Scientists studying human cognition and long-term memory were surprised to discover that a key protein involved in those processes not only arose from a random evolutionary event hundreds of millions of years ago, but acts much more like a virus than a protein.

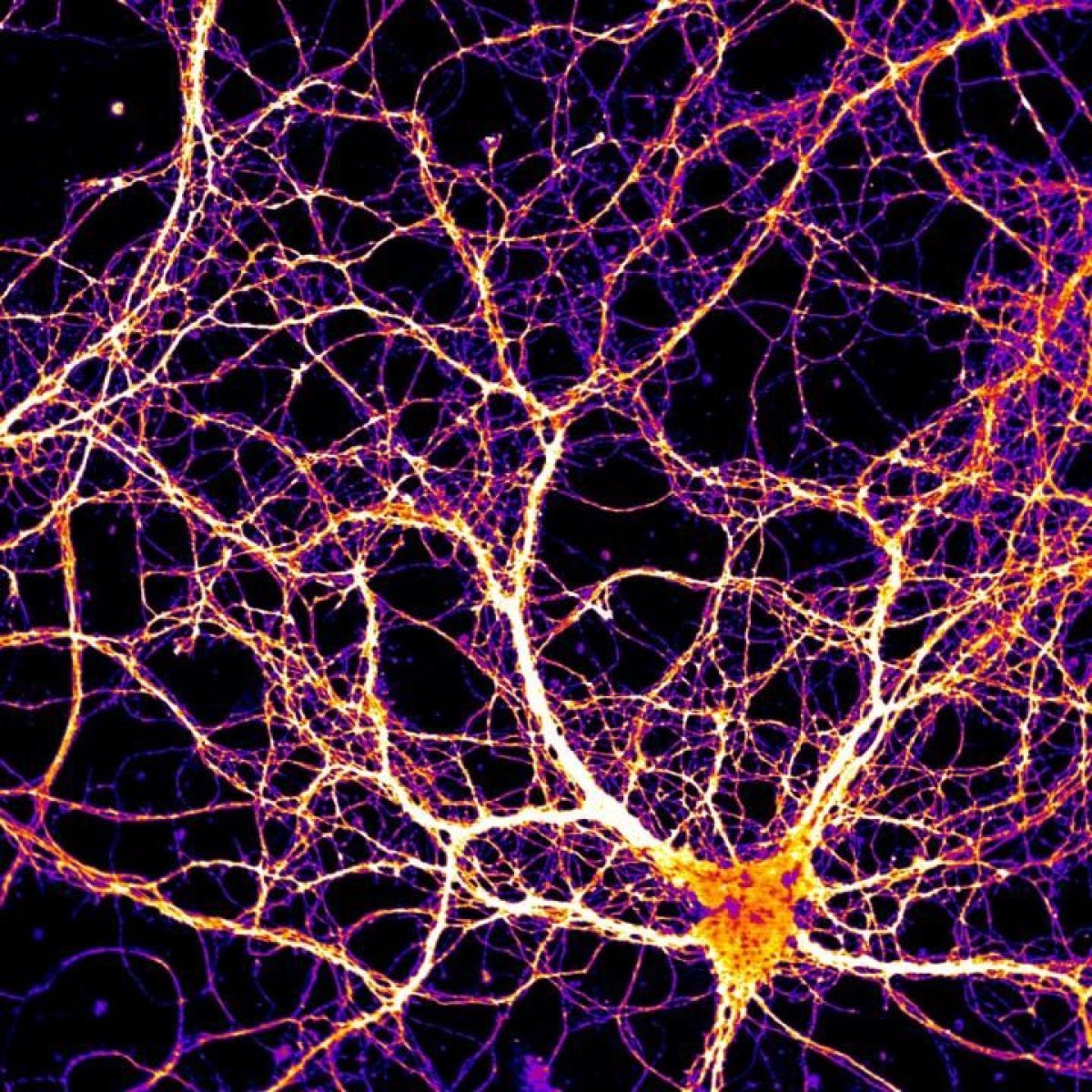

The protein in question, Arc, has characteristics similar to a virus that's infecting host cells. Virus-like proteins could mean cells within the brain have a completely unknown method of communicating with one another. This could in turn change our entire conception of human learning and memory formation, including how we research treatments for conditions like dementia and Alzheimer's disease. A paper describing the research was published in the scientific journal Cell.

"It's wild to think that our cognitive capacity and brain plasticity may have originated from a chance event hundreds of millions of years ago," senior author Jason Shepherd, a neuroscientist at University of Utah Health, told Newsweek via email.

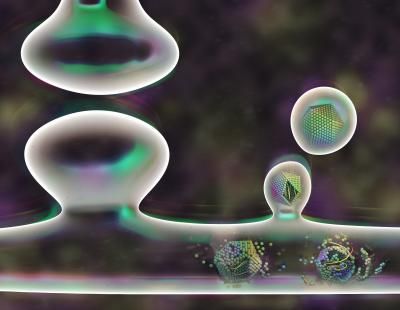

Shepherd became intrigued by Arc when he noticed that, structurally, it was shaped like a lunar lander capsule—a geometric-looking pod with "legs" extending downward. The structure is shared by the human immunodeficiency virus, better known as HIV. After realizing that parts of Arc's genetic code bore striking resemblance to viral capsids—the protective protein shells that surround them—he and a team of scientists from various research institutions designed a series of experiments to test the possibility that Arc didn't just look like a virus, but also acted like one.

It does. A virus invades a host cell and is ready to infect others when it emerges; Arc "invades" the brain's neurons, which activate to release the capsids and the genetic information contained therein. Arc is the first and so far only non-viral protein known to behave in this manner. Shepherd said he and his colleagues are now actively pursuing the possibility that Arc plays a role in Alzheimer's disease.

"The current thinking about memory formation hasn't taken into account intercellular communication at all," Shepherd explained to Newsweek.

Somewhere between 350 and 400 million years ago, an early form of retrovirus called a retrotransposon (a transposon is a DNA sequence that can switch up its position in the genetic code) shoved its way into the genome of mammals alive at the time. This formed the origins of a gene that enhances our brain plasticity and long-term memory formation.

Oddly, the researchers found that same thing happened again 150 million years later, just with flies. One explanation is lightning striking twice, but the researchers believe this means the pattern could have repeated at other critical evolutionary junctures. We just haven't found them yet.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kastalia Medrano is a Manhattan-based journalist whose writing has appeared at outlets like Pacific Standard, VICE, National Geographic, the Paris Review Daily, ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.