Every summer, the Edinburgh Festival Fringe in Scotland stages thousands of productions, most of which are never heard of again, however good they are. It took an American portrait painter with a passion for theater to do something about this. The Carol Tambor Best of Edinburgh Award, established in 2004, is not so much a drama prize as a young writer's dream—the winning show lands a New York transfer off-Broadway, all expenses paid.

Related: German theater director takes on the far right

The latest beneficiary, which begins previews February 8 at 4th Street Theatre, is Life According to Saki, the first play by a young Englishwoman, Katherine Rundell. The Tambor judges have chosen well. To those who know her, it's been obvious for years that Rundell was going to be a star. The only question was in what field, as she is also an acclaimed children's novelist, a fellow of Oxford's smartest college and a tightrope walker.

'Obsessed' With Saki

The subject of Rundell's (rhymes with bundle) play, Saki, was an Edwardian reporter—real name H.H. Munro—whose short stories were witty, macabre and highly influential. "He wrote in the vernacular of the drawing room," Rundell wrote in the London Review of Books in 2015, "but with the ruthlessness of an avenging prophet." His fans have included A.A. Milne, P.G. Wodehouse and Roald Dahl, who said the best of Saki was "better than the best of just about every other writer around." But while Dahl, Milne and Wodehouse never faded away, Munro is half-forgotten. "The thing about Saki," Rundell tells me, "is that almost nobody has heard of him, but almost everyone who has is obsessed with him."

Her passion was shared by Jessica Lazar, a friend and fellow doctoral student with some directing experience, who suggested a play about Saki. They spotted a peg approaching: the centenary of his death, at age 45, in World War I. "It's such a Saki-ish story, the way he died," says Rundell, 29. "Going through no man's land in the dark and someone lit a cigarette, and a German sniper saw it, and his last words were 'Put that bloody cigarette out.'" She read up about him, seeking out the few of his letters that survived. "Ethel, his sister, burnt a lot of them. She was quite wary because he was gay"—this at a time when homosexuality was still an imprisonable offense—"and she seems to have known it. She called it 'chumming.'"

Rundell set her play in the trenches, where her Saki tells stories to divert the younger soldiers, who act them out. "It was a fascinating learning curve about the theater. With books you can be a little bit more nuanced. I'm sure this isn't the case with Tom Stoppard, but I found I had to be more punchy." She has made further adjustments for America. "I've winnowed back the talking. I'm never happy with anything I've made, and in Edinburgh it was a bit too intellectual. Now it's just about Saki's love for the men, and the men's love for Saki, and the bitterness of war and what stories might do for them."

Life's Aspiration

Stories are the fabric that holds her own incarnations together. "I wanted to be a writer," she says, "from the moment I knew that writing was a profession." Rundell grew up in a large family of British expats in Zimbabwe, where her mother taught French and her father was an aid worker for the British government. "I have no memory of not knowing, with a kind of fierce certainty, that I wanted to be a writer. My parents said to me, 'It's a difficult profession, but of course you can do it.' And I found out when I was about 20 that they didn't believe that at all."

By then the Rundells had moved to Brussels, a culture shock for Kate, who was 14. "In Zimbabwe, school ended every day at 1 o'clock. I didn't wear shoes, and there was none of the teenage culture that exists in Europe. My friends and I were still climbing trees and having swimming competitions." She gives Belgium some credit for broadening her mind: "The useful thing that moving around gives you is a sense that there can't be one correct way of doing things." But she resented it too, to the point where all her books, and her play, contain a joke at Belgium's expense. "It's a kind of ongoing, lifelong revenge."

When she went to St. Catherine's College, Oxford, to read English, the girl who missed climbing trees began to climb buildings. It started with a book she found, The Night Climbers of Cambridge, written in 1937 by an undergraduate who liked to shin up the city's spires with his friends and, in a modern touch, take pictures of each other. They were proper climbers, Rundell says, and she is not. "But there are lots of rooftops you can get onto in Oxford, and the views are so beautiful. Oxford can feel a bit claustrophobic, a bit pressured, unknowable, and then suddenly you get that carnival spirit of childhood. You do it with friends, and it's a very happy thing to do." She now climbs buildings in London, where the sight she treasures is Piccadilly at night, lit up "like a tsar's palace." The climbing led to tightrope walking: She has a dream to walk a wire across the Thames.

Aiming high seems to have become a habit. She applied for one of the two annual fellowships awarded by All Souls, the Oxford college open only to recent graduates, who have to sit for a notoriously daunting set of exams. Rundell spent three hours scribbling away about a single word: novelty. "I wrote about Derridean deconstructionist theory and Christmas crackers," she later told The Bookseller. "I feel like they let me in despite rather than because of it."

A fellow of All Souls at 21, she was free to study anything she choose—as well as teach people barely younger than she was—and embarked on a doctoral thesis about John Donne, which she recently finished. Rundell longs to write a popular book about him. "The thing I'm working on is how do you entice people to read an entire book about a poet and his poetry, against their will, because I think he is the greatest writer, ever, maybe. I mean, Shakespeare is tougher, bolder, but for a kind of intricate, bone-deep knowledge of the human heart, I think it's Donne."

