they are doing things in the name of Allah...but clearly you know that is a distortion."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Conor is a staff writer for Newsweek covering Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, security and conflict.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.