The purpose of great national collections like the Smithsonian or the British Museum must be to explain the world to itself. And in just this spirit, the British Museum has launched an exhibition that focuses not on art or artifacts but on the history and meaning of Islam's kinetic heart, the hajj.

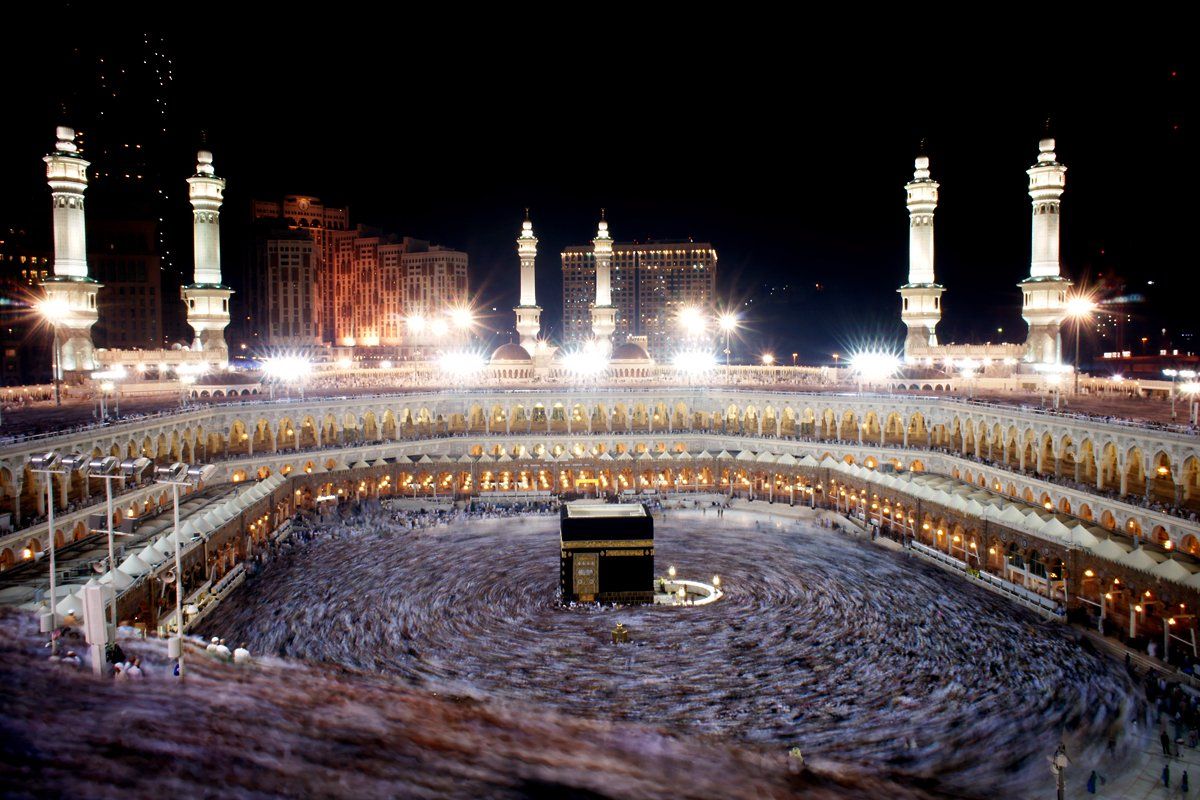

At its center stands the mysterious Kaaba, a cubic building containing a meteorite venerated in pre-Islamic Arabia. It was, according to legend, raised by Adam, restored by Abraham, and cleansed of its pagan idols by Muhammad, who made his hajj in 632, the year he died. He observed the sacred rituals and told every Muslim of sound mind and clear conscience to do the same. Ever since, the rituals observed in memory of Abraham and his family have been performed in the last month of each Islamic year.

It is rather wonderful to learn that until oil was discovered in the 1930s, the hajj was Arabia's main source of income. The numbers then were relatively small, reflecting the dangers and rigors of the pilgrimage. An arduous desert journey had become longer and more challenging as the faith expanded and pilgrims from Syria and Cairo were joined by others from Afghanistan, West Africa, and Indonesia. Early artifacts from the exhibit include a desert milestone marker, and gold coins used to pay off marauding Bedouins; later ones include guidebooks and illuminated recitals of the journey, not all flattering to the Meccans. Death and danger awaited the pilgrim traversing the barren wastes of North Africa unless, like the king of Mali in 1324–25, he could travel with a retinue of 8,000 men, spending his gold so freely that Egypt suffered from inflation. Conrad's Lord Jim was inspired by the true story of an overloaded pilgrim ship crossing the Indian Ocean; by the late 19th century so many pilgrims came from the British Empire that Thomas Cook was briefly appointed to run the operation.

The hajj is, in fact, a bellwether of the state of Islam. When rulers were powerful, they could impose themselves upon the hajj: affording pilgrims protection and assistance was one of the defining roles of an Islamic monarch. Behind this exhibition, funded by the Saudis, one detects a palpable air of self-congratulation and a tendency to soft-pedal the role of the Ottoman Turks in maintaining the major hajj routes across their empire from the 16th to the 20th centuries. The only year when the hajj was suspended was 1917, when the Arabs rose in revolt against the tottering Ottoman state.

Dynasties like the Abbasids of Bagh-dad, the Mamluks of Egypt, and the Ottomans from Istanbul sent out huge hajj caravans every year. The tribes were paid off, the wells and water tanks properly maintained, the cities adorned and made safe and comfortable. When shocks struck, the system could collapse. Then the inhabitants of Mecca were revealed in all their greed, fleecing the pilgrims; the Bedouins would attack, so that in 1757, 20,000 pilgrims died from Bedouin strikes, thirst, and heat; battle could be taken even into the holy places. As early as 684 the Kaaba was destroyed, and in 930 the Black Stone was wrenched from its moorings and carried off into the hills.

Arrival at Mecca was a time for religious ecstasy, prayer, and thanksgiving. Only Muslims were, and are, entitled to visit Mecca. British explorer Sir Richard Burton, who did the journey in 1853 disguised as an Afghan doctor, shared their euphoria—though, "to confess the humbling truth, theirs was the high feeling of religious enthusiasm, mine was the ecstasy of gratified pride."

Pilgrims are housed in a tent city in Mina. From there, they come to circle the Kaaba counterclockwise seven times; later they must collect 49 stones the size of chickpeas, to cast against three pillars (housed within the Kaaba) in a symbolic renunciation of the Devil. In the meantime they will reenact Hagar's desperate search for water by running, if they can, seven times between two low hills.

To walk seven times around the Kaaba, in whose direction Muslims all over the world pray; to tread the sacred ground, reenacting rites performed here for so many centuries; and to share it all with such a varied crowd, is to feel part of a huge community of the living and the dead. Now pilgrims land at the nearby airport and are bused from one multistory destination to the next, sharing the experience with a staggering 3 million fellow believers. They come from all over the world, speaking different languages, and by a brilliant effort of logistics they are fed and watered and put through their paces.

Some of the objects on display in the museum's exhibit include the diary of the king of Boné, neatly written in the Bugis language; Burton's water flask; the whisk and cloth with which St. John Philby, a Muslim convert and father of the notorious Cold War spy Kim, helped to clean the Kaaba as a special honor; a mahmal, a richly embroidered canopy that was carried by camel from Istanbul each year; and the impeccable 2006 schoolbook diary of a 10-year-old English girl: "Words cannot describe the emotions that are created when one looks at the Ka'ba, such a simple object structurally yet so majestic and awe-inspiring."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.