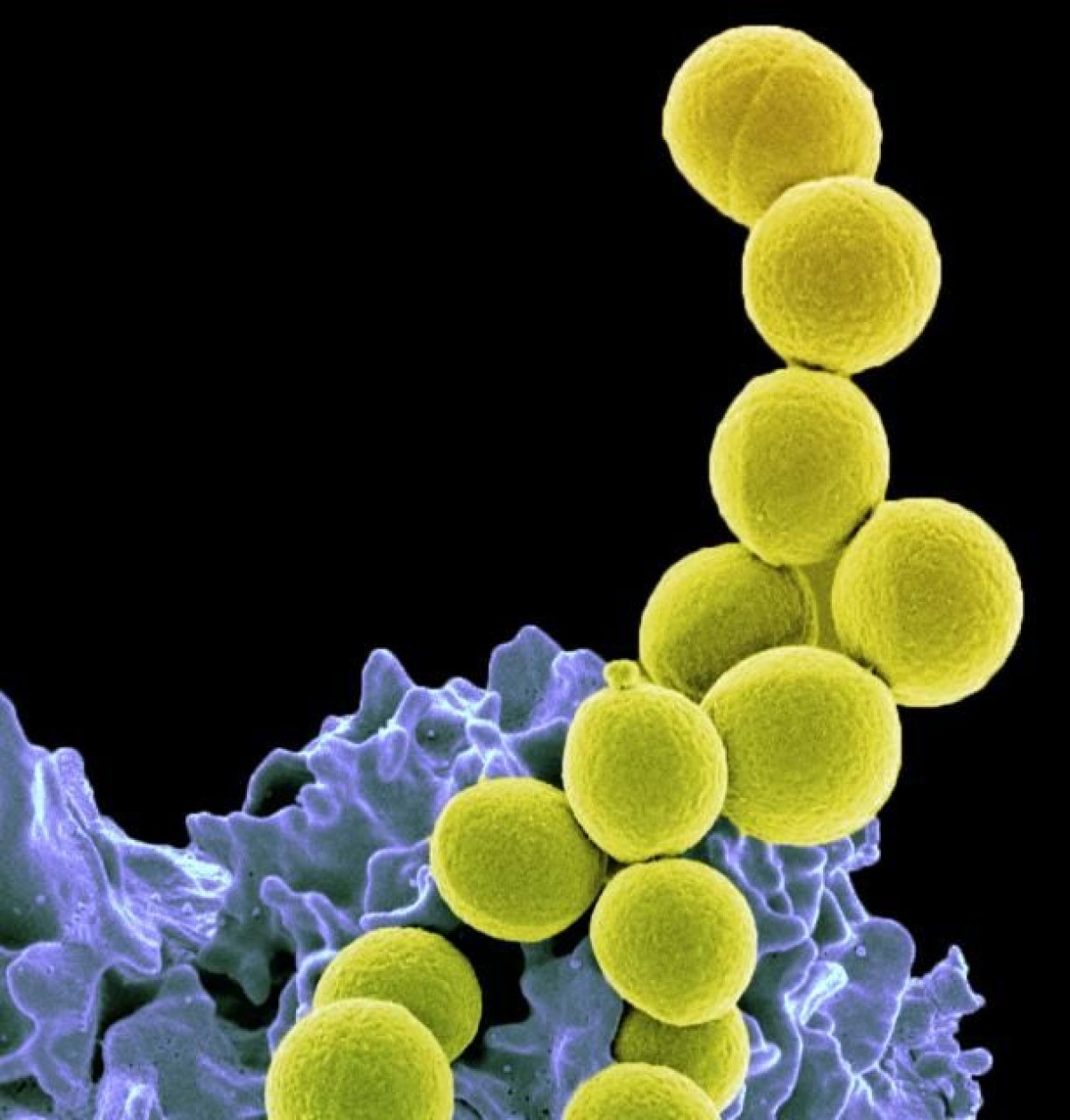

Death by sepsis is far from uncommon. A third of hospital deaths are caused by this complication of infections, which causes organ dysfunction. New research has identified a pathway that researchers believe is somehow responsible for this complication in some people. That research was published in Science Translational Medicine on Wednesday.

The immune system is hyperactive in patients with sepsis. Researchers from China and the U.S. wanted to understand what cellular mechanisms were behind that overdrive response. If they could find the underlying cause, then perhaps they could find a way to stop it. Their investigation lit upon a protein called STING, which can make a cascade of other proteins create an immune response.

After screening several potential drugs, they found one that seemed promising. The drug the scientists tested in the paper is called ceritinib and is marketed as Zykadia to treat lung cancer that has spread. It works by interfering with a protein called ALK, which gives STING the signal to start the domino-like pathway that eventually leads to sepsis.

Because ceritinib suppresses ALK, it can also prevent STING from kick-starting part of the immune system. Some lung cancer patients might find the name ALK familiar: Drugs that block ALK are currently used to treat some of these malignancies.

Ceritinib is fairly expensive; estimates range from over $6,000 per month in the U.K. to $13,200 per month in the U.S., one doctor told Medscape. "It is important to assess the cost-effectiveness of ceritinib versus other ALK inhibitors in the treatment of sepsis in the future," Dr. Daolin Tang, a surgeon at the University of Pittsburgh and one of the authors of the paper, told Newsweek. (Tang noted that their study did not get financial or material support from Novartis, the company that produces the cancer drug they tested.)

That research would be important if this lead panned out. That's not guaranteed. The study was done primarily using mice, not humans, and Tang and his colleagues didn't wait for the mice to look sick before they treated them. "The inflammation and immune response of sepsis is extremely complex and might differ between humans and rodents," Tang said.

