The presidential election has been viewed as a litmus test for how Americans think about the economy. To generalize, coastal urbanites think things are going more or less OK and rewarded Hillary Clinton, while Rust Belt and rural Americans viscerally feel the economy's unfairness and voted for Donald Trump. But unfortunately, both major-party candidates have failed in diagnosing the main source of the nation's economic problems, and it can be summed up in one word: technology.

When we've seen three decades of well-paying manufacturing jobs replaced by low-paying service-sector jobs with little or no benefits, and when vast stretches of America's industrial infrastructure have turned into decaying ghosts of prosperity past, it shouldn't be any surprise that a lot of Americans—on both right and left—are unhappy with the status quo. Many felt no choice but to vote for a person who was not the status-quo candidate.

With the country as deeply divided as it has been in living memory, President-Elect Trump's mandate, what there is of it, seems to be to rescue U.S. jobs held captive by pesky foreigners and greedy "offshoring" industrialists who have turned the deserving American into economic road-kill; thus the dissing of global trade deals like NAFTA and the now-utterly-dead Trans Pacific Partnership.

There's just one problem with that reading of the economy: it's a lie. To suggest that trade deals are the main cause of the massive economic dislocation and historical concentration of wealth that have justly enraged so many Americans is to ignore the much vaster impact of technological change. The question is whether both candidates were simply afraid to publicly acknowledge it or if they just don't understand.

In a recent interview with the BBC, Michael Hicks, an economics professor and director of business research at Ball State University in Indiana, explained how the jobs were lost: "The US has lost…some 7.5 million manufacturing jobs since the late '70s, two-thirds of those in the past decade and a half, but the evidence that those have gone to workers in China, Mexico or Vietnam is pretty small. Our study said 88 percent of those job losses were due to machines, another 12 percent due to offshoring. There are a number of studies on this, but the academic debate is between 80 and 90 percent."

Hicks flat-out refutes the understandable but mistaken view held by Americans living in decimated communities that their jobs have gone abroad. He noted that the U.S. had a "record year in manufacturing production," guessing that, "most of the labor-saving automation that we see now is a trend that is going to continue indefinitely."

In other words, if your town has lost a factory, it's not because "we don't make stuff." U.S. companies make and sell more than ever. Chances are nine in 10 you haven't been replaced by another human in another country who got your job courtesy of an ill-considered trade deal that sold American workers down the river. Instead, your job is now done by a robot or a piece of software, and neither Republicans nor Democrats have a plan to bring back the jobs that technology has caused to evaporate more completely than morning dew in a Phoenix summer.

One suspects the reason the candidates didn't make a peep during their three debates about the real reasons for the disappearance of well-paying manufacturing jobs is that they would then be forced to take a hard look at what an incredibly uneven blessing technology has proven to be for U.S. workers. Poking that nest might curtail political donations from Silicon Valley, which now outstrip, by two to one, those from the Wall Street bankers Americans love to hate. And if that conversation started, an even more difficult one would have to follow, which is whether citizens should continue to unquestioningly embrace technology-fueled change, knowing it will prove even more disruptive to our economy and accelerate the massive transfer of wealth to tech elites who already have too much money for their own good (if San Francisco's real estate prices are any guide).

Self-driving cars are an excellent case study. Google, Tesla, Uber, and the U.S. Department of Transportation all laud autonomous vehicles as the wave of the future, noting that as many as 30,000 lives now lost in accidents could be saved every year.

Pointedly absent from the discussion are the approximately 3.5 million Americans that depend on driving for some or all of their income. If those jobs disappear, unemployment goes up more than 2 percent. As Brad Pitt's character gloomily pointed out in The Big Short, "For every one percent the unemployment rate goes up, 40,000 people die."

So yes, self-driving cars will definitely save some lives…but we will also lose others among the millions of Americans kicked to the curb. The money that was fueling a diverse economy will instead be diverted into the very narrow but deep channel that is sucking up more and more wealth in the US: the pockets of tech billionaires.

Autonomous vehicles are just one application of the emerging field of artificial intelligence, and while the transition away from human drivers may take some years, simultaneous effects across the economy may add up to a wave of unemployment that will leave no one untouched. We may very well see further employment declines in manufacturing because of 3D printing, healthcare because of algorithmic diagnostics, accounting because of software, and on and on ad nauseam. There is now even code-writing code, which will eventually put even the high priests of the technological reformation themselves out of work.

It's not merely technophobes who recognize this. MIT's Erik Brynjolfsson, co-author of The Second Machine Age, has been writing about this issue for several years. In a TED talk, he explains, "We have created more wealth in the past decade than ever, but for a majority of Americans, their income has fallen. This is the great decoupling of productivity from employment, of wealth from work." Brynjolfsson explains better than most that we really can't fully grasp the exponential—and wholly unprecedented—changes that are already rapidly transforming our economy. Yet, at odds with the evidence in his own book, he's still confident that somehow it will all work out. Maybe for esteemed professors whose jobs are not (currently) in danger, rolling the dice seems fine. But the truth is, when it comes to what the potential job losses might be, nobody, including Brynjolfsson, truly knows, because there has never, ever been a moment like this in human history.

