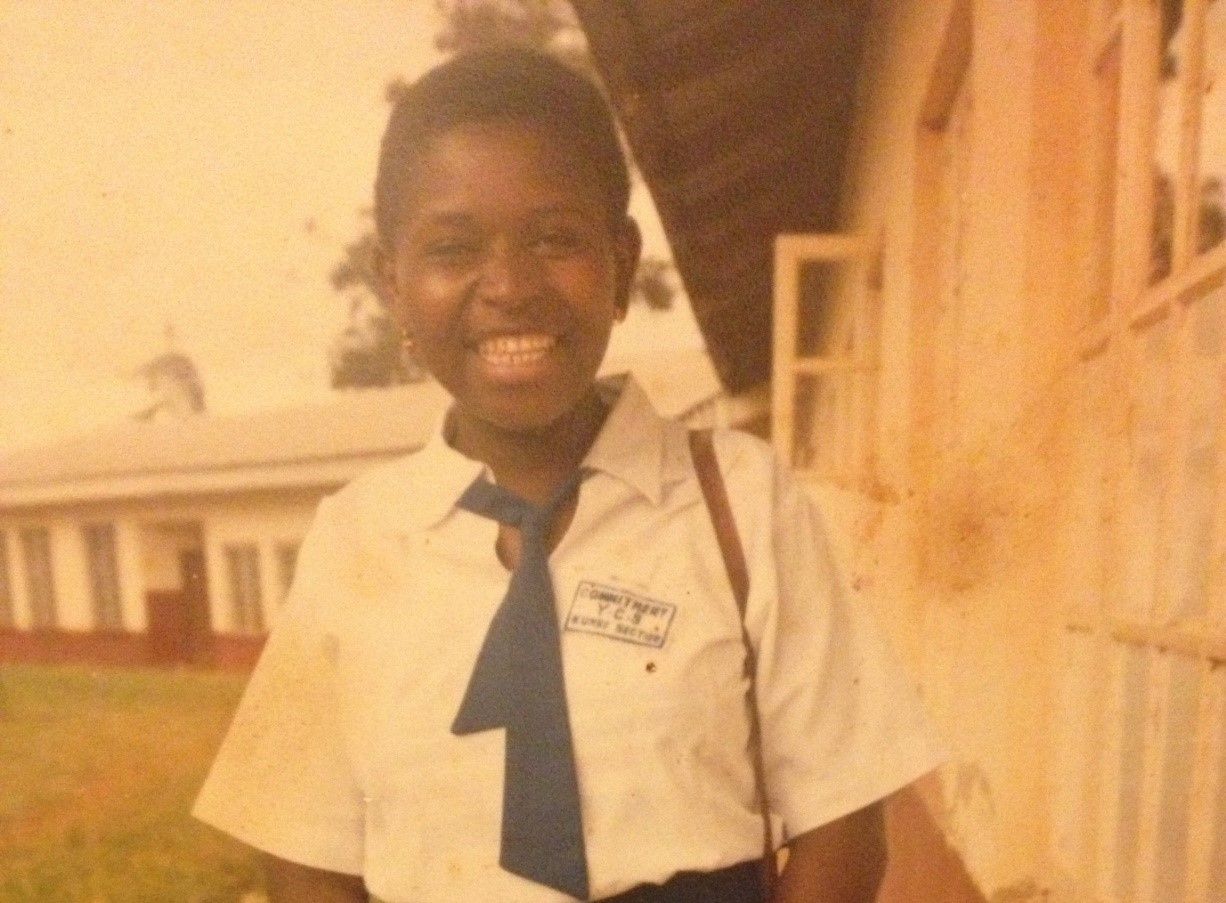

Victorine Ngamsha was 12 years old when, on leaving church one Sunday, her aunt told her they "needed to do something about her breasts." Vicky, now 43, recalls her aunt saying: "They are too big. Much too big. Come with me."

