Research into dyslexia has led to an unexpected breakthrough in security and identity verification with biometric "brainprints" that could one day replace fingerprints and passwords.

Sarah Laszlo, a cognitive neuroscientist at Binghamton University, was working on a method to measure children's brain activity while they read to predict, on a child-by-child basis, who might develop reading problems in the future.

Laszlo's brain readings were spotted by one of her colleagues, bioengineer Zhanpeng Jin, who suggested the research could be taken in a different direction.

"We can identify the individual with 100 percent accuracy," Laszlo said. "When Zhanpeng first came to me with the idea, I honestly didn't think it would work. It's amazing."

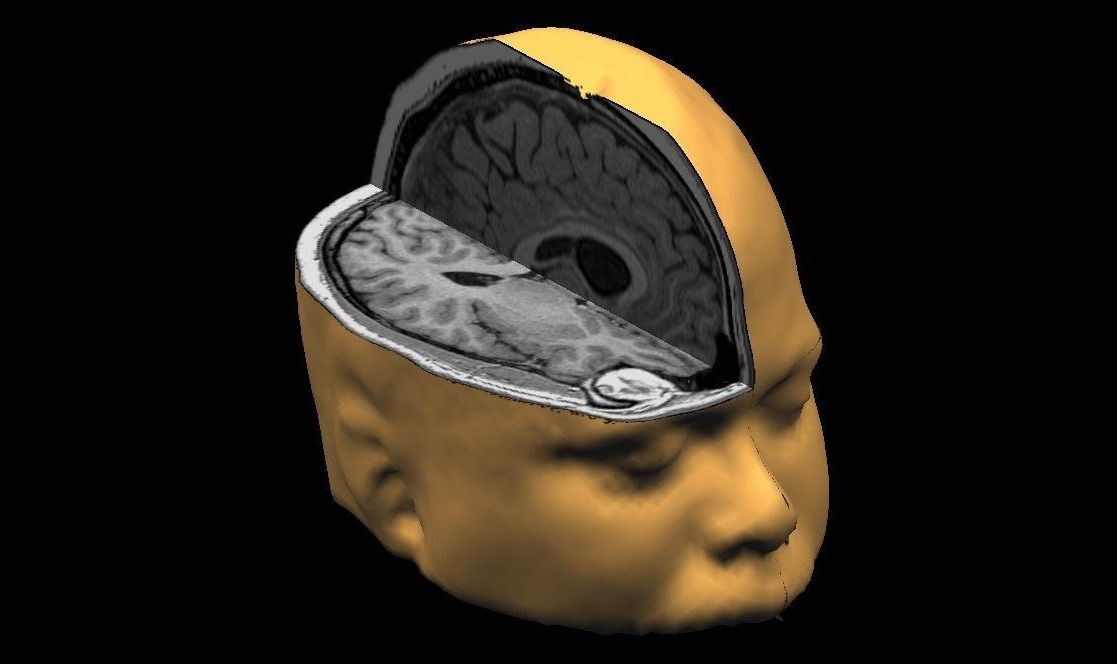

Laszlo and Jin's resulting study recorded the brain activity of 50 people wearing electroencephalogram (EEG) headsets. The participants were shown a series of images designed to elicit a reaction—such as a slice of pizza or a boat—which allowed them to uniquely identify each person.

While the cost and ease that brain-reading technology can be implemented means it is unlikely to be rolled out on any significant scale, the researchers suggest they could be used in "high-security physical locations, like the Pentagon or Air Force Labs."

There are several advantages that the so-called "brainprints" have over current biometrics used in identity security. Unlike fingerprints and retinal scans, brainprints cannot be secretly copied or taken from someone who is deceased.

"If someone's fingerprint is stolen, that person can't just grow a new finger to replace the compromised fingerprint—the fingerprint for that person is compromised forever," Laszlo said.

"Fingerprints are 'non-cancellable.' Brainprints, on the other hand, are potentially cancellable. So, in the unlikely event that attackers were actually able to steal a brainprint from an authorized user, the authorized user could then 'reset' their brainprint."

Correction| Sarah Laszlo's name was misspelt in an earlier version of the article.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Anthony Cuthbertson is a staff writer at Newsweek, based in London.

Anthony's awards include Digital Writer of the Year (Online ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.