Closing out the 15th edition of New York's Tribeca Film Festival was the world premiere of the bomb, which is not so much a film as it is an experience. Four showings were held in Midtown Manhattan's Gotham Hall over the weekend, inside of which eight screens were mounted side-to-side around the circumference of the interior. For 55 minutes, viewers were bombarded from every angle with an impressionistic array of images, text and video footage that provided a stirring look into the origins, horrors and present-day reality of nuclear weapons. In the center of the circular performance space, four-piece band The Acid performed an ominous, droning soundtrack heavy on electronic effects and ambient noise. It was as immersive as it gets.

One of those in attendance for Sunday night's later showing was filmmaker Richard Linklater, no stranger to experimentation himself. After the screening, he told Newsweek that for people under 35, the film is a way into understanding just how imminent the nuclear threat was during the Cold War, while at the same time providing a reminder for everyone that nuclear weapons are still a very real threat that is largely beyond our control. "People have been lulled into thinking it's a thing of the past," he said.

As for the experience of the bomb itself? "Intense," Linklater said. "Amazing."

But of everyone in Gotham Hall Sunday night, Linklater may have learned the least about nuclear weapons from the bomb. He'd already read Eric Schlosser's Command and Control, the book about nuclear weapons and the "illusion of safety" that inspired the film, which Schlosser created with artist and filmmaker Smriti Keshari. Along with director Kevin Ford, the duo constructed a multimedia experience that transports viewers into a reality that's different from the one shown to us through popular media, which suggests that the nuclear threat ended with the Cold War.

