Updated | I am sitting on a white beach as the sun sets over the Gulf of Mexico, watching a pod of dolphins play. Groups of wild birds stalk the tide line, eyeing the sand for small invertebrates. The beach stretches away for a mile and a half on either side of me; behind me are a few private houses set among strangler figs and mango trees. This is Captiva Island, home to Robert Rauschenberg, one of the most successful American artists of the 20th century.

Anyone can visit the island, yet staying at Rauschenberg's residence is an opportunity few get to experience. I'm here because the Rauschenberg Foundation has invited me in the run-up to a major retrospective of the artist that begins at Tate Modern in London next month, before moving to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and then to San Francisco.

Robert Rauschenberg, or Bob, as he liked to be called, bought his first place on Captiva, a flat, sandy island 20 miles south of Fort Myers on the western coast of Florida, in 1968. New York was on the verge of financial collapse, and his contemporaries in modern American art were all moving to off-center locations: Jasper Johns to the Caribbean, Sigmar Polke to Afghanistan, Donald Judd to Marfa, Texas. "Something in the 1960s was coming to an end," Achim Borchardt-Hume, the director of exhibitions at Tate Modern, tells me. "Race riots, the death of Bobby Kennedy, the death of Martin Luther King, the death of Janis Joplin…. It was the end of an era of postwar Utopian optimism."

Captiva, beautiful and remote, felt to Rauschenberg like an idyllic alternative. It had "a magic that was unexplainable in its power," the artist noted. He would live on the island for another 38 years, and it remained a profound influence on his art until his death in 2008.

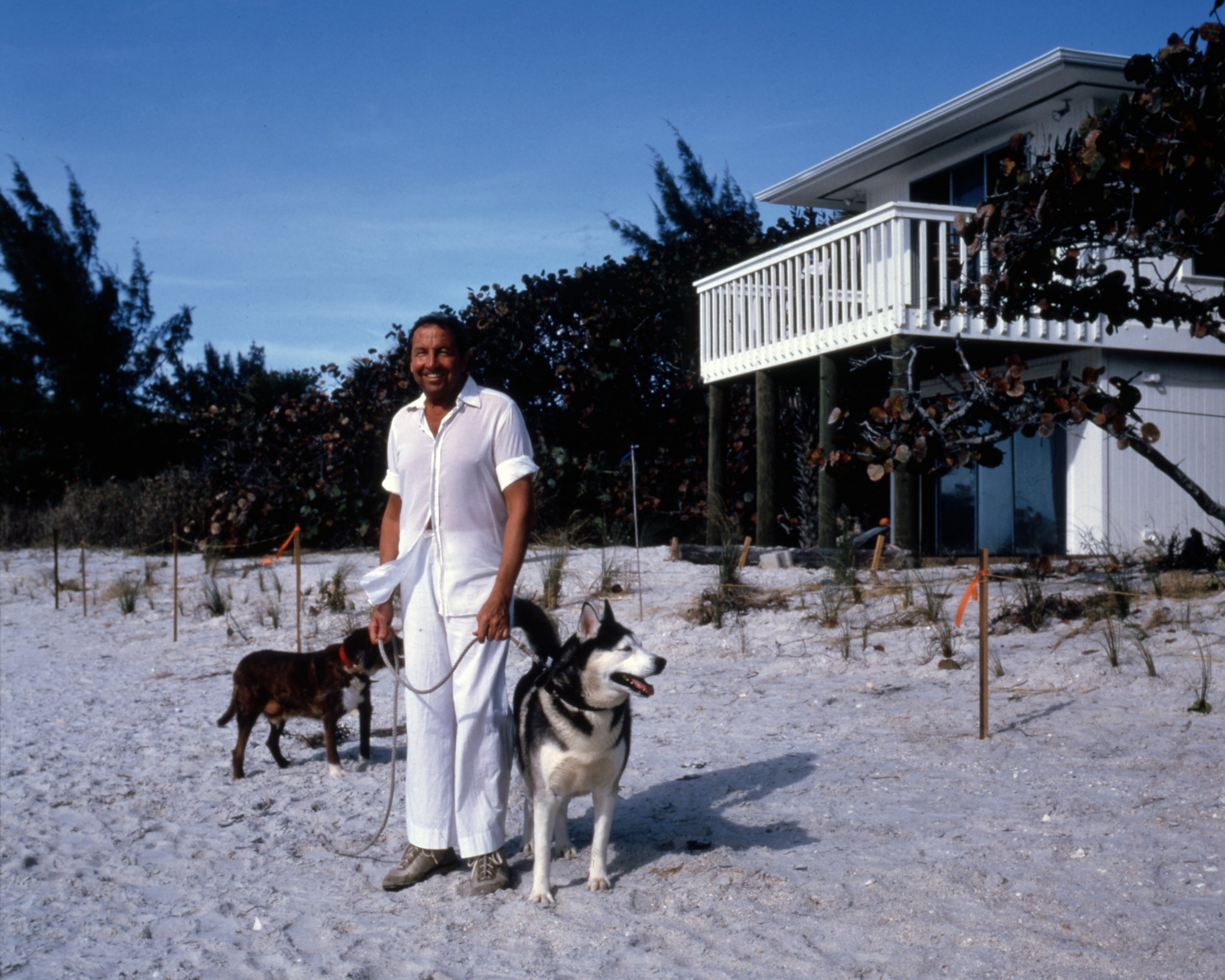

Rauschenberg's first property on Captiva was Beach House, a two-story building on the shore. In 1970, he moved his main base from Lafayette Street in Manhattan to Beach House, building a studio on the ground floor. In the decade that followed, Rauschenberg purchased six more properties, spread across 20 acres, becoming the largest single landowner on the island. His goal was to keep Captiva as untouched as possible.