"The conclusions were interesting," Dr. Ted Standiford told Newsweek. Standiford is chair of pulmonology at Michigan Medicine and was not involved in the research. "The relevance in a human system still is pretty unclear to me. Regardless of that, the identification of potentially new targets is relatively exciting."

Treating the mice before they appeared to be sick was Standiford's major criticism of the paper, though he emphasized that this approach is relatively common in sepsis research. "By the time we see patients with sepsis, they're already pretty sick. This has been a problem with many of the targets that have been identified in the past," he told Newsweek. Some treatments identified this way have failed in clinical trials as a result.

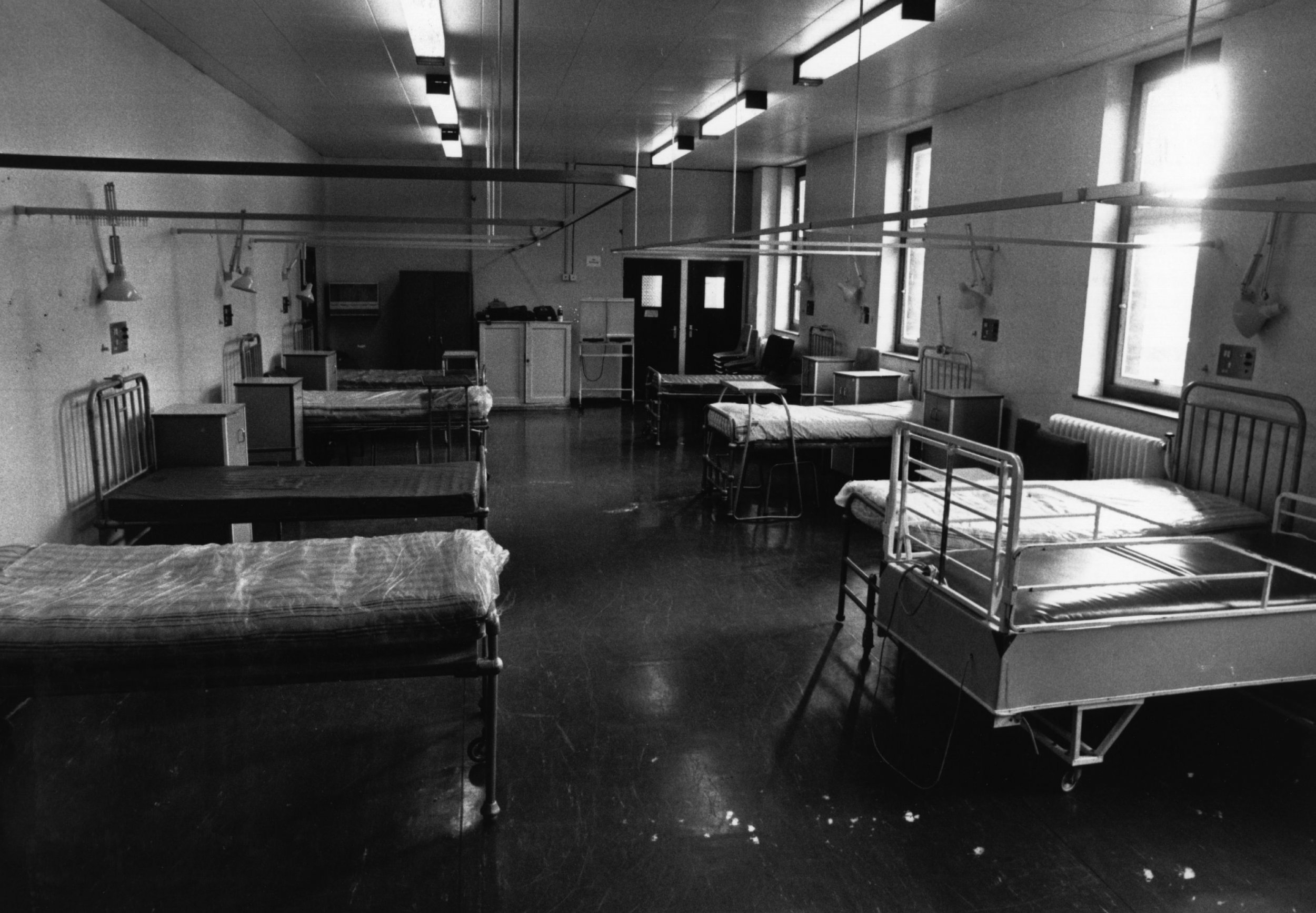

A number of different infections are often associated with sepsis, including pneumonia and staph. People who are older are more likely to develop sepsis and to die from it. Even if someone survives sepsis, they're not out of the woods. Post-sepsis syndrome is also real concern, Standiford said. People can be depressed, anxious, and can be more likely to get a new infection. "They can get what looks like post-traumatic stress syndrome," he said. "Some people think that sepsis has reprogrammed the immune system to make them more susceptible to new diseases in the future."

Sepsis is tricky to treat and research in part because it looks different in everyone, Standiford said. Different people's immune systems could react differently to the same thing for a variety of reasons, including age. To treat sepsis, doctors cannot consider the illness alone; they also need information about the patient.

"Being able to precisely assess the immune response in an individual patient is a very important area of research that I think a lot of people are interested in," he said. And understanding that response would be key to choosing a treatment—whether that treatment was originally a cancer drug or not.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Kate Sheridan is a science writer. She's previously written for STAT, Hakai Magazine, the Montreal Gazette, and other digital and ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.