This article first appeared on Reason.com.

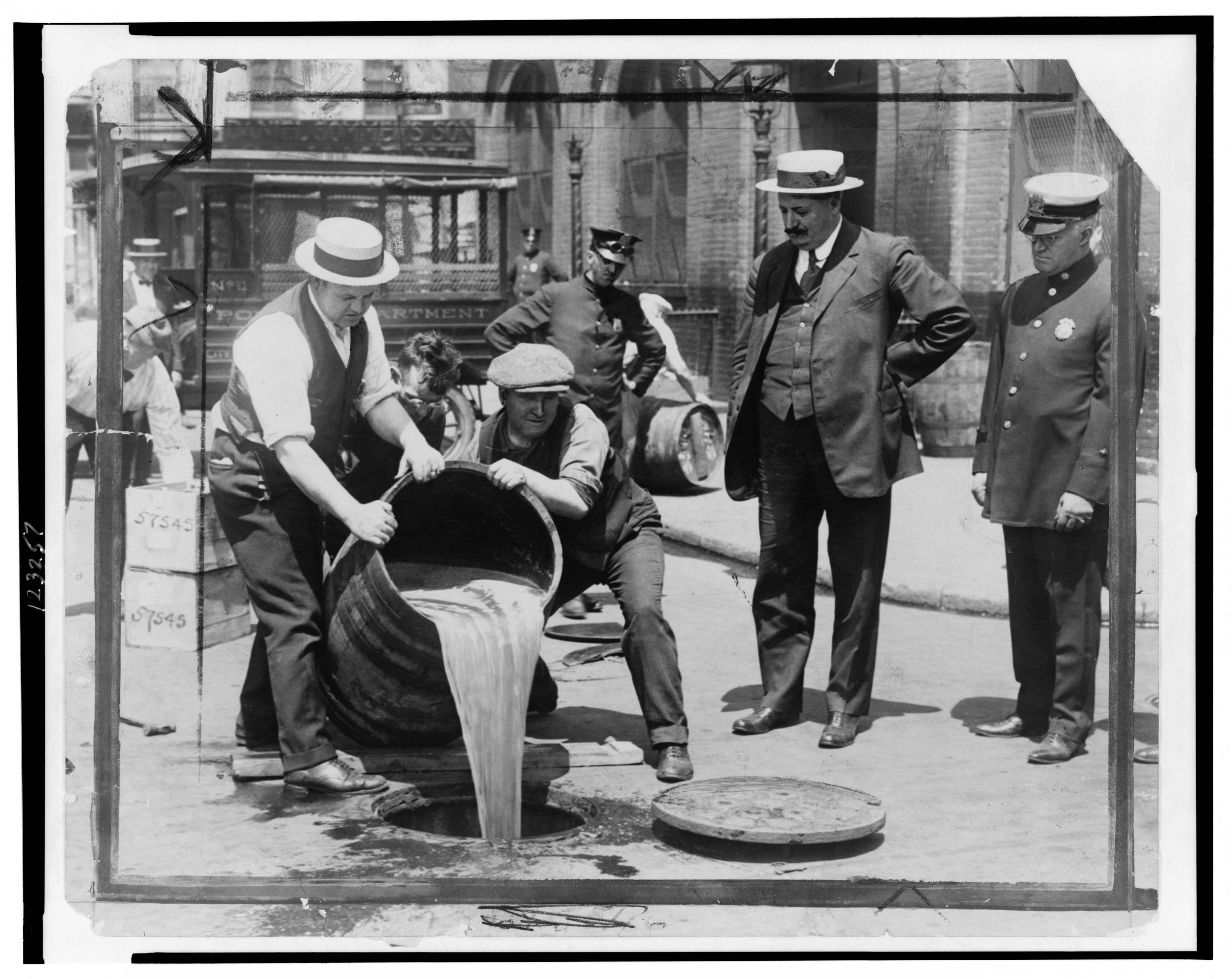

When Prohibition ended in 1933, my great-grandfather, Giuseppe Marano, thought his money-making glory days were over. Having made a good living selling alcoholic beverages to willing buyers at a time when that business was illegal across the country, he and his cohorts certainly viewed the passage of the 21st Amendment as the conclusion of a very profitable era.

Except that it really wasn't. Politicians may have formally dumped the national ban on booze, but in many places they've imposed enough foolish restrictions to keep bootlegging a going concern.

On the first day of this year, it became a class 4 felony in Illinois—up from a business offense carrying a fine—to import 45 liters of liquor or more into the state without a license. The same minimum one-year prison sentence applies to bringing in more than 108 liters of wine or 118 liters of beer without government paperwork.

The law passed as a nudge-and-wink scheme between politicians who resent the loss of tax revenue when beverages are brought across the state line, and local liquor distributors who bristle when out-of-state competitors elbow in on their action.