Why? Because things became simpler there. Rauschenberg had time to expand on his ideas and techniques. His art became softer, with pieces printed on fabric and works made from found cardboard. He created experimental pieces such as the Gluts series: wall sculptures pinned and soldered together from pieces of old cars and corrugated iron sheets (many of these will be in the Tate retrospective). He purchased cutting-edge printing equipment and had space for a huge archive of photographic imagery. The island transformed his work.

American Pastoral

Today, you reach Captiva via a single road coming off the slightly larger neighboring island, Sanibel. It's only a mile and half wide and 4 miles long, and just 379 people live here year-round; the majority of the houses are holiday rentals, let to eager Americans drawn to the island's white beaches and wildlife reserve. It's bounded to the east by Pine Island Sound, where a freshwater river empties out from Fort Myers. A mere 10-minute walk to the west is the Gulf of Mexico. Rauschenberg's property is set between the two coasts.

Nomadic tribes settled the island 12,000 years ago. Spanish pirate José "Gasparilla" Gaspar named it Captiva in the 18th century and used it as a place to imprison women he had kidnapped from wealthy families for ransom. By the beginning of the 20th century, it was a small farming and fishing community; its only notable resident after Gaspar was the Pulitzer Prize–winning satirist "Ding" Darling, who settled on Captiva in 1935 and helped establish a wildlife reserve that covers 6,300 acres and is home to more than 300 species of birds, 30 kinds of mammals and 50 types of reptiles.

Darling's home, the Fish House, is the gem in Rauschenberg's property. A one-story, early 20th-century white-wood slice of Americana, it stands in the middle of the water at the end of a wooden jetty, looking like something straight out of a Herb Ritts photograph. (Ritts did in fact shoot here, while visiting his friend Rauschenberg.) Each building, though, has its own vibe. The Waldo House is a tiny Native American plantation worker's home from the 1920s, while Rauschenberg's final addition to the property is a huge bunker-like studio he built in 1993. The artist's presence is everywhere—from his books, which line the shelves in each of the houses, to the studio equipment, much of which he used. The walls are decorated with Rauschenberg's own prints, and each house is modestly furnished with Rauschenberg's own furniture. He loved simplicity, and the antique wood tables and midcentury chairs offer a sense of space and calm. It's easy to see why he was so immensely productive here—when not fishing or walking his six dogs.

Fishing and walking are about the sum of it: There are few commercial enterprises on the island, save a small library, Jenson's marina, some pink-painted gift shops, and a handful of delis and restaurants. (Rauschenberg's favorite was the Mucky Duck, a seafood place on the beach.) The flora and fauna are what make Captiva so special. Five different types of dolphins swim in its waters. Mango trees come in three colors—white, black and red—and Spanish moss hangs like dirty washing from the branches of the twisted strangler figs. When a particularly bad hurricane season in 2004 flattened many of the figs, Rauschenberg's first thought was to replant. More than a decade later, parts of his property are as dense as a century-old forest. One of the most recognizable trees on the island is the sea grape, with large rounded leaves that turns deep orange and purple in the autumn. Their berries fall, ferment and are eaten by birds, which stumble around drunk, their beaks stained purple.

By the time of Rauschenberg's death, his properties at Captiva housed a huge archive of his art, much of it filled with the sense of energy and productive freedom that came from being on the island. The Robert Rauschenberg Foundation, formed to support the causes he cared about, has continued that tradition, establishing a very successful artist residency program at Captiva. This has a strong focus on climate change—according to the foundation, a third of Captiva is expected to be under water in seven years' time. "Artists can change the world," says the director of the residency program, Ann Brady. "We give them five weeks to do it!"

Artists may or may not change the world, but Borchardt-Hume says the Tate's retrospective, four years in the making, will be "a story about how art and artists relate to a changing world." Rauschenberg is an artist who not only drove the aesthetic changes of modern art; he also reflected and responded to the human landscape—as well as the landscape of a small, flat, sandy island off the coast of Florida.

The Rauschenberg Residency is closed to the public, but group and individual tours are occasionally arranged on a case-by-case basis. "Robert Rauschenberg" is at the Tate Modern, London, from December 1 to April 2.

This article has been updated to state that Rauschenberg would live on Captiva for another 38 years, not 28, and that he purchased six properties spread across 20 acres, not 22.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.