Arguably Turkey is one of the major casualties of the Brexit vote. The fear of Turkish migrants washing up on British shores was used by the Leave campaign in the run up to the June 23 referendum. In the end, the U.K., which was considered the most supportive EU country of Turkey's accession negotiations, will no longer be there.

Paradoxically, the U.K.'s exit may make it easier for Turkey to reconcile itself to the inevitable, that the likelihood of its accession to the EU was actually close to zero. The future EU will be one bound by two powerful NATO members, each with their own free trade agreement with the bloc.

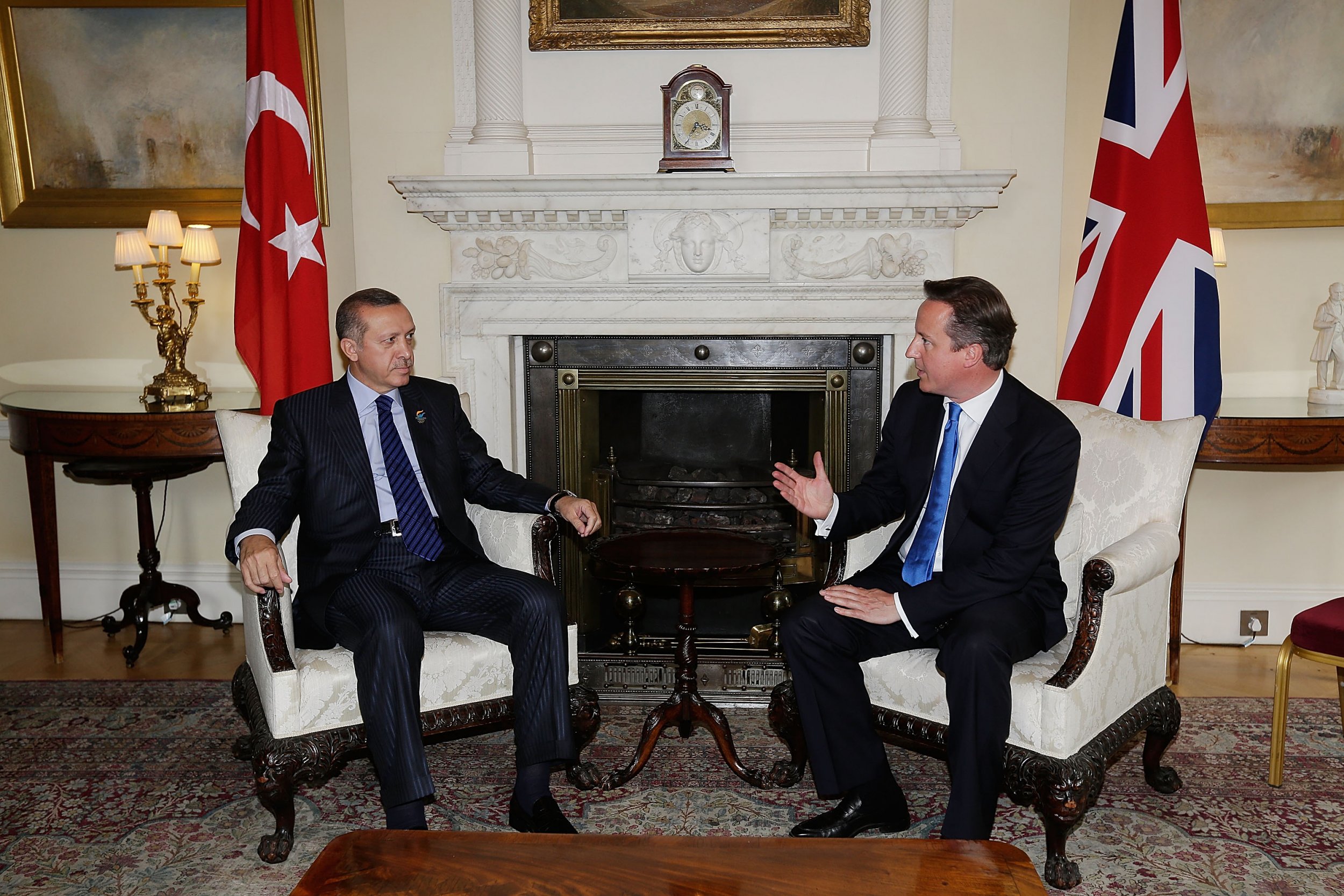

The damage done to Turkish membership prospects by the Brexit campaign and its outcome is twofold. There is no question that the conjuring an image of over one million Turkish immigrants, however false this premise may have been, further sullied an already problematic Turkish image. The use of Turkish immigrants was deliberate and cynical; at a time of large numbers of Arab and African refugees are coming to Europe, Muslim Turks from a prospective member country provided a convenient scapegoat. At the same time, Prime Minister David Cameron made things worse by declaring that at the current pace of negotiations Turkish accession was unlikely to happen before the year 3000.

As derogatory and cynical these ploys and counter-ploys may have been, the fact is, that in the aftermath of a vote to quit the EU, what the British think may no longer be relevant.

The UK's leave vote will complicate matters for Turkey in the near future simply because Europe and the British will be consumed by the intricacies of managing the exit process; a process for which there is no precedent, let alone preparation. This is uncharted territory and it is likely that other EU priorities, including the immigration crisis, the Turkish file will not get much attention. How does one manage negotiations with Turkey while everyone else is focused on the modalities of the U.K. exit, not to mention the added complications a Scottish referendum may also bring to the table?

If anything, the Brexit process will provide the Europeans with a convenient excuse for delaying negotiations with Ankara. Certainly many European capitals will be cautious and reticent to talk of Turkey when their populations are disillusioned and angry and the rise of the extreme right represents a real challenge.

Turkish accession, however, has been in real trouble for some time. Between the Cyprus problem, the size of the population and the real descent into authoritarianism under the current government, the prospects of accession even in the medium-term have been poor. Turkish response to this unfavorable situation has been a mix of resentment and anger towards Europe, yet a continued determination to proceed with negotiations. The diatribe against European hypocrisy dominates political discourse and the airwaves. Certainly the ruling Justice and Development Party's (AKP) attempt to revitalize Turkey's Ottoman legacy can be seen as both a genuine attachment to the past and as a means to build Turkish psychological defenses.

However, with Britain out of the EU, there may be not be any shame in not being a member. Brexit makes it easier for Turkey to accept the reality that membership was a fast disappearing mirage. Ironically, the U.K. will be seeking something that only Turkey enjoys with the EU: a free-trade agreement.

Its desire for EU membership notwithstanding, Turkey is closer to Britain now in its desire not to subordinate national preferences to rules that are conjured in places like Brussels. Nowhere is this more evident than in foreign policy. Turkey has, especially since the advent of the AKP, pursued foreign policy objectives that have put it at odds with its allies.

Britain and Turkey represent mirror images of each other: on the edge, but not the periphery, of Europe, two powerful NATO countries with traditions of acting independently and jealously trying to protect their cultural and political distinctiveness. Turkey can derive sustenance from Brexit and may find that it is more likely to be acting in concert with the U.K. than with Europeans. With Brexit, therefore, Turkey may finally find a more comfortable place for itself.

Henri J. Barkey is the director of the Middle East Program at the Woodrow Wilson Center. Follow him on Twitter @hbarkey.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.