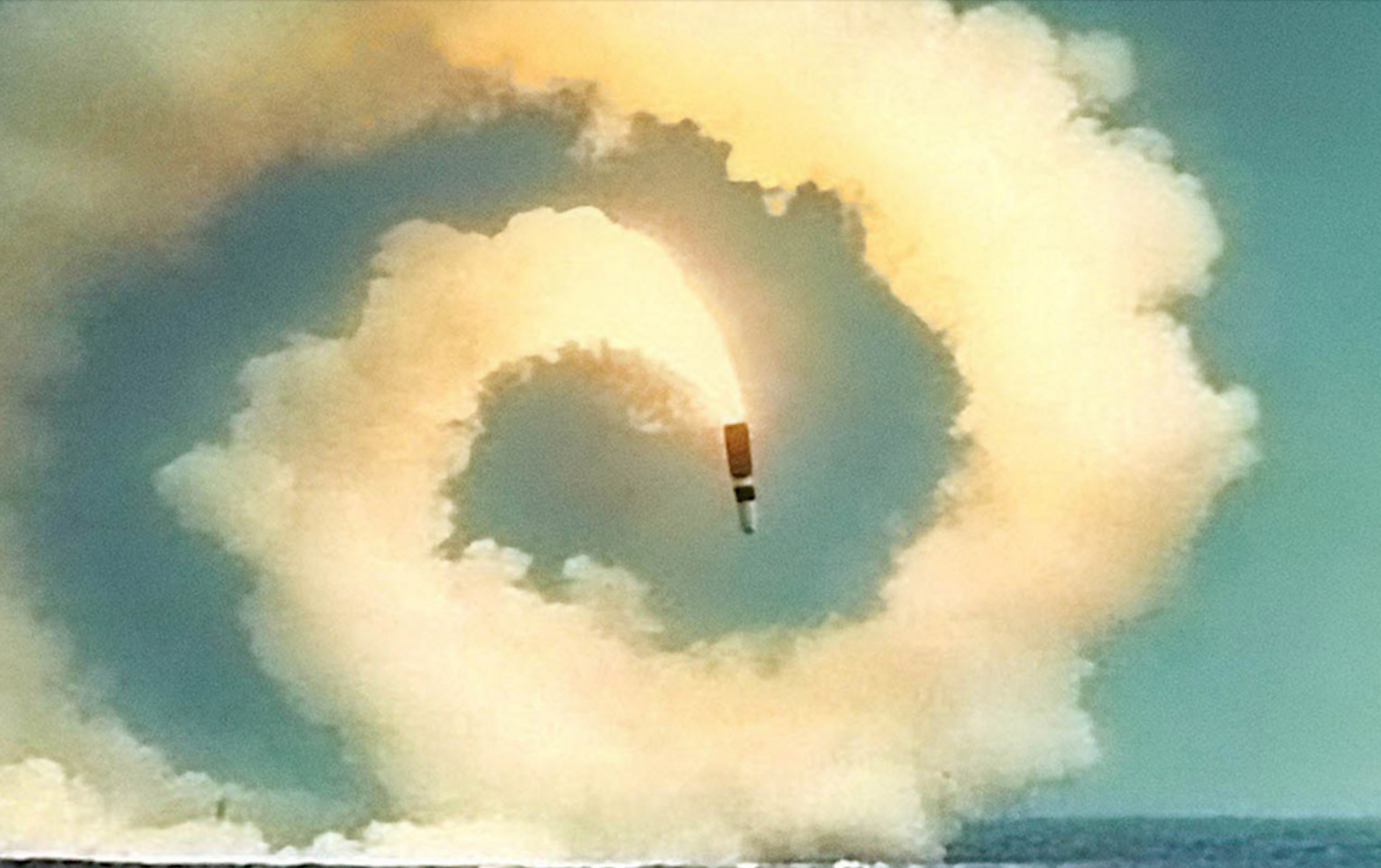

Spending close to an hour inside the world of the bomb gives viewers a uniquely visceral sense of the sheer destructive power of nuclear weapons, which is incomprehensible the same way the power of a natural disaster is incomprehensible until you see it first-hand, or the strength of a bear is incomprehensible until one is ripping you apart. We watch mushroom clouds unfurling in slow-motion, testing footage of trees being ripped from their roots and buildings destroyed, and animals cruelly being stuffed into metal containers so their responses to a nuclear blast can be registered. Rows upon rows of caged pigs, goats and dogs succumbed to the same force that strips paint off the sides of barns. The history of the nuclear program that the bomb forces us to confront is both sordid and gut-wrenching.

Though the power of nuclear weapons was tested throughout the 20th century, it has only been exercised in reality once. A look inside the Manhattan Project's inner workings, soundtracked by the live band playing up-tempo music meant to suggest American innovation and triumph, is followed by a somber, black-and-white collage of images of Japanese families ravished by the bomb's after-effects. It is the only section of the film with no musical accompaniment, and probably its most powerful.

The live music deepened many of the bomb's most haunting moments, but it also caused a few people to dance. Dancing to live electronic music is natural, I guess, but it felt odd considering the horrific nuclear carnage surrounding the people who couldn't help but get their groove on. Unsettling as this may have been, it was part of the dilemma—or the fun—of the bomb experience, which is that no one really knew what to do with themselves. The audience needed to be instructed to stand up and move around instead of remaining seated. Once the film started, no one knew if they were allowed to take pictures or videos (it was a film screening, after all), but as a few phones were unsheathed many more followed, and by the end of the screening everyone had taken at least a few pictures or videos.

The inherent strangeness of the experience—this not knowing what to do with oneself—made viewers vulnerable, which in turn made them more susceptible to the bomb's message. Even when all eight screens were rolling the same footage, the tendency was to dart around, looking for the next thing. But in the case of the bomb, the "next thing" was just more carnage, more explosions and more chilling reminders of the threat nuclear weapons pose. For those of us with short attention spans, there was no escape; we were trapped in the world the filmmakers created and force-fed the harsh reality of what's typically so easy to ignore.

There are more than 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world today, and as the subtitle of Schlosser's book notes, safety is only an illusion. Ultimately, we are at the mercy of our own devastating technology. We have created a monster that cannot be controlled.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ryan Bort is a staff writer covering culture for Newsweek. Previously, he was a freelance writer and editor, and his ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.