On Saturdays outside my Brooklyn apartment, you can buy used cassette tapes from an older couple who set up shop each week with a modest tag sale. The tapes are dusty and cost $1, though on Amazon they would not be worth the cash it costs to ship them. Last week's selections included Depeche Mode's Speak & Spell, k.d. lang and The Reclines' Absolute Torch and Twang, and King Diamond's Conspiracy. I looked but didn't touch. Though I'm fairly omnivorous in my purchasing habits—I regularly collect used CDs for the cheap physical gratification, vinyl for the audiophile urge, and MP3s out of necessity—I haven't sought out a pocket-sized cassette since I misplaced an Everclear tape in fifth grade. I replaced that one with the CD and never looked back.

Or you can take the L Train four stops west, trek towards the river, and enter Williamsburg's lavish Rough Trade record store, where a small rack entirely devoted to the compact cassette sits near the center. These are newer and altogether hipper selections and though they cost about half as much as an LP there, they aren't exactly bargains. The Black Angels' debut Passover will run you $13.99, while Woods' recent With Light and With Love costs $10.99 and EMA's The Future Void is listed at $9.99. On a good day, 10 tapes make it to the cash register. That's a tiny fraction of Rough Trade vinyl and CD sales, though store manager Hope Silverman says it's growing.

"I was a skeptic, too, in the beginning," Silverman says. "I was like, Oh gosh, should we carry these? And then I started to see [labels] were putting all these things out and I got tempted into it." Since then, new releases by rapper Freddie Gibbs and garage-rocker Ty Segall have sold surprisingly well on cassette. "It's still in kind of a formative stage. [But] it's only going to get bigger." So it has at California's famous Amoeba Records, which has locations in Berkeley, San Francisco and Hollywood. "I don't think we've ever had a day where we've sold less than 100 cassettes at each of our stores," says founder Marc Weinstein, who told Newsweek he's seen sales pick up substantially over the past year or two.

Weinstein credits that rise to the romance of the personal mixtape and fondness for "a simpler time that cassettes represent." This weekend could be a proving ground for that romance. On Saturday, Amoeba and Rough Trade joins more than 100 U.S. retailers participating in the second annual Cassette Store Day, a Record Store Day spinoff wherein fans flock to nearby stores to collect limited edition releases readymade for your 1979 proto-Walkman. Among those treasures is an early edition of the new album by indie duo Foxygen, which won't be out on CD or vinyl for another two weeks. Silverman and coworker Emmy Feldman, meanwhile, started a label to release recordings of their own on Cassette Store Day.

Can the momentum last? Though the annual celebration was launched in Europe in 2013, the stateside observance is now organized by Sean Borhman, founder of the California record label and store Burger Records, which claims to have sold between 300,000 and 350,000 cassettes since its founding in 2007. "When we started making cassettes, no distributors were making cassettes. None of the new albums coming out were on cassette," Bohrman recalls. Now, "we're being hit up by Weezer to put out their tape." He adds, "We kind of helped the format come back into popular culture."

