For the first time ever, a drug targeting Huntington's disease was found to be safe—and possibly effective—in humans. To date, no direct treatment for the condition exists. The drug lowered levels of a toxic, mutated form of a protein that is at the root of this neurodegenerative illness, suggesting a path forward for treatment.

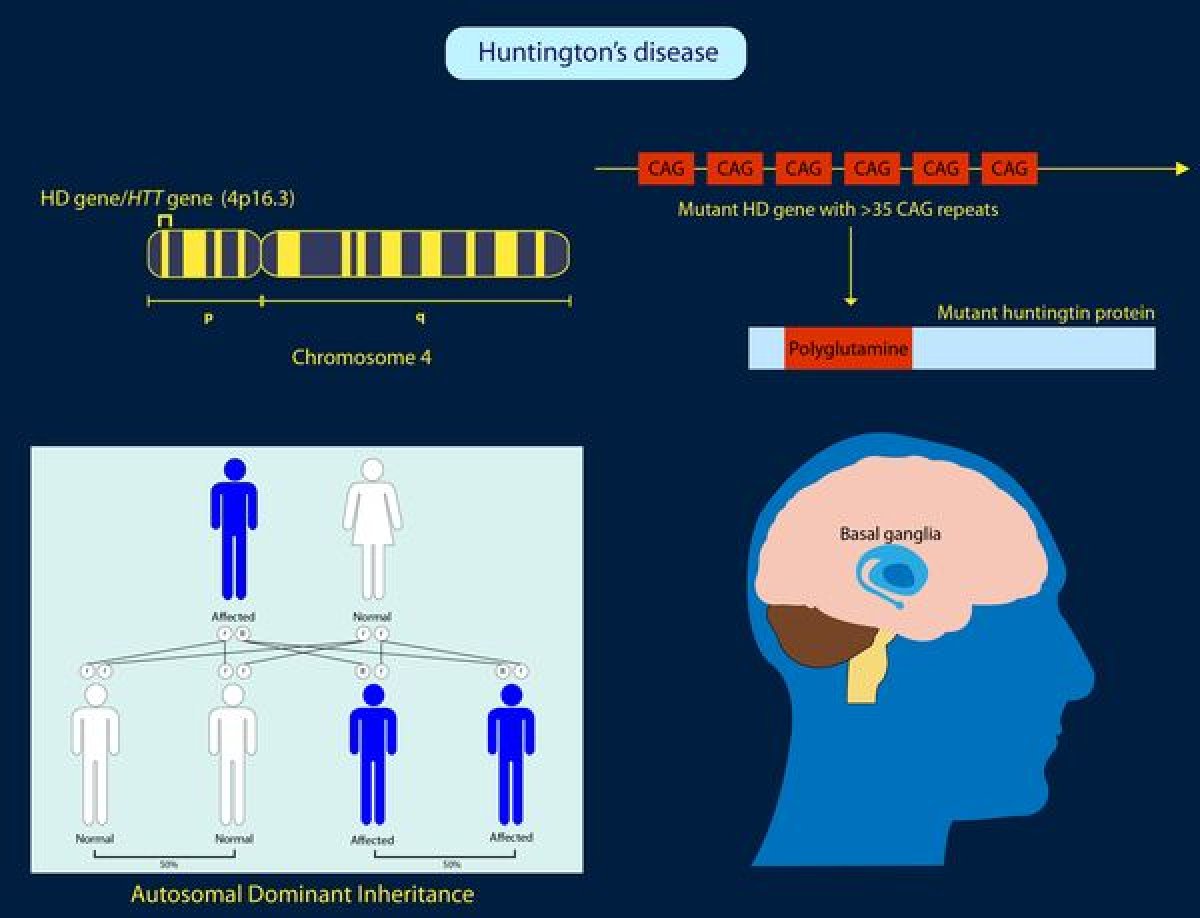

Huntington's disease is an inherited brain condition that affects 30,000 people in the U.S, according to Huntington's Disease Society of America. An estimated 100 per million Americans are living with this disease, for which there is no direct treatment. An inherited disease, Huntington's is passed down to anyone who carries the gene for it.

Huntington's can lead to mood swings, problems with movement and speech, and usually death within 15 to 20 years of diagnosis. According to the National Institutes of Health, the disease usually begins in people between the ages of 30 to 50. Although there are some medications available for symptoms of the disease, no treatment currently exists for the disease itself.

To study whether a new approach might finally work against this so-far impenetrable disease, researchers at University College London gave 46 people with early-stage Huntington's disease in Canada, Germany, and the U.K. the new drug, known as IONIS-HTTRx, via spinal injection. According to The Guardian, the drug was delivered in four injections once a month for four months. The amount of drug increased with each injection.

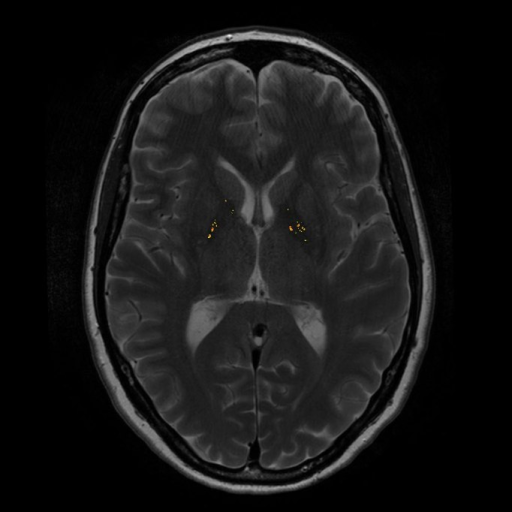

The results, which are expected to be published next year, showed that the experimental compound blocked production of the abnormal protein encoded by the genetic mutation linked to Huntington's disease. As the dose of the drug increased, the amount of mutated huntingtin decreased. The trial findings were announced by University College London on Monday.

"This is very exciting," Dr. Glenn Konopaske, the medical director of the Huntington's Disease Program at the University of Connecticut, told Newsweek. Konopaske, who was not associated with the study, has been closely following the research around the use of drugs that suppress the production of mutated huntingtin in mice. He was floored by the fact that the drug stopped neurogeneration in the animals.

Huntington's disease stands apart from other genetic disorders. For many genetic disorders, such as Tay Sachs or cystic fibrosis. a person may be a "carrier" of a gene linked to the disease but they don't necessarily develop the illness. With Huntington's disease, anyone with the gene also has the illness. Children of people with Huntington's disease have a 50 percent chance of inheriting the gene and developing the disease themselves.

Sarah Tabrizi, the neuroscientist in charge of the team behind the trial, told The Guardian the trial's results were "beyond what [she'd] ever hoped."

The researchers emphasize that the drug is still in a phase 1 trial. This stage of clinical trial is meant to test the safety of a drug or treatment in humans, so that its effects can be better studied in larger groups.

"A lot can happen between phase 1 and phase 2," Konopaske said. Still, he finds the results exciting. "I'm cautiously optimistic," he said.

According to The Guardian, the drug company Roche will be conducting a larger, longer trial to see if participants' symptoms improve. And if that works, Tabrizi thinks the drug could go further than slowing the progression of the disease: it could, she hopes, prevent it.

She believes the drug may one day be useful for people who have yet to experience symptoms of the disease. "They may just need a pulse [of the drug] every three to four months," she told The Guardian.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Joseph Frankel is a science and health writer at Newsweek. He has previously worked for The Atlantic and WNYC.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.