The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) announced Wednesday that there is sufficient evidence to prove the Zika virus can cause microcephaly and other birth defects. Using established scientific criteria, the authors reviewed existing data and studies and concludes the link between the mosquito-borne illness and infant brain defects should no longer be considered speculation.

The findings of its analysis, which included more than 40 relevant studies, were published April 13 in The New England Journal of Medicine. The authors say common threads in existing studies and isolated cases, along with the absence of an alternative explanation, confirms the link.

"This study marks a turning point in the Zika outbreak," Dr. Tom Frieden, director of the CDC, said in a press statement. "It is now clear that the virus causes microcephaly. We are also launching further studies to determine whether children who have microcephaly born to mothers infected by the Zika virus is the tip of the iceberg of what we could see in damaging effects on the brain and other developmental problems."

He added that these findings affirm the CDC's existing guidance for women who are pregnant or wish to conceive to avoid travel to countries affected by the outbreak. " We are working to do everything possible to protect the American public," Frieden said.

Since the current outbreak began a little more than a year ago, at least 4,000 infants in Brazil have been born with microcephaly, a birth defect in which a baby has an abnormally small skull and incomplete brain development. Researchers also reported a smaller cluster of Zika-linked microcephaly with eight confirmed cases during an outbreak in French Polynesia that occurred between 2013 and 2014.

In early February, the World Health Organization declared Zika-related microcephaly a "public health emergency of international concern" and urged a global coordinated response to improve surveillance of Zika infections and congenital defects that occur in countries with outbreaks.

Researchers have been unable to confirm the link in a single study; nearly all have limitations even recognized by their researchers, which include small sample sizes and lack of control groups.

In the analysis, the authors recognize a consistent set of features in congenital Zika infections including severe microcephaly; brain calcifications and other abnormalities; certain eye defects that could threaten vision; redundant skin on the scalp; arthrogryposis (curvature of the joints); and clubfoot. Zika infections in pregnant women also have been linked to miscarriages and stillbirth.

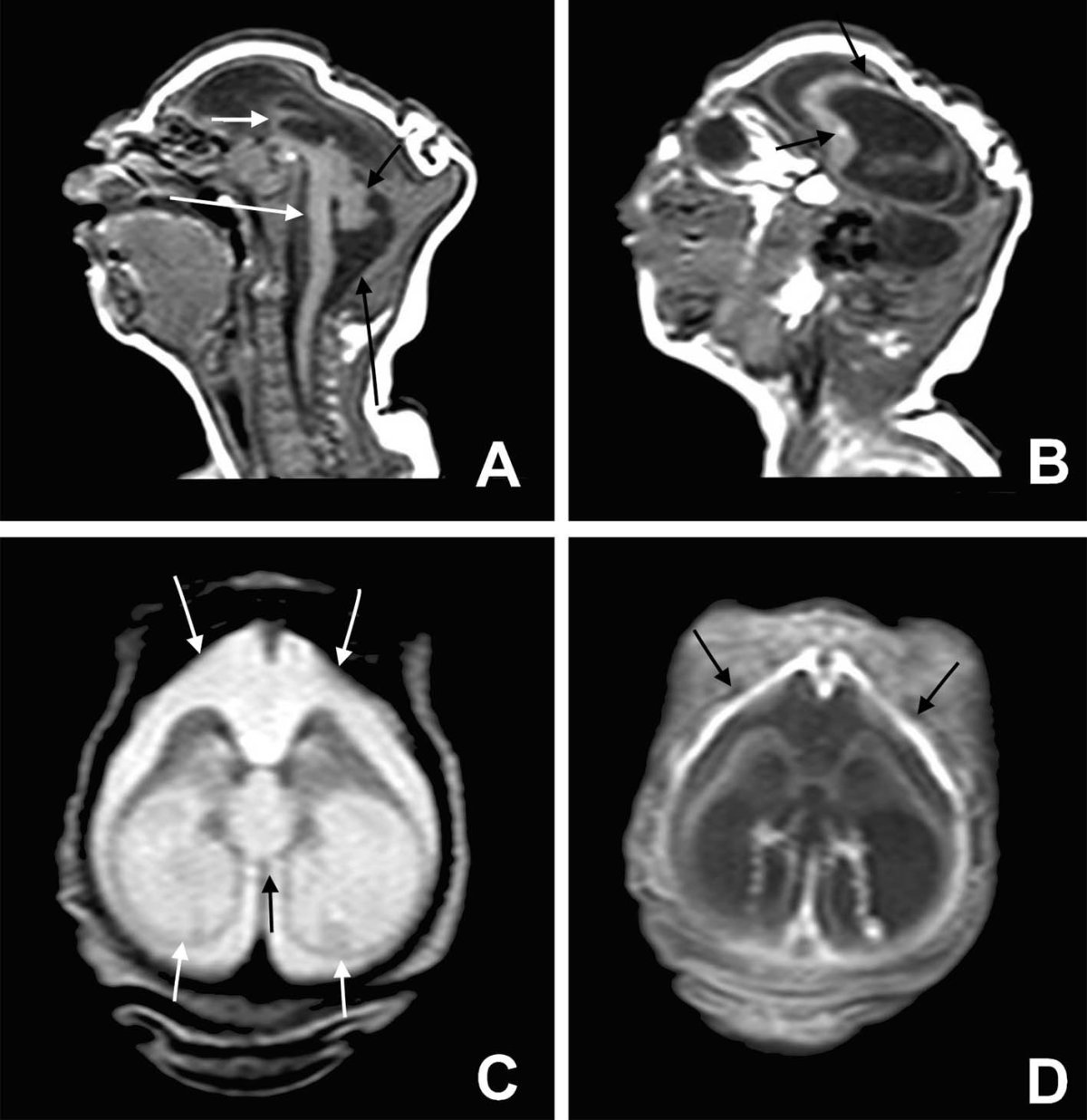

A new paper in BMJ, also published April 13, describes these congenital abnormalities in greater detail. A group of researchers conducted exams on 23 infants born with microcephaly infections in Pernambuco, Brazil between July and December 2015. Of the cohort, 15 underwent CT scans, seven underwent both MRI and CT scans and one of the infants only underwent an MRI. After analyzing the medical imaging, the researchers described the majority of the brain damage in the infants as "extremely severe."

All but one of the mothers reported rash during pregnancy, and tested positive for the Zika virus. Six of the infants tested positive for Zika antibodies, while the remaining 17 met the clinical protocol for microcephaly. Through blood tests, the researchers ruled out other possible causes for birth defects, including toxoplasmosis, cytomegalovirus, rubella, syphilis and HIV.

In CT scans of infants, they identified calcifications in brain tissue. Scientists have suspected for some time that the Zika virus kills brain cells, which causes lesions, or scars, to the brain that leave calcium deposits. The infants were also found to have underdeveloped cerebellums—responsible for motor control—and brainstems, which connects the brain to the spine.

Some of the infants also had malformations to the outer (cortical) area of the brain, as well as decreased brain volume and enlarged brain cavities. The scans also suggested delayed myelination in the infants. Myelin sheaths form around nerves and they're essential to facilitating communication between the brain's two hemispheres. While this was an observational study, it is in line with findings from other case studies on congenital Zika infections. The authors come to a similar conclusion as the CDC: Microcephaly is just but one feature in what many are now clinically describing as Zika virus congenital syndrome.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Jessica Firger is a staff writer at Newsweek, where she covers all things health. She previously worked as a health editor ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.