When they got home, Vicky's aunt told her to take her shirt off and sit down. "There were no men in the house, just women, so it didn't really matter that I was going to undress," says Vicky, who is originally from Kiyan, in north-west Cameroon. "She got large coffee leaves and heated them up over a stone fire. Then she pressed them onto my breasts."

Vicky, who has lived in Birmingham, England, for 12 years, now knows that what she experienced for the first time that day was a procedure called breast ironing, which involves pushing and massaging hot objects, sometimes stones and hammers, into a girl's breasts in an attempt to stop them growing.

In Cameroon, breast ironing affects as many as one in four girls, according to a 2006 report by a Cameroonian women's organization RENATA—also known as the National Association of Aunties in Cameroon—and Germany's Association for International Co-operation (GTZ). Humanitarian research organization the Feinstein International Center, in the U.S., has reported cases —sometimes under other terms, such as "breast flattening" or "breast sweeping"—in other countries across West and Central Africa, including Benin, Chad, Ivory Coast, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea-Conakry, Kenya, Togo and Zimbabwe. But Cameroon is where it happens most often.

British MP Jake Berry says the practice is also becoming more widespread in the U.K.—but the lack of official figures hide the extent of the problem.

On March 8—International Women's Day—Berry gave a speech in the House of Commons in which he said thousands of girls in West African communities in British cities such as Birmingham and London were falling victim to the "abhorrent" practice. Berry tells Newsweek he wrote to every police force and local authority in the U.K. to ask what they were doing about the issue: 72 percent of the police forces that responded either "failed to answer a question about breast ironing or admitted that they had never heard of it."

The British police's ignorance towards breast ironing is unsurprising to Vicky, who says growing up in Cameroon, you become accustomed to authorities "staying away from issues of the woman." When Vicky was 10, she was raped by a neighbor. Her perpetrator was never arrested, charged or convicted. "I was playing in the coffee fields, jumping around like a child does, and a gentleman came to me," says Vicky. "He said if he didn't do things to me, I would die like one of my sisters, Gisela." Six of Vicky's brothers and sisters, including Gisela, died of malnutrition. "I was only 10, so I didn't know anything. He made me lie down on the ground and do it with him," Vicky says.

"Afterwards, I ran to my mum with blood between my legs and she said, 'You naughty girl, you have been climbing orange trees, you have hurt yourself.' At first I told her I could not tell her what happened to me because I would die. But eventually, I did. I told her the man put something inside of me. I told her I didn't want to die and my mum burst into tears."

This was not the last time Vicky was sexually assaulted during her childhood, but it made her aware, for the first time, that being a woman meant being unsafe. As Vicky's body began to grow and develop, so did the fear of being vulnerable.

Breast ironing is often carried out as a means of making pubescent girls less desirable to men; the aim is to discourage premarital pregnancy, rape and sexual assault. Mothers or other female family members instigate the process when they fear a child is becoming exposed to sexual harassment or abuse, largely during puberty.

It was two years after her rape, when Vicky was 12 and edging tentatively into adolescence, that Vicky's aunt took her home after church and began to flatten her breasts for the first time. Vicky doesn't remember crying, but she does remember the searing pain of hot leaves on naked skin. "It was so, so hot, but my auntie said it would make me beautiful," she says. At 12 Vicky was unaware of the implications behind the process—that by making her appear less developed as a woman, she was believed to be at less risk of becoming pregnant and having to leave school. In Cameroon, a girl's education, reputation and career prospects are over if she has a child at a young age. "I was grateful—I didn't want to be ugly. I remember it hurting, and then saying thank you when it was done." Although Vicky does not explicitly connect being raped and having her breasts ironed, she remembers acknowledging that the practice served as a form of "protection." For her the process was repeated; she can no longer remember how many times.

After what Vicky calls a "challenging and humble" upbringing, she moved to Britain because of her husband's work. In the U.K., breast ironing is largely unacknowledged, particularly from an official perspective. By comparison, in July this year, the first annual statistics on female genital mutilation (FGM), the deliberate removal or cutting of a woman's labia and clitoris, recorded 5,700 new cases in England between 2015 and 2016, in a study undertaken by the Health and Social Care Information Centre.