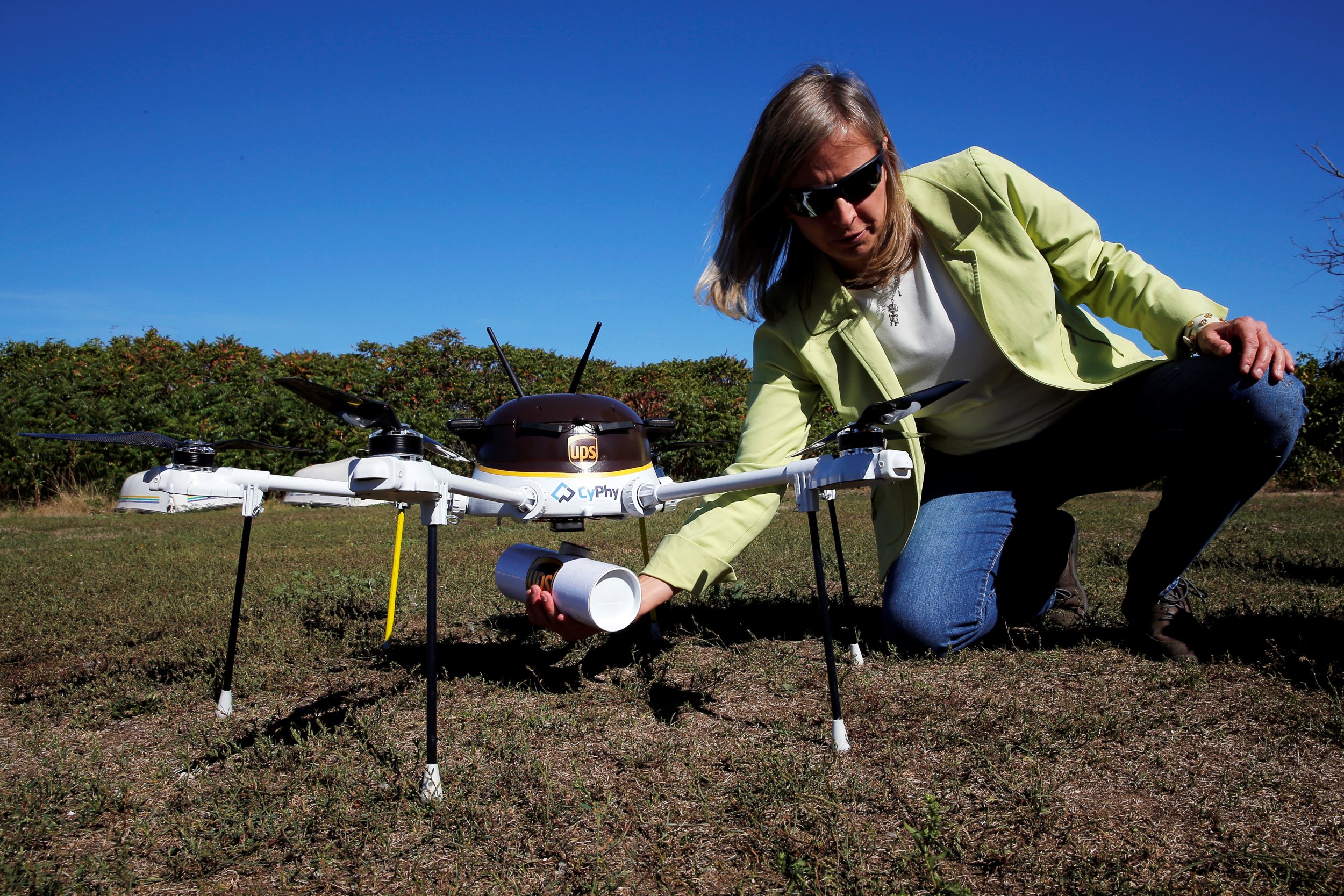

As more and more of our economy is transformed into information, and as the rate of information processing speeds exponentially, technological change and its impact is accelerating. While it may not be completely halted, our political classes and technologists themselves have to start asking hard questions now about whether their techno-utopian ideology is more important than the many Americans it hurts along the way. Could valuing people and offering them a role, a sense of purpose, and employment—rather than, say, a reason to riot in the streets—possibly be a higher goal than robotic healthcare, self-driving cars and drone delivery services?

It's time to start the first real discussion about how to have a sustainable relationship with technology. This discussion needs to happen before this tsunami of technology slams into our economy. It needs to be far more skeptical about the benefits and sensitive to the drawbacks of technological change than it has been. Because if we don't ponder these rapid shocks to our fragile economy now, a great many of us—including plenty of white-collar, high-tech workers—will have all too much time to ponder it a few years down the road.

Art Keller is an ongoing contributor to The Technoskeptic. His work has appeared in a wide variety of leading media outlets including Forbes, Newsweek, The New York Times, The Washington Post, Foreign Policy, CNN, CBS, PBS and the BBC.

The Technoskeptic is a magazine taking a critical look at the impact of technology on society with original reporting, analysis, a podcast and events. Visit them online at TheTechnoskeptic.com.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.