"Many out-of-state businesses are not compliant with Illinois tax laws, which undercuts Illinois businesses, depriving our state of money that could be going toward improving our schools, roads and social services," Karin Lijana Matura, executive director of Wine and Spirits Distributors of Illinois, an industry trade group, told WQAD, a local TV news station.

The legislation came in response to a thriving illegal cross-border trade as Illinois residents place orders with businesses—many in Indiana—for liquor, wine and beer that is unavailable or just extremely pricey through their state's tightly regulated and protected cartel.

"Alcohol is much more expensive in Illinois than it is in Indiana," reported a Chicago ABC affiliate in 2015. "And it is even pricier in Cook County, where the tax rate on liquor is more than five times higher than it is in the Hoosier State." The result is that "a six-bottle case of vodka that costs $167 in Indiana costs $226 in Illinois and is $18 more than that in Cook County."

Indeed, Illinois taxed distilled spirits at $8.55 per gallon, compared to the $2.68 imposed by Indiana, according to the Tax Foundation. Taxes are also lower in neighboring Missouri and Wisconsin. The Illinois Policy Institute notes that Cook County adds another $2.50 per gallon to the price of a bottle of cheer, and Chicago tags on an extra $2.68 per gallon.

Wine is taxed at $1.39 per gallon, a tad more than the 25 cent rate in Wisconsin. Beer isn't leaned on quite so heavily by the tax man, but Illinois still imposes a higher rate than most of its neighbors at 23 cents per gallon, compared to 12 cents in Indiana, and 6 cents in Missouri and Wisconsin.

And that's assuming you can even find the beverage of your choice to have an opportunity to balk at the price. Chicago "is one of the last contested territories for the nation's two beer giants…which wage a proxy war through licensed distributors" and squeeze out small competitors, Crain's Chicago Business pointed out a few years ago. Federal and state law makes it difficult for small players to bypass established distributors.

So opposition to the new Illinois law found fertile ground among consumers with tastes that couldn't be satisfied locally, "particularly from residents who purchased hard-to-find wine from out-of-state retailers," according to the Chicago Tribune .

"Other states allow out-of-state retailers to obtain a direct shipping license, providing both oversight and valuable tax revenue. We think this is the right approach for Illinois—creating competition, consumer choice, and revenue to help balance our state's budget," their petition said.

All they wanted was a chance to legally place online orders with businesses that carry their drinks of choice, and have the goods shipped to their homes. But they lost, and the tax man and distribution cartel got their pet bill signed into law.

It's not as if Illinois officials are alone in favoring tax revenues and established local businesses over the value of leaving people free to make their own choices.

This year, Michigan adopted a law allowing state retailers to ship wine directly to customers—but barring businesses based outside the state from serving the same market. That's a direct blow not just to retailers who don't have local politicians in their pockets, but also to consumers who want to take advantage of the boom in online vendors and wine clubs of recent years.

And the motivation is no mystery.

"We applaud the House for approving this legislation, which will provide the state with additional tools to crack down on illegal wine shipments into our state," the president of the Michigan Beer & Wine Wholesalers Association crowed.

"It sounds like it's going to shut down some of these mail-order wine clubs, which if those people can't get their wine through those streams anymore, they'll have to come to places like this," the general manager of a Traverse City, Michigan, retail operation told 9&10 News, a local TV station.

Not surprisingly, Michigan has generally higher taxes— $11.94 more per gallon of distilled spirits, 51 cents more per gallon of wine and 20 cents more per gallon of beer—than its neighbors.

The state also imposes an alcohol regulatory regime that the Mackinac Center for Public Policy calls "problematic, because it is designed to unjustly enrich a few beer and wine wholesalers at the expense of consumers everywhere. Indeed, parts of the state liquor code read as if it were written specifically for the benefit of wholesaler business interests."

With high prices essentially mandated by law, Michigan has long enjoyed a healthy, if officially unsanctioned, cross-border trade in alcoholic beverages.

"Conservatively, illegal importation of alcohol into Michigan strips the State of at least $14 million each year," the Michigan Liquor Control Commission estimated in 2007. It fingered Indiana and Wisconsin as major sources of smuggled alcohol—both states, it should be noted, have lower tax rates on all sorts of adult beverages.

Foreshadowing Illinois' transformation of a business offense into a felony a decade later, the Michigan report recommended increased enforcement and penalties as the response to state residents seeking to avoid repeated muggings by government officials and their cronies.

Why correct your own foolish errors when you can lash out at people for responding rationally and predictably to the incentives that you've created?

Giuseppe Marano had his day. But if he were still around, he would recognize a glorious business opportunity when he saw it in the legal, but heavily taxed and regulated, modern booze market.

But it's not like that market is going unserved. My great-grandfather may be gone, but there are plenty of modern bootleggers profiting from the opportunities that politicians have handed them.

Reason.com Contributing Editor J.D. Tuccille writes from Arizona.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.