Berry claims the way in which police forces record religiously or culturally motivated violence against women is not efficient enough. While FGM has been a specific criminal offense in the U.K. since 1985, with laws strengthened in 2015, the term "breast ironing" is barely recognized, let alone understood. "Since my speech I have been working closing with the Metropolitan police," says Berry. "Police forces are anecdotally aware that the practice is happening here on British soil, but there are no official statistics. This is partly due to the way in which the police have historically recorded instances of breast ironing. At the moment, there is no 'breast ironing' tab on their system, for example. Instead everything is filed under 'honor-based violence' and the specifics are lost.

"The lack of statistics are also down to the private and secret nature of the practice; it is done by family members and not many people are willing to report their loved ones."

The Home Office tells Newsweek that breast ironing is considered illegal as it falls under the category of child abuse. The Minister for Vulnerability, Safeguarding and Countering Extremism, Sarah Newton, says political or cultural sensitivities "must not get in the way" of preventing and uncovering the practice.

Margaret Nyuydzewira, founder of the CAME Women and Girls Development Organisation, a U.K. charity campaigning on behalf of breast ironing victims, believes cases of the practice are likely to be increasing due to significantly expanding West African communities in Britain, mainly in London and Birmingham. Home Office figures show that from 2001 to 2015, 6,972 Cameroonians immigrated, claiming asylum or citizenship.

"It is a brutal procedure, both immediately because of the pain and trauma, and affecting the victim well into adulthood," says Nyuydzewira. "People are doing it with good faith, they believe they are protecting their daughters, but it is harmful. Children are undergoing months of abuse every day and authorities in the U.K. are afraid of interfering in a culture they do not know much about. CAME has estimated that up to 1,000 girls in the U.K. have been subjected to breast ironing."

The practice ranges dramatically in its severity, from using heated leaves to press and massage the breast, as in Vicky's experience, to using a grinding stone to burn and crush the budding gland. The psychological scars can be deep and long-lasting. According to Cameroonian gender consultant Awa Magdalene, such practices "rob girls of the self-confidence they need to assert themselves in society later on in life."

As well as the pain and psychological trauma, breast ironing exposes girls to multiple health problems. According to medical experts, it can lead to abscesses, itching, the inability to breastfeed—a critical problem in parts of Cameroon, where infant milk formula is expensive and not always easily available—infection, deformity, cysts, tissue damage and even breast cancer. "I had one girl who died of breast cancer aged 24," Sinou Tchana, a Cameroonian doctor, said to the Inter Press Service in 2011. "You can have breast cancer in the cases in which the ironing is so intense that it destructs [sic.] all the breast tissue."

The lack of knowledge about breast ironing and the familial nature of the way it is conducted makes it difficult for social services and law-enforcement agencies in the U.K. to intervene. Getting victims to testify against their family is difficult: women often justify their experiences by recognizing the good intentions of their parents and investing in the promise that it is a preventative measure. Only when they are much older do they realise the severity of what they went through, but even then, they do not want to inform the authorities.

"I want there to be statistics, but I am skeptical," Berry says. "This is a horrific crime against women and I want it to be a crime, but as we've seen with cutting [FGM], making something a crime does not lead to prosecutions or convictions. (In September, a British parliamentary committee reported that the U.K.'s failure to successfully prosecute a single case of FGM was a "national scandal." Only one FGM prosecution has been brought to trial since 1985 and both defendants in that case were cleared last year.)

Berry, much like Margaret and Vicky, believes that the first step is to make breast ironing as widely acknowledged and as understood as FGM. He says: "Although awareness of FGM is probably at an all-time high, the practice of breast ironing will remain hidden unless we speak out about it wherever we can. This idea that puberty, the natural development of a woman's adult body and the natural journey to maturity can be violated as part of some mistaken or bizarre belief system has no place in our society."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.