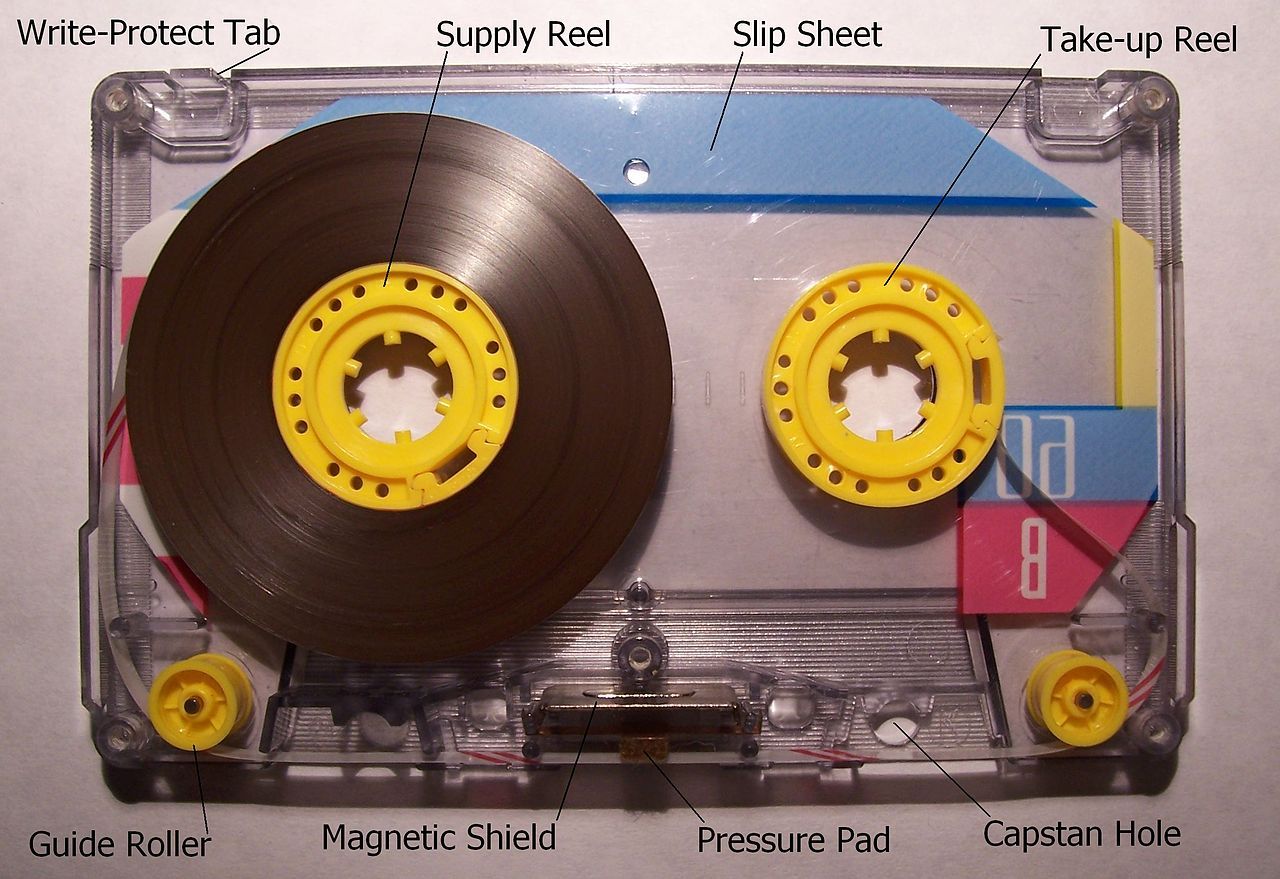

Here's the tricky thing: in small but significant corners, the format never left. Decades past its commercial prime, the sad little cassette, with its tiny-font labels and twisting tapes, has remained popular in punk and noise communities. That makes sense. The cheap manufacturing costs mesh well with DIY ethics, while tinny sound quality isn't such a barrier for hardcore music that thrives on low production values and high compression.

"They're a really big symbol of being able to do things your own way," says Kevin Greenspon, who runs Bridgetown Records and releases his own music on cassette. "If I need to make 50 more for the next string of shows, I can do that at home." In cassette-world, you only need a 4-track and blank tape to make (and distribute) a record.

But as Cassette Store Day highlights the tape's resurgence on a somewhat broader scale, labels and stores are playing catch-up. "Cassette Tapes Are Almost Cool Again," heralded a post on VICE's Motherboard blog last summer. The Brooklyn-based Partisan Records, for instance, has come to view them as collector's items. When the label issued a small number of cassettes for psych-rock band The Wytches to sell while on tour, Partisan's owners noticed them popping up on eBay at a higher price.

To be clear, these modest sales aren't exactly poised to save the music business, and industry analysts are duly skeptical. Pop-chart columnist Christopher Molanphy says his weekly Soundscan data doesn't include breakdowns by format but warns that talk about resurging sales for analog mediums, including vinyl, is often "wildly overblown." He adds, "The percentage increases tell you little about the miniscule absolute numbers these formats are selling." As chart columnist Paul Grein pointed out in a Yahoo piece last year, no cassette has sold 50,000 copies in a single year since The Wiggles' Yummy Yummy in 2004.

But at a surreal moment where Urban Outfitters is the world's top vinyl retailer and Apple claims the largest album release in history, why wouldn't labels explore the market? Nostalgia's a potent drug, and the music industry has changed abruptly enough that even twenty-somethings like me feel wistful for the lost '90s. Though I'm not yet 30, I can recall my very first cassette (Red Hot Chili Peppers' much-maligned One Hot Minute) far more easily than I can name my first CD or MP3 or Spotify stream.

Ironically, the Internet now plays a role in supporting the cassette boom rather than shuttering it. Zully Adler, who runs a small label called Goaty Tapes and several years ago won a Watson Fellowship to explore cassette culture around the world, says the web has facilitated the rise of online tape networks everywhere. "You get this kind of palimpsest of different communities," Adler says. "This is kind of the funny thing about Cassette Store Day: the only way I can sell a hundred copies of a tape is through my website."

Plus, for experimental musicians, lo-fi techniques are often a welcome respite from the harsh digital sheen that swallows modern recordings. As Brooklyn musician Ben Seretan explains it, "A zoom recorder or someone's mic built into their computer sounds 'sharp' and 'digital' to me. But with a cassette deck you can kind of just throw it on and the magic world emerges naturally."

"Tape has the effect of rendering things more mysterious," Seretan adds. "More bleary. More unearthly. In short, more beautiful."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zach Schonfeld is a senior writer for Newsweek, where he covers culture for the print magazine. Previously, he was an ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.