Writing for Children

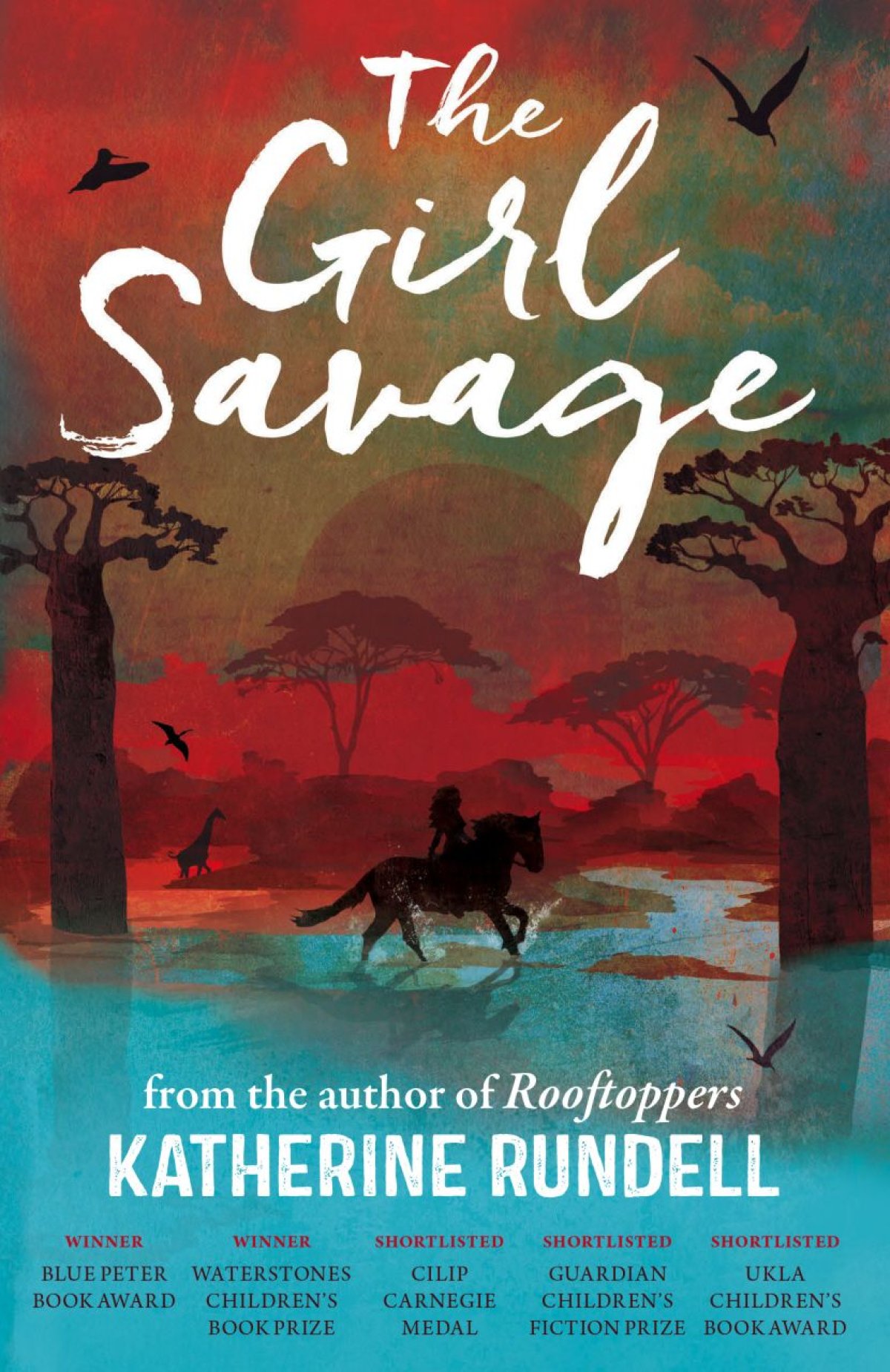

She found some at All Souls were sniffy about children's authors, as if their job too didn't involve enlightening young minds. Undaunted, she started writing books for older children that can also be relished by adults. Her first, The Girl Savage , is about a girl from Zimbabwe who is sent to an English boarding school. Her second, Rooftoppers, about an abandoned girl in Paris who becomes a tightrope walker, won the 2014 Children's Book Prize from the British bookshop chain Waterstones. She likes to give each story "some proper peril in the middle, and at least one strong female character, because not all books have them. And a lot of food, always."

The formula reaches its apogee with her third novel, The Wolf Wilder, which focuses on a fabulously spirited child called Feodora. "Once upon a time," it begins, "about a hundred years ago, there was a dark and stormy girl." You know instantly that you are reading a fairy tale with a modern twist. Slowly, deliciously, it turns into a thriller set against the backdrop of the Russian Revolution. Racing through Rundell's brisk, bright sentences, you see why her idol, Philip Pullman, called her "a writer with an utterly distinctive voice and a wild imagination." For Rundell, this seems to have been the ultimate trophy: "It was like getting a nod from Shakespeare. I think he's the best living."

The French film director Jean-Luc Godard famously declared that all you need to make a movie is a gun and a girl. Rundell, whose book demands to be filmed, has written a scene involving a gun, a girl and a wolf giving birth. Because wolves loom large in her story, she thought she'd better go and meet some, so a friend took her to a wolf sanctuary in the Brecon Beacons, on the English-Welsh border. "Just one thing," her friend said as they drew near. "You can't handle the wolves if you've had any cuts recently. When they smell blood, they bite."

This gave her a sudden quandary as she chews her nails. "Then I thought, I've come this far, and all I do with my hands is type. I only need five fingers." She emerged unscathed; maybe wolves can't smell sangfroid.

Life According to Saki will be staged at the 4th Street Theater, New York, from February 8 to March 5.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.