President Barack Obama is just one of the many international leaders to urge the people of the United Kingdom to remain members of the European Union. But in doing so he is asking British voters to accept policies and institutions that the American people would not accept for themselves. I'm not just guessing that this is the case. An opinion poll by YouGov found that only 29 percent of Americans would agree to Mexicans having an automatic right to live and work in the U.S. in return for Americans enjoying such a right in Mexico. Even fewer—19 percent—supported the idea of a joint Canadian-Mexican-American high court that would be the ultimate decider of human rights questions. Only 33 percent supported a "South and North American Environmental Agency" that would regulate the fishing industry across the Americas.

As members of the 28-state EU, the British people are subject to the decisions of a supranational and highly politicized court; they watch as jobs in their neighborhoods are taken by Romanians, Bulgarians and other Europeans; and they also find that bureaucrats in Brussels rather than elected representatives in the House of Commons decide all key environmental, fishing and agricultural matters. Britain is only a fraction of the democracy that it was in 1973, when we joined the European Economic Community.

I highlight European Economic Community because most British people thought that was what they were joining. They were reassured by the prime minister of the time, Edward Heath, that they would not lose sovereignty, but they have. They and their elected representatives can't stop mass immigration from other parts of the EU. Decisions by British courts to deport terrorists and criminals can be overruled by European courts. The British Parliament can't even cut certain taxes because of European laws.

The EEC has been superseded by the powerful Brussels-based European Union, but the politicians, bureaucrats, central bankers and judges who run it haven't finished delivering even deeper integration. Italian Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, for example, has said: "I dream, think and work for the United States of Europe." President of the European Commission Jean-Claude Juncker has tweeted that "we will need a European army. Because we have to be credible when it comes to foreign policy." My fear is that such an army will become a rival to NATO and will be used by EU nations that already spend too little on their defense, as an excuse to spend even less.

I have no doubt that the British people would not have joined the EEC if they had known what it would become. However, today, some fear leaving, and their fears have been stoked by the Remain campaigners who have warned that recession and even military conflict might be the result of Brexit. Prime Minister David Cameron rarely makes a positive argument for the EU, and in one of his most irresponsible interventions, he even said that leaving would put a bomb under the U.K. economy.

When it was the EEC, the European project played an important role in knitting together a once-warring continent. As history has repeatedly shown, when nations are joined by trade, they are less likely to fight. But as the EEC has morphed into the EU, the more recent initiatives by the continent's leaders to abolish national currencies and borders have started to undo this good work by creating social pain and political extremism. The eurozone, for example, has produced unnecessarily harsh austerity and unemployment across southern Europe. Only Antarctica has grown more slowly than the EU economy over recent years. The borderless Schengen zone has, according to Interpol, been exploited by terrorists, human traffickers and criminal gangs. The result, across Europe, has been despondency and the election of extreme governments and politicians.

Britain should continue to trade with Europe and be a good neighbor to our friends on the continent, but we don't want to be any part of what it has become and what it plans to become. As the only major nation in the world to spend 0.7 percent of our national income on overseas aid and 2 percent on defense, we will always play our full part in helping build a fairer, more prosperous world, but remaining part of a dysfunctional, declining EU is not sensible. The problem is not the so-called "Little England" mentality of which the prime minister and others have accused us, but Little Europeanism. On June 23, I hope Britain will correct the terrible mistake it made in 1973 by restoring its democracy and rejoining the world.

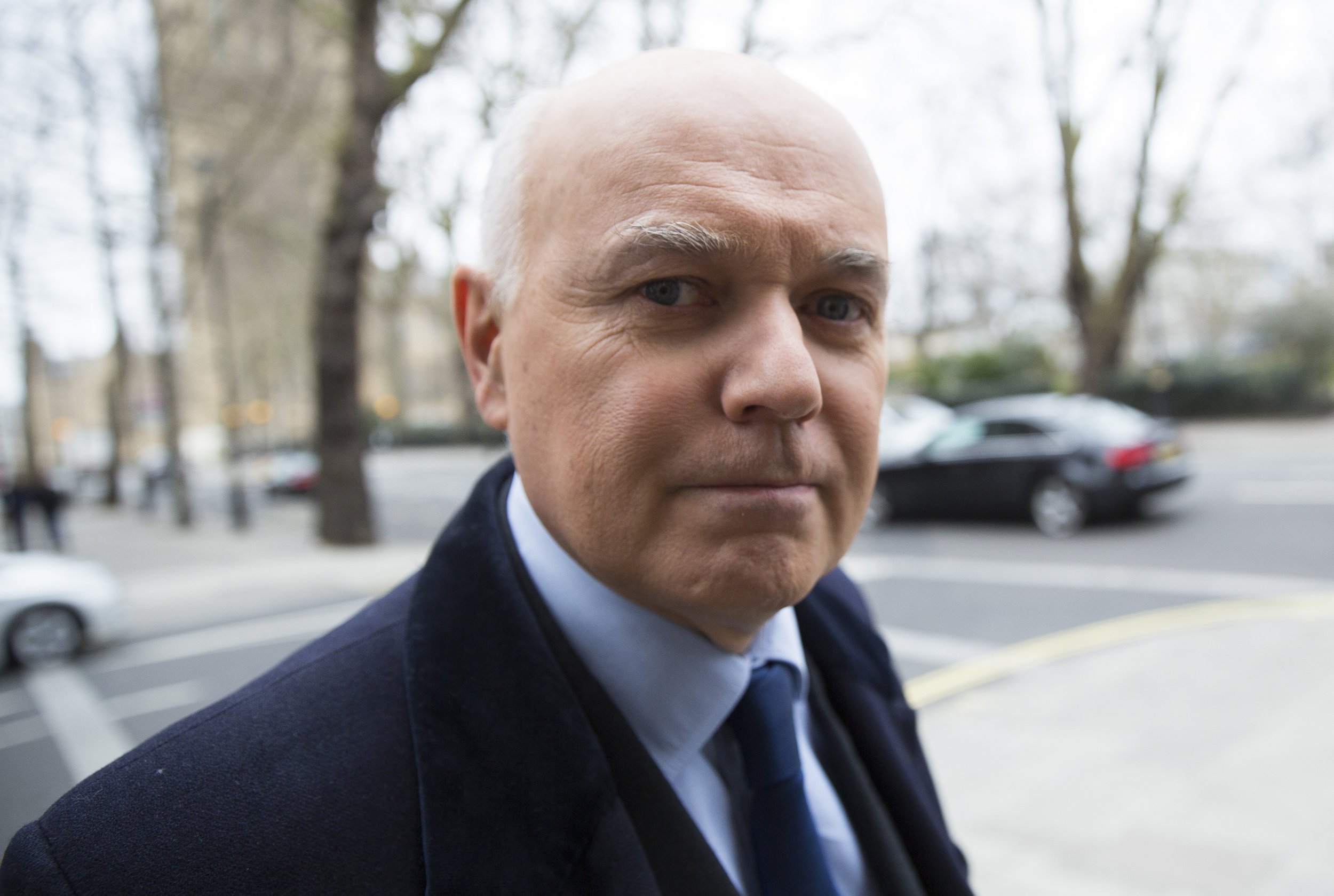

Iain Duncan Smith was leader of the Conservative Party from 2001 to 2003, and the secretary of state for work and pensions from 2010 to 2016.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.